Habitat 67

Habitat 67, an experiment in apartment living, became the permanent symbol of Expo 67 after it closed. It was Canadian architect Moshe Safdie's experiment to make a fundamentally better and cheaper housing for the masses. He attempted to make a revolution in the way homes were built - by the industrialization of the building process; essentially factory mass production. He felt that it was more efficient to make buildings in factories and deliver them prefabricated to the site. |

Habitat's 158 living units resembled a Taos Indian pueblo. |

Safdie was dissatisfied with both suburbia, which destroyed open space surrounding cities and cut off people's enjoyment of the amenities of city life, and with the high-rise apartment block, which concentrated people on less land. Apartments generally were too small for growing families, and lacked both privacy and outdoor space. He was convinced the later were inadequate as family housing.

He planned Habitat with the goal to find a way to put a great many people on a small space, yet provide them with at least some of the pleasures of a private home. He wanted to build a city in the sky, a 3- D city and his city would contain 1000 housing units, with shops and even a school. What he proposed was an experiment, not just in housing, but in community life.

But between 1964 and 1966 when construction started, it was downsized to only 158 dwelling units, without shops and a school. What started out as a plan for a small city, instead became a hugely expensive apartment building. Worse, while it was on Expo 67 grounds, when Expo 67 closed, it would be some distance from the rest of Montreal's business and housing neighborhoods.

As Habitat was designed, it resembled a curious concrete mountain of dwelling places, strikingly modern, yet reminiscent of a Taos Indian pueblo village, or an Italian hill town. Its units were built on the ground, then hoisted by crane into place five, six or more stories above the ground.

|

View of Habitat 67 shows what appears to be random stacking, but

actually one unit's roof was another's rooftop garden. Photo by Bill Dutfield. |

A factory was built beside the Habitat site. It contained four large molds in which the standardized units were made. To make each of them, a reinforcing steel cage was placed inside the mold, then concrete was poured around the cage. After the concrete cured, the unit was moved to an assembly line where a wooden sub-floor was installed with electrical and mechanical services below it. Windows and insulation were then inserted; afterwards prefabricated bathrooms and kitchen modules. Finally the unit was moved to its position in the building.

|

After concrete units were cast they were moved with this crane. Photo by Bill Dutfield. |

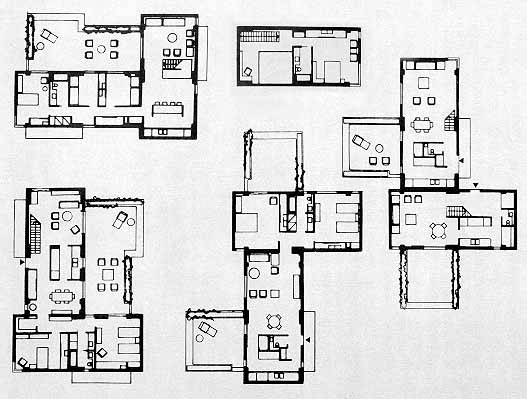

There were 354 of these units in all. But it was the way they were put together than produced the variety of forms that made Habitat, both inside and outside, so unusual. The units were arranged to provide fifteen different types of "houses". These varied from one-bedroom houses (600 sq. feet) to four-bedroom houses (1,700 sq. feet). Each had a private open garden space, 37 x 17 feet. Each man's roof was another man's garden. The arrangement of the units provided privacy and the variation in house layouts provides a sense of uniqueness.

|

Some of the various floor plans available. |

While factory production techniques should have cut overall costs, building 158 apartments isn't really productive in factory work since there is often a steep learning curve. Also since the individual units would bear the weight load of the units above, the units on the bottom where actually thicker and stronger. In the end Habitat 67 cost $22,195,920, or about $140,000 per living unit. Effectively that was the same cost as building six-eight ordinary town houses. Luckily one could rationalize that it was only a prototype, and if scaled up, it might be much cheaper to construct.

|

An aerial view of Habitat 67 shows that one unit's roof was another's rooftop garden. |

While the visiting public was impressed, they didn't embrace the concept. At a distance the complex looked like an exciting piece of Cubist sculpture, at close up it's flat concrete-gray exterior looked boring and as if nobody lived there. Inside the complex Safdie's plastic covered pedestrian streets, connecting the apartments with the elevators and parking lots, were poorly sheltered from Montreal's cold window weather. Perhaps if it had been built near one of Montreal's exciting neighborhoods, the public might have been more willing to accept it, but then few of Expo's fifty million visitors would have seen the innovative housing site.

|

View of Habitat 67. Photo by Bill Dutfield. |