Labyrinth

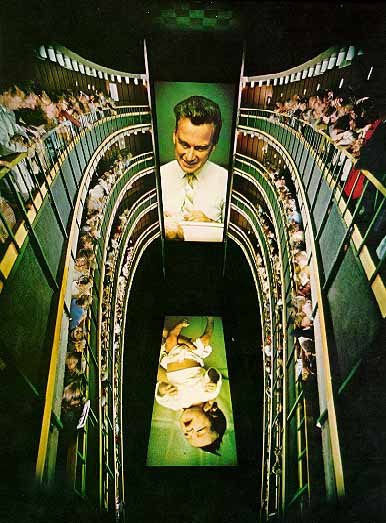

Perhaps the most important film project at Expo was Labyrinth. Roman Kroitor, who directed it, and his associates at the National Film Board were assigned by Expo to produce a cinematic experience that would illustrate the theme of Man the Hero. They arrived at the idea of a labyrinth, into which by ancient tradition, the hero would enter in order to find and kill the dreaded man-eating Minotaur at its center. To make the myth contemporary, the film makers developed a new kind of walk-through cinema and they shot film throughout the world. And to show it they built a five-story building and filled it with three chambers. They attempted to show that modern man, too, finds himself entangled in a labyrinth. The monster he has to face is himself - this inner struggle is the one which will enable man to triumph over his own hesitations.The hero entering the labyrinth this time was Man - essentially the audience. People were led in near darkness along a maze of ramps where they emerged at one of four vertically stacked elliptically- shaped balconies. There they could view the film on a vertical screen to the side of them nearly 50 feet high, and if they leaned over the railings also on the screen below. The images were connected so there were always two ways at looking at things.

| The windowless Labyrinth building was mysterious from its exterior. |

The movie began on the screen below with a baby being born in a hospital. The doctor grasped the baby with its umbilical cord still attached to its mother and held it up - it appeared on the vertical screen. Then the baby became a child, climbing a construction site. The building went up the vertical screen and the ground was far below on the floor screen. Soon he was a teenager on a motorcycle and in the water. He encountered difficulties - an accident, then a riot. He discovered that life had moments of victory as well as moments of defeat.

|

Viewers watched the multi-screen cinema from a series of tiered balconies. |

As the scenes faded the visitors were led into a second chamber, a dark mirrored maze. Dark winding corridors, full of blinking lights and sounds lead to another auditorium where five screens were used at the same time to show different scenes arranged in a cross. The visitor sat down and watched images that were concerned with the fate of the hero and his struggle with the beast. There was one memorable five-screen scene where a determined yet frightened Ethiopian in a dugout canoe paddled up to a crocodile and killed it with a spear thrust. At the moment the crocodile screamed, the central screen was filled with its writhing body while the four screens around it lit up with frightening still-photos of African masks. However, the last theater was more concerned with getting across the point of the Labyrinth - the beast isn't really a crocodile but something within us. The struggle was then to face oneself.

The scenes shifted to a family breaking up as its young people moved to North America. There were images of transition and of death and towards the end a view of the ancient Angor Wat temple overgrown by a gigantic tree. When the lights came on, people's faces were frozen in wonderment, not quite comprehending what they saw, but lost in the act of self-examination.

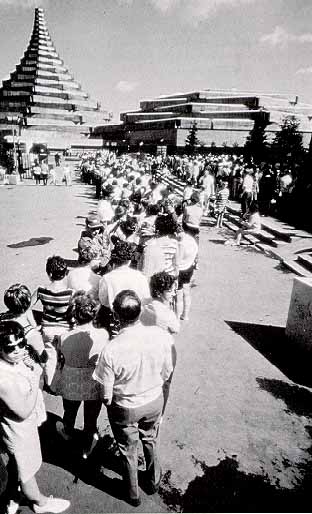

The lines for this movie were often two, three, even four hours long. And as those who exited the Labyrinth often came up to those waiting patiently in line and reassured them that the wait was worth it. The night that I saw the film, my parents and I waited nearly two hours in line. Young people enjoyed the movie more than older people who were often somber after thinking about their advancing age. Children found the movie confusing, yet hardly anyone really understood what it was all about.

|

The lines for the Labyrinth pavilion were often 2, 3 and sometimes 4 hours long. People, who had just seen it, often came over to people in line to reassure them that it was worth waiting for. |