Experimental Multi-Screen Cinema

The pavilions at Expo 67 showcased hundreds of films and slide shows, but the only one that were memorable were those that used more than one screen. Certainly it wasn't the first time that film makers tried multi-screen cinema at a world's fair. The three screen film "To Be Alive" was the hit of the 1964 New York World's Fair, and their were others at Brussels in 1958 and at Paris even earlier. But Expo gave the viewer a new way of seeing. If two images were projected side by side on the screen, the eye compares and combines the two images, and the mind interprets them freshly, greater than their two parts. Expo cinema forced the viewer to look at various subjects in a new light. It stretched viewer's visual imagination and made them participate in the visual experience rather than just absorb it.

CANADA 67 - The Telephone Pavilion

The most popular film at Expo 67 was "Canada 67" that was commissioned by the Canadian telephone companies. The 22 minute film was executed in Circle-Vision 360 degree, a total wrap-around process where 1500 people stood in a room surrounded by nine large movie screens. Nine projectors, concealed in the space between screens, projected a completely circular image while twelve synchronized sound channels enveloped the audience in sound. The film was made by the Walt Disney Studios with a nine-camera rig weighing 400 pounds. |

Caption |

Although it was difficult to see more than half of what was shown at any one time, the effect was magical, especially when the camera was in motion in a plane, on a boat or on a railroad train. There was a scene while flying above Niagara Falls. When the plane banked to keep the falls in view, people gasped and reached for the railings to keep from falling.

"Canada 67" was the most nationalistic film at Expo and it celebrated every Canadian symbol imaginable. It began on the east coast with the Canadian Mounted Police lined up in a circle, lances pointed and charging. The camera traveled west by various modes of transport, visiting Quebec City's Winter Carnival, a Toronto Maple Leaf's hockey game, then traveling west across lakes and prairie farm country to wide open wilderness, and Canada's National Parks. The action at the Calgary Stampede was exhilarating and the finale naturally was "O Canada."

A TIME TO PLAY - United States Pavilion

Art Kane, "A Time to Play's director, set out to make a film about children's games. The twenty minute film was shown on three screens set side by side. While the racially balanced group of children were obviously over rehearsed to the point that they lacked spontaneity, it did convey the intensity and earnestness in which they played their games.The children played games like "King of the Mountain" that are a good preparation for the grown up adult world that they would soon face. In the game "Hide-and-Seek, Kane used the three screens effectively. The seeker was on one screen, a child hiding on another. And sometimes he merged all three screens into one as in the game "Tug- of-war." But in the end, despite awkward acting, Kane did succeed in portraying more of the real world of childhood than most "charming" films ever do.

WE ARE YOUNG - C.P.R. Cominco Pavilion

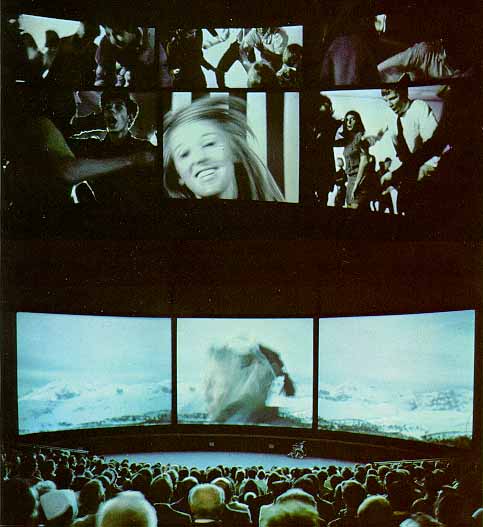

Francis Thompson and Alexander Hammid who previously won an academy award for their 1964-1965 World's Fair three-screen movie "To Be Alive," made a more ambitious film for C.P.R. Cominco. The subject this time was about young people, teenagers who faced life, and they used six screens to present their subject. In a sense they were successful in drawing a convincing performance from several hundred amateur actors.They began with an exuberant sequence of teenagers at play - dancing to rock bands and riding motorcycles. They showed children riding a horse, and a couple of teenagers in a jeep racing with boys on horses across a field. But it was the way the images were presented that made the film memorable. The motorcycle sequence involved a six- screen repetition of the image of a white line on a highway rushing furiously toward the viewer. The teenage dancers were shown spread across six screens so that the viewer could watch them in six different ways; a group of four in one frame, a close-up of a girl in another, a pair in another, etc.

|

The film "We Are Young" was shown on six screens. |

The film makers then followed two young girls who moved to a big city to take jobs. The girls despair at the boredom of their work. In one scene a girl learned to type. Viewers saw her puzzled face on one screen and then around her on five other screens were close-up scenes of her attempts at hunt-and-peck tying. In another scene the girls sit down to watch television, and suddenly the six screens were filled with what they saw, the horror and banality of the world at large. Some of the other girls take part in a peace march. One says, "You tell us that we can't change the world. We think we can." In a way the movie had a positive ending and the word got around that "We Are Young" was an important movie to see.

THE EARTH IS MAN'S HOME - Man the Explorer Complex

While most of the multi-screen films spread their images out horizontally, this movie was stacked vertically and projected on a screen thirteen feet wide and thirty feet high. Viewers with their necks craned upwards sat beneath it in sling chairs.The film's point was man's ability, or inability, to cope with his various environments; deserts, mountains, jungles and cities. The three screens were used to make to make a point. For instance one screen showed food being scraped off a plate into a garbage can, while another showed a child in the last stages of starvation. At other times it was used to create a mood. When showing a small town, the film makers put a quiet street in the middle frame and flowers at the top and bottom. While the film's message was vague with its message being "here is our world - lets do something better with it," the film had style and poetry to make it one of the finest multi-screen movies at Expo.

A PLACE TO STAND - Ontario Pavilion

The film "A Place to Stand" by Christopher Chapman was one of the few multi-image films that didn't require a special equipment or a special theater to show it. All the images went onto one 70 mm strip of film, ninety minutes of images crammed into a movie running seventeen and one half minutes."A Place to Stand" was about Ontario; its industry, farming, city life, culture and sports. While the images weren't remarkable, they were juxtipositioned in forms that were irresistible. For example; during a scene with a harvester working in a wheat field, the screen was split into fifteen rectangles - fourteen showing only close-ups of wheat, the fifteenth a harvester advancing towards the audience. Then the scene of the harvester grew and grew until it filled half the screen and wiped out the close-ups of the wheat. Other scenes like the chaos of Toronto's night life was split into eight irregular hard-edged shapes so that it was like viewing a movie in splinters of a mirror. The movie had no narration or even sub-titles. It used only sound effects, orchestral music, and a song ("A place to stand, a place to grow, Ontari-ari-ario"

Although Ontario had no magnificent scenery, the visual experience was full of sheer energy and helped change the public's image of Ontario. It was cinematic propaganda on a new level.

LABYRINTH

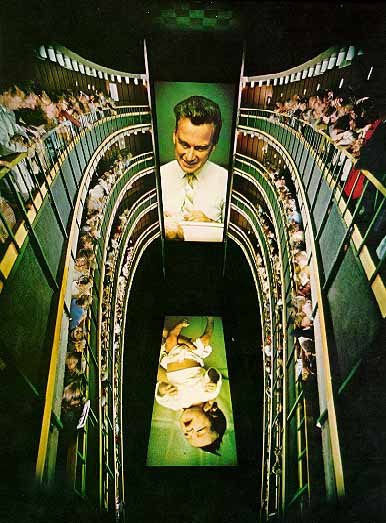

Perhaps the most important film project at Expo was Labyrinth. Roman Kroitor, who directed it, and his associates at the National Film Board were assigned by Expo to produce a cinematic experience that would illustrate the theme of Man the Hero. They arrived at the idea of a labyrinth, into which by ancient tradition, the hero would enter in order to find and kill the dreaded man-eating Minotaur at its center. To make the myth contemporary, the film makers developed a new kind of walk-through cinema and they shot film throughout the world. And to show it they built a five-story building and filled it with three chambers. They attempted to show that modern man, too, finds himself entangled in a labyrinth. The monster he has to face is himself - this inner struggle is the one which will enable man to triumph over his own hesitations.The hero entering the labyrinth this time was Man - essentially the audience. People were led in near darkness along a maze of ramps where they emerged at one of four vertically stacked elliptically- shaped balconies. There they could view the film on a vertical screen to the side of them nearly 50 feet high, and if they leaned over the railings also on the screen below. The images were connected so there were always two ways at looking at things.

|

Viewers watched the multi-screen cinema from a series of tiered balconies. |

The movie began on the screen below with a baby being born in a hospital. The doctor grasped the baby with its umbilical cord still attached to its mother and held it up - it appeared on the vertical screen. Then the baby became a child, climbing a construction site. The building went up the vertical screen and the ground was far below on the floor screen. Soon he was a teenager on a motorcycle and in the water. He encountered difficulties - an accident, then a riot. He discovered that life had moments of victory as well as moments of defeat.

As the scenes faded the visitors were led into a second chamber, a dark mirrored maze. Dark winding corridors, full of blinking lights and sounds lead to another auditorium where five screens were used at the same time to show different scenes arranged in a cross. The visitor sat down and watched images that were concerned with the fate of the hero and his struggle with the beast. There was one memorable five-screen scene where a determined yet frightened Ethiopian in a dugout canoe paddled up to a crocodile and killed it with a spear thrust. At the moment the crocodile screamed, the central screen was filled with its writhing body while the four screens around it lit up with frightening still-photos of African masks. However, the last theater was more concerned with getting across the point of the Labyrinth - the beast isn't really a crocodile but something within us. The struggle was then to face oneself.

The scenes shifted to a family breaking up as its young people moved to North America. There were images of transition and of death and towards the end a view of the ancient Angor Wat temple overgrown by a gigantic tree. When the lights came on, people's faces were frozen in wonderment, not quite comprehending what they saw, but lost in the act of self-examination.

The lines for this movie were often two, three, even four hours long. And as those who exited the Labyrinth often came up to those waiting patiently in line and reassured them that the wait was worth it. The night that I saw the film, my parents and I waited nearly two hours in line. Young people enjoyed the movie more than older people who were often somber after thinking about their advancing age. Children found the movie confusing, yet hardly anyone really understood what it was all about.

POLAR LIFE - Man the Explorer

Film maker Graeme Ferguson made the film Polar Life" for the Man the Explorer theme pavilion. His multi-screen cinema was unusual since the audience sat in four slowing revolving theaters on an enormous turntable with twelve projectors running simultaneously. The audience could usually see two screens but sometimes parts of two additional screens.Although Fergueson used the multi-screen technique in his 18 minute film to his advantage, for instance a man with a tranquilizer gun shooting a polar bear - the man on one screen and the polar bear on the other, what people remembered at the end was the Arctic's stark beauty. He showed beautiful aerial shots of icebergs off Greenland and some of the most stunning shots of the northern lights ever filmed.

KINO-AUTOMAT - Czechoslovakia Pavilion

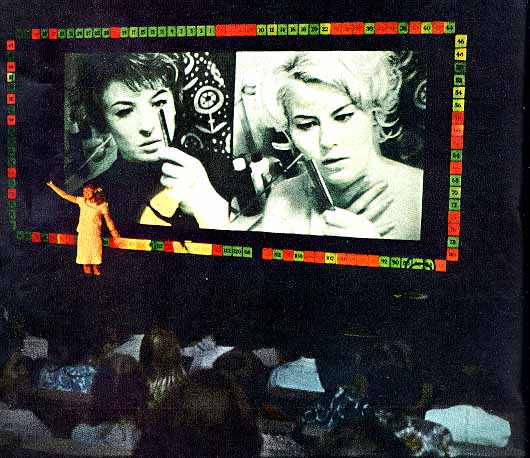

The Kino-Automat film at the Czechoslovakia pavilion was a sociological and psychological experiment with audience participation by just 127 people in an intimate theater. It was developed by cinematographer Raduz Cincera, who reasoned that, just as children like to make Tinkerbell live by applauding during Peter Pan, an adult audience might become involved in a performance with live audiences. Therefore, at five points in the film's plot, the film stopped and the audience was asked to vote on which way Mr. Novak, the hero, should act. Meanwhile, the actor appeared in the theater in person and appealed to the audience to help in solving his problems. Each viewer was asked to either push the red or green button beside him at each decision point. The votes were registered by seat number on a border around the screen, so each viewer could see their own vote counted.

| The Kino-Automat film stopped five times for the audience to vote at various decision points in the story. |

The film began with an apartment building on fire, and immediately the audience was told that Mr. Novak held himself responsible. The actor then took the audience through a series of flashbacks describing the highly unlikely chain of events which brought him through carelessness and stupidity to his conclusion. Although the audience was allowed to dictate some of his choices in the actions with alternative film sequences, no matter what the audience decided, the result was the same - a burning building. Many felt, especially the cinematographer, that it was really a satire on democracy; everyone gets a chance to vote, but voting never changes anything.

Mr. Novak's problem began when, just before his wife was due home, he confronted at the door of his apartment, a beautiful blond woman clad only in a towel. Somehow she had locked herself outside her own nearby apartment. The audience's decision was whether he should let her in. Later when his wife arrived, and misunderstanding everything, ran away, Mr. Novak pursued her in a car. A policeman hailed him down. The audience had to decide whether he should break the law and keep driving. Later in the film, Mr. Novak believed that a young man who could help him lived in a certain apartment. The audience decided whether he should dash in and find the man despite being stopped by an apartment tenant that barred his way. Finally, a porter barred Mr. Novak's way when he was trying to put out what at the time was a minor fire. The audience decided if he should hit the porter over the head and go about his business.

It was a study in group behavior with unexpected results. Audiences always voted for the adventurous course of action, whether it was prudent or not, moral or immoral. A typical audience would vote two to one for letting the blonde in the apartment and four to one for breaking the traffic laws. The audience in over 100 performances, except once, voted for Mr. Novak to hit the porter over the head. The film makers learned that people decided outcomes, not on a moral code but on what they like to see - essentially group fantasy. As an experiment it was great entertainment, perhaps the funniest forty-five minutes at Expo.

POLYVISION: CZECHOSLOVAKIA - THE AUTOMATED COUNTRY - Czechoslovakia

Polyvision presented a panorama of Czech industrial life in an eight minute film that used twenty slide projectors, ten ordinary motion picture screens and five rotating projection screens. While the subjects were all usual industrial operations like hydro-electric power plants, steel rolling mills and textile mills, the visual material was presented in an unusual way. The screens were unconventional in that they would move around; backwards, forwards, even sideways during the show. Then there were other projection surfaces formed by steel hoops that spun around so rapidly that they seemed to from solid spheres and yet they were not solid. One could partially see through the image at what was in the room beyond. The presentation was completely controlled by electronic memory circuits (computer) that controlled the projectors and moved the screens around in a cinematic ballet.DIOPOLYECRAN - Czechoslovakia Pavilion

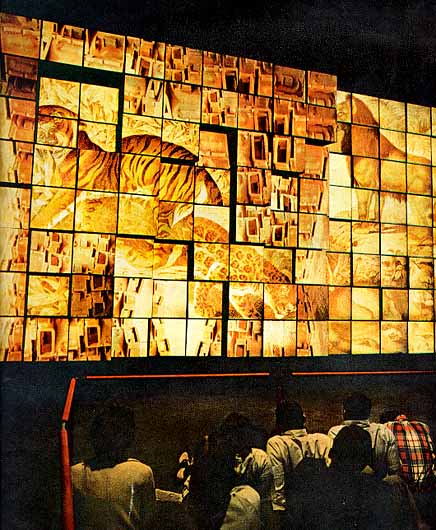

Dioplyecran was one of the most fascinating audio-visual experience that I had personally ever seen. You entered a large room and sat on the carpeted floor where you watched a wall of 112 cubes whose ever shifting and changing images moved backwards and forwards. Inside each cube were two Kodak Carousel slide projectors which projected still photos onto the front of the cubes. In all there were 15,000 slides in the 11 minute show. Since each cube could slide into three separate positions within a two foot range, they gave the effect of a flat surface turning into a three-dimensional surface and back again. It was completely controlled by 240 miles of memory circuitry which was encoded onto a filmstrip with 756,000 separate instructions. |

Viewers watched a wall of 112 projected cubes while seated on the floor. |

The show was about "The Creation of the World of Man." On the 112 part screen, the Earth came awake, flowers bloomed, tigers suddenly appeared, the first men walked the earth, then machinery was invented. Sometimes the image sequences would first appear complete, then be broken up abstractly in a modern art composition. It was pure multi- visual technique than enchanted the viewer. My parents found me 25 minutes later sitting cross-legged on the floor, mesmerized by the images. I had been acting as a scout, entering a pavilion and exiting five minutes later to tell them if the pavilion was worth seeing. Obviously I had found something interesting when I didn't return.