Coney Island - Thompson & Dundy

Revised April 23, 1998

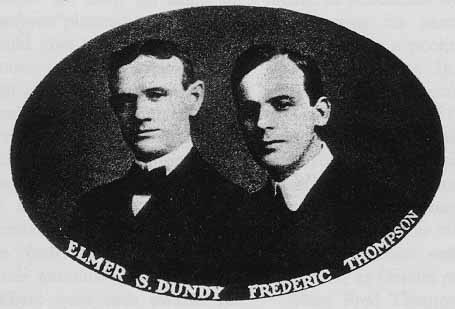

Perhaps of all the showmen that entertained the American public at the turn of the century, none were more famous or successful than the partnership of Frederic Thompson and Elmer "Skip" Dundy. They were best remembered for building Coney Island's Luna Park in 1903 and Manhattan's famous Hippodrome Theater in 1905, but their partnership began even earlier.

|

Frederic Thompson was born in Irontown, Ohio in 1872. He began his career as an office clerk, but since he had natural artistic talent he studied drafting in his uncle's architecture office. At age 17 he quit to start a profitable brokerage business, but was soon attracted to the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago. He obtained a position as a janitor of a large machinery exhibit. After he proved invaluable at keeping the exhibits operating, he was placed in charge of the display. It was there that he saw the vast possibilities of the amusement business and decided to make it his life's work.

But since the World's Fair craze hadn't yet started, Thompson ended up in Nashville, Tennessee holding down a $15 per week draftsman job and going nowhere. He saw a future in architecture, but he was easily distracted and lacked drive. When city officials began preparing plans for a fair in 1896 for Nashville, they announced a contest for would-be architects and offered cash prizes for the design of pavilions and buildings. One of Thompson's imaginative designs won him $2500.

Although Thompson didn't have any show business experience, his uncle, who had done some unpaid for construction for the exposition, turned over to him a failing attraction called the Blue Grotto. "Fred," he said, "run this show and see if we can pull out money out." Fred deduced that its paper mache Capri cave and grotto wasn't very thrilling or even humorous, yet it would require all his instinctive showmanship to make it successful. Instead of hiring barkers, he recorded the outside lecture on an Edison recording cylinder, set it on a rotating turntable and let the marvelous new talking machine attract patrons. The novelty saved the Blue Grotto and Thompson had launched himself with a career in the outdoor show field.

Encouraged by his success, he sought his next exposition challenge. When Omaha's Trans-Centennial Exposition opened in 1898, Thompson was there with a cyclorama called Darkness and Dawn, a heaven and hell illusion. Unfortunately for Elmer S. Dundy, a Nebraskan promoter and politician who had a similar attraction called The Mystic Garden, Thompson's attraction was the hit of the midway.

Elmer Scipio ("Skip") Dundy was born in Omaha, Nebraska in 1862, the son of a Federal judge. When Skip was a boy, Buffalo Bill Cody, Indian fighter and circus promoter had been a frequent visitor to the Dundy home. He filled the youngster's head with a fascination for side shows. After he began working as a bored clerk of the court under his father, all he would do was dream of a career in show business.

By the time he was in his early twenties, he had become a slick and persuasive man, and as a pitchman he had an excited stutter that gave his words a sense of urgency. He also had a talent for making money and he could lose it with just as much flair. He was a tall, handsome man but was sensitive to his premature baldness. He loved tough competition and usually overcame whatever got in his way. In arguments he sometimes won opponents over by removing his center-parted toupee and placing it in his pocket while he continued his stammering train of thought. It was a move that was deliberately calculated to stun his opponents.

Dundy was hopeful that when Thompson declined to do the exposition's second season, his drab walk-through attraction, The Mystic Garden, would make money. But the unfortunate second year extension of the Fair, known popularly as "the hangover," proved disastrous for all involved. Dundy lost $46,000.

In the meantime Frederic Thompson enrolled in study courses at the Art Students' League of New York from January 1899 to October 1900. He studied under W.A. Clark, George Bridgman, Frederic Dielman and Kenyon Cox. It was there while working in his studio on 26th Street that he accidentally conceived the "Trip to the Moon" attraction.

While trying to solve the problem in his Darkness and Dawn attraction of how he could get people across the Chasm of Fire, he thought of an airship among other ideas. But then it occurred to him that he could do an entire show if he could take his audience someplace special, like "To the Moon." He awakened his roommate to tell him that he was going on "A Trip to the Moon," and encouraged his roommate's enthusiasm nearly developed the entire concept before he retired for the night.

When Thompson arrived in Buffalo, New York in 1900 to apply for concession space for the Pan American Exposition, he discovered that Dundy had already applied with a pirated duplicate of his Darkness and Dawn attraction, one that he had failed to patent. This time Dundy resolved to dominate the midway and the Fair officials went into conference to decide their fate. Dundy, better at back-stage politics than quick tempered Thompson, easily won. But since Thompson admired Dundy's business management skills, he approached him about a partnership on a secret show that he had planned for the Exposition if Dundy would let him in on his Heaven and Hell concession. "For years people have been content to sit and watch a cyclorama about a garden of battle," he explained, "but now they are getting bored. They want something new. They want movement and action. Suppose I show you a cyclorama which will make the audience move at the same time." "G-g-g-go ahead," Dundy stammered. Once Thompson demonstrated his "Trip to the Moon" attraction, Dundy readily agreed to join forces.

On April 17, 1900 the Exposition's executive committee announced that it had awarded Thompson and Dundy a concession called the "Trip." The Buffalo Express gave a short description. The "trips" would be made at ten minute intervals and by a "combination of electrical mechanism and scenic and lighting effects .... to produce the sensation of leaving Earth and flying through space admidst stars, comets and planets to the Moon." The "airship" was to have huge wings and large propellers operated by powerful dynamos. It would also contain complicated mechanisms to provide the craft's "Anti-Gravitational Force." The building would be divided into three sections: "The Theater of the Planets," "The City of the Moon," "and the "Palace of the Man in the Moon."

They broke ground for the Trip to the Moon's 40,000 square foot building on July 28, 1900. It was to be one of the largest buildings on the Midway situated between The Old Plantation and the Glass Factory. It was also the most expensive, costing $52,000 (some sources say $84,000) at a time when single-family homes sold for $2000. The building's exterior was completed by mid-September and by then was guarded night and day by watchmen to ensure its interior construction secrets remained so.

Thompson meanwhile advertised in the show business trade papers for midgets and giants to act as Moon Selenites. Gaston Akoun, Manager of the Midway's "Streets of Cairo," hired some in Paris. Eventually he had a cast from a dozen countries; 30 dancing Moon maidens, 60 Lilliputians and 20 giants. This generated fantastic publicity.

Although the Pan American Exposition opened on May 20th instead of its intended May 1st date, his ship now called "Luna" wasn't quite ready to fly. Besides the numerous daily electrical failures that the expo experienced with the recently harnessed power source, the ship itself experienced last minute technical difficulties. Thompson cleverly disguised the embarrassing problems with fanciful stories in the press. One Buffalo newspaper reported on May 12th that "Luna suddenly broke away from her moorings and soared upwards, taking part of the temporary roof of the Trip-to-the-Moon building with her." Three days later they reported that luckily the Lick Observatory in California had located the runaway ship and that it would be back in Buffalo and be ready by Decoration Day.

Finally all was ready and at 7 P.M. on May 23rd, "Luna" made her first public trip. The crew, which staged 30 or more, twenty minute trips per day at 50 cents per trip, increasingly became more proficient. This included the airship's crew of nine, dozens of performers in the Throne Room, another dozen or so in the Grotto of the City of the Moon, and a maintainence staff of ten. The attraction became so popular that the seating capacity was doubled by October. It would have made considerable more money if it had been designed with greater capacity.

Besides their Trip to the Moon and Heaven and Hell attractions, Thompson and Dundy operated the Giant See-saw, the Old Plantation and several other rides at the Buffalo Exposition. They corralled most of the visitor's spending money at the fair.

After the Exposition closed Thompson, facing a three year gap before the 1904 St. Louis Exposition, went to New York. He negotiated with George Tilyou to bring their "Trip to the Moon" attraction to Steeplechase at Coney Island for the 1902 season. Although it was a rousing success in an otherwise dismal season at the resort, Tilyou in a calculated move, asked for a larger percentage of the profits. Instead Thompson and Dundy leased Boyton's Sea Lion Park, and with $700,000 in borrowed money, created Luna Park.

NOTE: Sea article on LUNA PARK.

After Luna Park became an immediate and stunning success, backers like "Bet a Million" Gates had confidence in them to conquer Broadway. They had complete faith in Thompson's proposal to build a showcase theater for spectacle modeled after the European indoor circuses, Hippodromes as they were called.

Thompson designed a building a block long and gave it the appearance of an Arabian Nights fortress. Its innovate stage, 110 feet deep and 200 feet wide, was large enough to hold 600 people. The stage was divided into twelve sections, which could be raised or lowered hydraulically. Since he planned to have streams, lakes and waterfalls in the show, he designed the stage apron to drop 14 feet, forming the base of a tank. Spillways under the wings filled the tank, and huge pumps capable of circulating 150,000 gallons per minute provided the water effects for ocean storms or raging cataracts. A network of overhead cranes could shift scenery weighing up to ten tons. The stage, including all of its machinery and structural supports weighed 230 tons. Beneath it in the basement was a zoo where the animal acts were housed.

Construction started in July 1904. Cranes hoisted over 15,000 tons of steel to form its balcony and roof. The roof's four enormous steel trusses were the largest ever used for a building at the time. The interior walls of the theater's promenades and auditorium were lined with marble elephant heads whose golden tusks held electric globes at its ends. Five thousand additional lights formed a sunburst on the ceiling. The stage, which used 9000 more lights, required a light board so large that it had to be worked by a team of men from a platform 30 feet high.

The New York Hippodrome Theater's grand opening was on the evening of April 12, 1905. A long line of chauffeur driven autos and steam carriages awaited their turn in front of the theater's brightly lit marquee to drop off its passengers. Among the 6000 richly dressed patrons, who gathered for the premier, were Manhattan's rich and famous; Senator Chauncey M. Depuy, architect Stanford White, Harry Payne Whitney, Gladys Vanderbilt, and of course steel magnate "Bet a Million" Gates.

Playwright George V. Hobart had put together an opening epic called "A Yankee Circus on Mars," a light fantasy about a New England tent circus' trip to the "red" planet. It starred Elfie Fay. The more dramatic part of the bill was "Andersonville: A Story of Wilson's Raiders," scripted by dramatist, Carroll Fleming. There were also performances by vaudevillians and circus stars.

During the autumn of 1905, Thompson and Dundy replaced their "Andersonville" show with "The Romance of a Hindoo Princess," an exotic thriller of old India. It featured a gigantic battle climax where the evil Killer Khan's elephants battered apart the palace gates. But when they were counterattacked, and had to retreat, the big finale featured the elephants and soldiers in a massive slide down a mountainside to their deaths and into a lake. The Khan's army was vanquished.

In December, they outdid themselves with the production of "A Society Circus." Although the show had an awkward story, it was an opulent fantasy spectacle with a gypsy caravan encamped on Lady Volumnia's estate. It featured a cast of baroque villains and the nobility as leads. It was more stunning and impressive than "A Yankee Circus on Mars." It was proclaimed a hit by the worshipable reviewers. Thompson and Dundy could do no wrong.

Frederic Thompson and Skip Dundy's personalities complemented each other nicely and served as a check on each other. Their partnership operated on the basis of complete trust. Thompson, who was ten years younger than his partner, concentrated on showmanship while Dundy worked on finances. Thompson drank excessively and wasted money. Dundy would gamble on anything and was proud of his female conquests.

When Skip became immersed in one of those card games when $50,000 dollars would ride on a single hand, only Thompson could lure Dundy away on the pretext of a talk about a future attraction. When Dundy found Thompson drunk as a skunk at a Coney Island bar, he would stride in and snatch the glass from his hand and hurl it to pieces against the floor. And when Dundy slipped into a messy love affair, Fred Thompson would offer common-sense advice.

The years 1906-1907 proved disastrous for their partnership. First Thompson married Mabel Taliaferro, an actress on February 29, 1906. Out of blind love, Thompson decided to make his wife a star. He plunged headlong into a new field of dramatic production to please his wife while neglecting his carnival work and his amusement park. What was more important was that he deprived Skip Dundy of his companionship and advice. Without Thompson, Dundy let his frantic pace run himself ragged. Skip Dundy's sudden and unexpected death, from dilation of the heart and a severe pneumonia attack on February 5, 1907, left Thompson rudderless.

Thompson was a spendthrift both at his park and in his private life. In an interview with Everybody's Magazine in September 1908, he estimated that he spent $2,400,000 on Luna since he began building it. His lavish operating expenses, including the cost of rebuilding and installing new shows, were $1,000,000 per year for only a four month season.

His personal living expenses were tremendous and he wasted money like it was from a bottomless barrel. For example, when his schooner Shamrock won the $1000 Lipton Cup in 1908 during an ocean race to Cape May with Thompson aboard, he rewarded the captain with $38,000, a thousand dollars for each second that he broke the record. He lived extravagantly above one of Broadway's best restaurants and installed a dumbwaiter so the chefs below could send up their cuisine to be served by his two Japanese butlers. Afterwards he would tour the the "Great White Way's" night spots from Langacre Square to Madison Square accompanied by his fun-loving friends. He would pick up checks and leave lavish tips, and as he strolled he would toss gold coins to anyone he cared to please.

Thompson's drinking problems began to worsen. Still at times, when he was clear-headed, he was capable of handling his great work load with little slip in schedules. In a way his drinking gave him the illusory freedom and eased his tension from overwork.

His marriage to his wife was always in trouble. She was always on tour in the title role of "Polly of the Circus", the result of a smash 1908 hit he produced that restored her career. Finally they divorced in 1911. Then when his financial problems became acute, he had to file personal bankruptcy in 1912. Although it was estimated that he was worth $1,500,000 at the zenith of his career, in the end he had $665,000 in debts and little in assets. He lost his beloved Luna Park to his creditors.

After Luna's loss Thompson found a managing job in Manhattan with theater promoters Klaw and Erlanger. He remarried in 1913 to a girl from Nashville, Tennessee. However, his real love was the World's Fair midway and he opened a show called "The Grand Toyland" at San Francisco's 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition. Unfortunately it was during World War I and patrons were more interested in seeing and riding airplanes, the fair's big sensation. His show's playful adult illusions was considered old-fashioned. He returned to New York a failure and broke.

His friends arranged a benefit for him at Luna Park in 1916. Since he was considered a show business monarch at Coney Island, 50,000 people mobbed Luna Park and $30,000 was raised for his benefit. His friends wanted to use the money to build a house for him, but just two weeks later he had to undergo a critical operation for Bright's disease. He nearly lost his life. His health worsened, weakened by years of alcoholic excess and self-doubt. He needed major surgery again in 1918, and once more in 1919. His recovery was in doubt for he lacked the strength for the ordeal.

New Yorker's were suffering through a heat wave and a bout of stifling foul air. Thompson's condition worsened and he died at 5:30 A.M. on June 6, 1919. Some of his Coney Island friends took up a collection to buy a headstone for his grave.