Coney Island - Second Steeplechase Park

(1908-1964)

Revised May 20, 1998

The task of rebuilding Steeplechase in time for the 1908 summer season was George Tilyou's priority. None-the-less it would be an expensive undertaking because the municipality, fearing another fire, banned all combustible amusement structures. Tilyou's new buildings would be rebuilt with steel, glass and concrete instead of wood.

The new park was financed with a $2,000,000 stock issue; 400,000 shares at $5.00 a share. Tilyou then hired the P.J. Carlin Construction Company to build his show piece Pavilion of Fun designed by architect Reynolds S. Hinsdale. The 450 foot long by 270 foot wide building (2.8 acres), constructed of steel and glass with a wooden floor at a cost of $450,000, would enable Steeplechase to draw crowds in the event of inclement weather. It would contain a dozen of his most popular attractions.

Tilyou also planned a $600,000 Palace of Pleasure, in French Renaissance style and capped by a central dome with a rotunda 65 feet in diameter. Next to it and also facing Surf Avenue would be a large ballroom decorated in Louis XIV style. Beneath its translucent glass roof would be a 40,000 square foot floor for a thousand dancing couples, and surrounding it a fifteen foot wide balcony with seating for several thousand more. His park would include a figure eight roller coaster, a scenic railroad, a bathing pavilion and pool, a rose garden and 1600 foot long pier. He planned a trolley car along the edge of the pier to transport passengers arriving by steamship to the center of his amusement park.

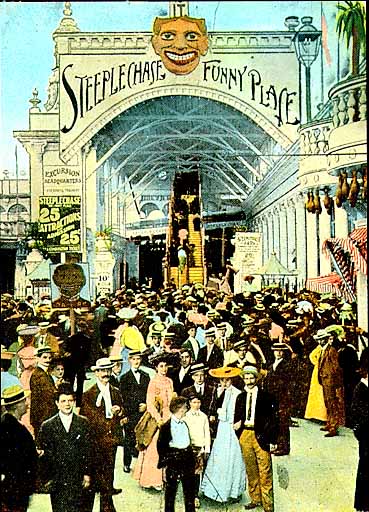

| The Steeplechase entrance on the Bowery. - 1908 |

The new Steeplechase opened on Sunday May 17, 1908 to large crowds who came to see his new attractions. Park employees were dressed in fancy uniforms consisting of red coats with green lapels and cuffs and would be dubbed "redcoats." Bands entertained patrons with rousing marches and other popular music on a platform in the Sunken Garden.

Some of Steeplechase's buildings like his Palace of Pleasure and Ballroom wouldn't be ready until the 1909 season. Others like his refurbished Ferris Wheel and See-Saw rides were salvaged from the old park. Luckily only the bottom few cars of the giant wheel had burned and the steel structure was undamaged.

The Pavilion of Fun was encircled by a longer and much improved Steeplechase Ride, built at a cost of $100,000. Actually there were two race tracks, a high track and a low track, each with four horses seating two riders racing along guided rails parallel with each other. The slightly longer course, about 1700 feet with a higher starting point, was one lap around the building's exterior. The 1600 foot long inner track with a lower starting point, ran under the colonnade roof on the W. 16th side of the building and thus was protected from the elements. The rider's horses, drawn up a cable to an elevation of 22 feet at the start of the race, suddenly dropped downward along a 15% grade wooden track to gain speed. The riders then plunged across a miniature lake, while their momentum carried them upwards again to a height of 16 feet beyond the beach. The riders then descended through a tunnel and raced upwards over a series of dips representing hurdles until they reached the finish line far ahead. While heavier riders had the advantage, usually the horse on the inside rail won, especially on the shorter course.

| The Steeplechase ride with the Pavilion of Fun in the background. |

The departing riders were then guided towards the Pavilion of Fun's Insanitarium and Blowhole Theater. There was no alternative. If they about-faced in the corridor, they wandered through a maze before returning by another route to the stage. A typical couple would enter the stage on their hands and knees through a low dog house where they would confront a cowboy, a tall farmer and a dwarf clown. There was no escape as they timidly filed past a railinged alley called the Comedy Lane. While they were distracted a system of compressed-air jets would blow men's hats off the unwary and send woman's heavy dresses swirling upward. It was a big deal in 1908 just to see a woman's ankles. One of the farmer's favorite tricks was to take a pair of prop bloomers hanging on the limb of hot-dog stage tree and offer them to the girl, on the theory that they had just blown off in the hurricane. In the distance, the crowd would howl.

| The Pavilion of Fun's Insanitarium. |

Sometimes the clown prodded the man's buttocks with an electric stinger. He would leap in surprise just as the floor beneath him gave way. His gal would reach out to help, but she would be caught by surprise again with a blast of air and watch helplessly as her shirt soared above her waist. The embarrassed couple would hurry by six foot high playing cards, a tree with six foot long hot-dog branches and a dwarf clown who would swat them with a slapstick. Finally they would reach a moveable section of floor known as the Battleship Roll. Piles of barrels on either side of the gangway would begin to totter and appear to be tumbling down upon them as they scrambled for safety and escaped out into the anonymity of the crowd.

Meanwhile those who have already been made fools of, watching from beyond the glare of the floodlights got to watch the next victims of this endless parade. Tilyou even offered seats below for those who wished to linger to watch the show and roar with laughter. Amazingly there were rarely any complaints. It was if patrons realized that the monkeyshines that they just endured was precisely what they came to Coney Island to see and experience.

During the next three years Tilyou installed a number of novel attractions, mostly inside his Pavilion of Fun. The most interesting was the Human Pool Table, a large flat surface made up of 24 large rotating discs. It was set up so that adjacent discs revolved in opposite directions. The people became "players" as they attempted to cross its flat surface, but lost their footing as they were spun every which way and became entangled with others doing the same.

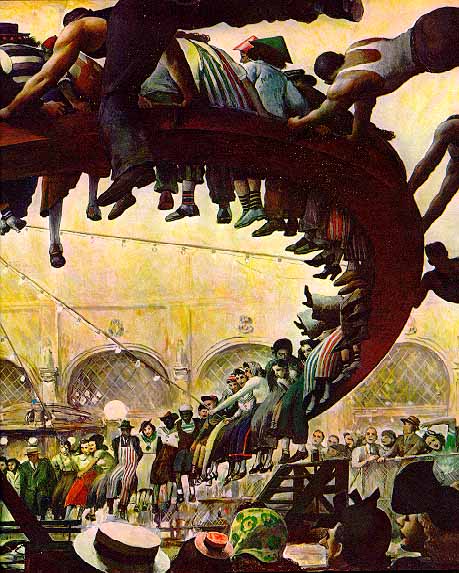

| The Hoopla in the Pavilion of Fun |

Other attractions in the Pavilion were the Human Niagara, an inclined bumpty bump slide with 60 ball bearing rollers, a Mechanical Jackass that offered a prize for a successful ride, a monster elephant and the South Pole. The Mixer was another popular attraction. It was a big revolving platform 30 feet in diameter with enough room for about two dozen people. As it spun faster and faster it catapulted people into its surrounding scoop like hollow. One unusual attraction was called the Grinder. It was a huge sausage machine where people entered one end, squeezed through soft rollers, and were dumped out at the other end.

| Inside the Pavilion of Fun. - 1912 |

Carousels were popular with the public and Tilyou obtained some of the finest. His first in 1908 was the Chanticleer built by Fredrick Savage. Since it featured 38 chickens and 14 ostriches instead of horses, it was dubbed the "Chicken Carousel." It was located on the lawn between the Pavilion of Fun and Surf Avenue. The other was installed in the Pavilion of Fun in 1912. It was the famed El Dorado German carousel, carved by Hugo Hasse of Leipzig, that had been installed at a cost of $150,000 in a hippodrome on Surf Avenue at W. 5th. It had barely survived the 1911 Dreamland fire with paint blistered from the heat. Tilyou salvaged it and restored it. It was a menagerie machine with three platforms arranged in ascending tiers, each revolving at different speeds. Its crown-like canopy rose to a height of 42 feet, was illuminated with 6000 lamps and it featured horses, pigs and other barnyard animals.

Accidents were always few and far between, but there were two serious ones within a week during the 1912 season. A man was killed on May 19th when he fell off the Wooden Donkey. The object was to ride on its revolving back for five minutes in order to win a $5 prize. Then on May 26th five people were injured when the cable on the Airship snapped and dropped one end of a car. The passengers tumbled out and hit the ground. Fortunately the ride as slowing down and wasn't very high off the ground.

Steeplechase had always offered its paying customers free use of its fenced "private beach" in front of the park. In fact, having a title to the property was advantageous since over the decades sand had built up and extended their property. However, when their right to deny beach access to the public was challenged, they lost the court case on Oct 4, 1913. Although they showed title to "a conveyance in fee to land extending out into the Atlantic Ocean," the judged ruled that the public had a right to use the beach in the area between mean low and high tides.

George Tilyou added a number of outdoor attractions through the early teens including an Ocean Roller Coaster on the beach side of the park, revolving Airships, Venetian Gondolas, and a tracked Automobile ride on a quarter mile track that used full sized autos. But then George Tilyou died in 1914 when his eldest son Edward F. Tilyou was only eighteen.

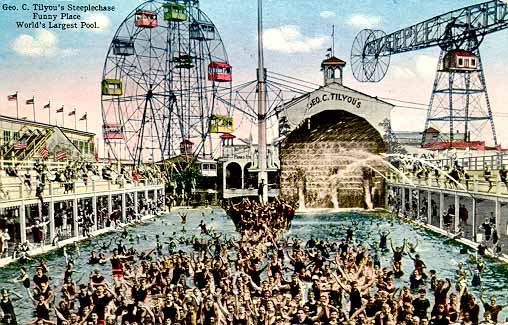

| The World's Largest Swimming Pool |

The park continued to be innovative, but on a different note. The older popular attractions, particularly in the Pavilion of Fun were retained, but most of the outdoor attractions were replaced with more thrilling rides. The biggest changes in Steeplechase's outdoor amusement rides occurred in the early 1920's. Several of the popular rides added in the early 20's were the Frolic, a circular spinning ride where the suspended cars tilted outward, a Dodgem' bumper car ride, the Witchway, a swing that whirled passengers around, and a Caterpillar flat ride.

Edward Tilyou also made several changes inside the Pavilion of Fun. In 1920 he set aside a play area in the southeast corner, just for young children, called Babyland. It featured two miniature slides, two hobby horses and a kiddie carousel with 24 miniature horses and two chariots. Earlier in 1915 he had converted the unused space above the restaurant near the balcony and built a skating rink.

| A 25 cent Combo Ticket, good for one turn on each attraction. |

Since horse racing rides were so popular, they bought a Racing Derby Carousel in 1920 from Prior and Church, a Venice, California firm. It was innovative in that 16 groups of horses racing four abreast on a 315 foot circumference platform at speeds of nearly 25 MPH. The horses, which were set in six foot long tracks, would move back and forth as the ride rotated, sometimes nosing ahead to gain the lead, other times suddenly falling back. It was impossible to determine ahead of time which of the four horses would win since the cables that moved the horses back and forth criss-crossed beneath the platform. It was an exciting one mile race and winners of each race would be given a free ride. The ride was located in from of the Chanticleer, within easy viewing of the curious public watching on Surf Avenue.

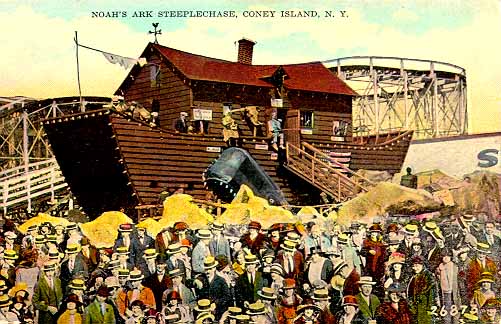

The opening of the Reigelmann Boardwalk in 1923 and the widening of Surf Avenue during the following winter gave management an incentive to renovate the areas adjacent to them on both the north and south side of the park. A new roller coaster called The Limit was built on the beach area facing the corner of W. 19th and the Boardwalk. An Old Mill tunnel of love water ride beneath the Tilyou apartment along W. 19th, and a Noah's Ark catered to the tastes of parents with young children. The later, located adjacent to the newly built Boardwalk, and beach side of the new roller coaster, was an old fashion fun house that rocked like a boat. Inside was a mirror maze, moving floors that nearly knocked one off their feet, and hidden compressed air jets that blew woman's skirts high in the air. There was also a menagerie of animals that Noah and his wife saved from the Flood.

| The Noah's Ark with The Limit roller coaster in the background. - 1925 |

On December 31, 1927 Thomas F. McGowan, Steeplechase's first general manager, died. The choice for his replacement was Edward F. Tilyou's and surprisingly he offered young Jimmy J. Onorato the job the following day. The announcement naming Jimmy as General Manager of Steeplechase Park, since he wasn't quite 20 years old, was resented by some of the older year-round staff. Many believed that he was too young to manage the park. While employees assumed that Edward F. Tilyou would manage the park's daily operations during the summer, he didn't want the job. He was content to set general policy and give the young manager the authority to implement it.

James Onorato had been trained carefully by his mentor Thomas F. McGowan. He had begun working as a ten year old during the 1918 summer season at the park making change in the Penny Arcade. He was paid $5 (71 cents / day) for a seven day work week. The following summer he began running errands for park employees and was placed on retainer at $5.50 / week. Then on July 23, 1923 at the age of fifteen, he was given the important and trustworthy job of keeping the records of the park's daily receipts and the weather on an hourly basis. It was a job that made him privy to the park's income and hence the Tilyou's wealth. Shortly afterwards, when his Jimmy's father suddenly passed away, he dropped out of high school just weeks before his graduation to work full time to support his mother, younger brothers and sisters.

After the 1928 season ended the heated indoor pool at the seaward end of the Pavilion was demolished. Then the park spent $4000 in 1929 to purchase a Hey Day ride that was installed above the pool's pit. Steerable cars on the elliptical shaped track were attached via a slot in the platform to a cable running beneath. The driver could spin the wheeled cars around to face backwards as they were pulled around the track counter-clockwise. In addition Custer Cars, miniature gasoline powered cars on a serpentine track were installed adjacent to the Boardwalk.

The Pavilion of Fun featured some novel "fun devices." The Funny (revolving) Mirrors had a six inch wide row of nails encircling the mirrors. When a patron came along, the individual received a mild shock when he leaned on the rails to see the funny images in the mirrors. If he tried to take a seat to look at the mirrors, he was surprised when the seat suddenly collapsed by four or five inches beneath him. A stereoscopic viewer nearby had a blowhole at its pedestal so when a woman looked at a picture, her dress blew upwards. And the California Red Bats exhibit, placed in a small cage at the top of a steep ship's ladder, was merely two miniature baseball bats painted red and accompanied by a sign inside urging "Don't tell anyone!"

After the stock market crashed in 1929, business began to taper off. But before spending money became really scarce in the depths of the Depression, numerous changes were made along the Boardwalk. Mangels installed a magnificent Boardwalk Carousel at the corner of W. 16th for the 1930 season. It was known as the 72H carousel; a Mangels frame with 72 Illions horses and two chariots. Music was provided by an Artizon band organ. The Whale replaced the Noah's Ark along the Boardwalk the following season and Mangels installed an eight car Whip beside it.

For the 1933 season the park built an arena for a one-ring circus between the pool and The Limit roller coaster. Acts were booked through Wirth and Hamid impresarios. The first free show lasting 45 minutes was on June 2nd with its elephant, Rosie, a hit with the children. Other acts included Leon's Performing Dogs, a tumbling act, three men with a bucking mule, and a clown act. Since most of the opening acts were weak, they made numerous changes, almost weekly, by August. The public and park management liked the Riding Waltons, Pelot & Wilson - juggling clowns, and Silver & Company - a man and a woman trapeze act, the clown act and Big Rosie the elephant.

Facilities for children were always a management priority. A small one foot deep circular Children's Wading Pool had been built the previous season along with an elongated semi-circular diving pool between the big pool and Surf Avenue.

The big outdoor swimming pool was where the park's beauty contests were judged during the summer. While the Grandma's Bathing Contest in mid-July was new that season, the Venus Bathing Beauty Contest had been running the first Sunday in August since 1922.

It was at the outdoor pool on Tuesday August 1, 1933 that Steeplechase's worst accident took place. The pool area was crowded with 1000 bathers and some choose the shaded west balcony to escape the hot afternoon sun. At 3:30 P.M. a fight broke out between two men along the pool's deck. A lifeguard attempted to break it up, but four others began taking sides. Those in the balcony, eager to see, crowded along the railing several deep. Suddenly without warning, with only the sound of splintering wood of the supporting posts, the railing gave way at the same time as a portion of the floor collapsed. About 80 men, woman and children fell 17 feet to the pool deck below with some luckily landing on bathhouse roofs only 7 feet below. 54 people were injured with only a few seriously. The balcony's support posts just couldn't hold the weight of some many people at one time.

Onorato, ever aware of ride safety, was meticulous in inspecting and repairing or even replacing the slightest worn part. He and his staff of 30 year-round employees would disassemble a ride completely during the winter months and completely rebuild it. And during the summer season they would inspect each ride before the park opened and even walk the entire track of the Zip roller coaster and the Steeplechase Horses, ever looking for the slightest flaw in the track.

Despite precautions, accidents were bound to happen. The majority were friction burns on the Whirlpool, Down and Out Tube, Bowery Slide and Human Pool Table. Steeplechase's policy was to apply first aid at the nurse' office and pay for any damaged clothing; about $50 in today's dollars. Although the park was covered by insurance, management attempted to settle damages before patrons left the park and once home contemplated how much they could sue for.

There were very few times when the park was fully to blame for accidents, although the courts sometimes didn't agree. Several people were seriously hurt when they stupidly stood up on the Whip and were thrown from the cars. Others were injured during falls in the park's three rotating barrels, and a few patrons even fell off the Steeplechase Horses. The most tragic accident occurred on August 6, 1935 when 10 year old John Barke fell off his horse at the second turn and plunged ten feet to the wooden platform below. He suffered brain injuries and died. Nine years later a girl fell out of a car on the fast moving Silver Streak and was hospitalized.

During the Depression new attractions were postponed at Steeplechase as well as other amusement parks. The lack of new ride orders forced most manufacturers into bankruptcy. However, after the worst was over in 1933 and business began to improve Steeplechase placed an order for an innovative new ride called the Flying Turns. It was a bobsled ride where a train of two passenger cars on swiveling rubber wheels ran through a cylindrical wooden chute made of cypress wood. Cars dropping from the traditional high lift hill shot around the tight figure eight course nearly perpendicular on turns. The exciting ride was the result of a partnership between roller coaster designer John Miller and Norman Bartlett and cost $50,000 to install for the 1934 season.

On December 19, 1936 the Steeplechase Pier was damaged by a barge that was extending nearby rock jetties. It broke loose from its mooring and smashed into the pier and destroyed the house at the pier's seaward end. To save money the pier was never rebuilt to its original length.

| Aerial view of the 1939 fire. The Flying Turns toboggan coaster is burning on the right. |

Three years later on September 16, 1939 disaster struck when trash beneath the Boardwalk caught fire and spread into the park. The fire, fanned by an afternoon on-shore wind, for a time threatened the entire park, but 52 pieces of fire equipment with the help of two fire boats contained the blaze and brought it under control two hours later. The Pavilion was saved by a screen of water and by the park's own fire crews lead by Vito Onorato that worked atop the Pavilion's three roofs. The popular Flying Turns ride burned and fire gutted the Bicycle ride, House of Glass, Cake Walk, Barrel of Fun, band stand, the Circus back stage area and a 220 foot portion of the Steeplechase track. Edward Tilyou estimated the damage at $500,000 and ordered workers to spread sawdust over the water soaked areas so that the park could reopen at 7 P.M.

It was fortunate that Dr. Courtney was displaying his premature babies at the 1939 World's Fair. He had previously exhibited his "preemies" in a Baby Incubator facility on the Boardwalk Ramp in front of Steeplechase from 1936 - 1938.

It hadn't been a very good summer either. Attendance at the park, and in fact all of Coney Island had been lighter than usual because of competition from the nearby World's Fair at Queens' Flushing Meadows. Since the summer of 1940 was expected to be the same due to the fair's two year run, the Tilyou's decided just to clear the damaged area. The rising cost of lumber and steel made it impractical to rebuild the Flying Turns, and replacing the 220 feet of the damaged Steeplechase ride's steel track convinced them to operate only the four horse inside track afterwards. Insurance only paid $92,501.10 for the damaged rides.

When the Huber lease for the park's western five acres came up for its ten year renewal, the family offered it for half ($15,000 / year) of its previous fee. They were worried that the Tilyou family might cut their losses after the disastrous fire and sell off the park.

Edward Tilyou who visited the World's Fair that first season was very impressed by the Fun Zone's Parachute Drop at the Fun Zone's Lifesaver Exhibit. He knew that he had to have that unique attraction for his Steeplechase Park when the World's Fair closed in October 1940 and was prepared to agree to Retired Naval Air Commander James H. Strong stiff terms. His design, which was patented in August 1936, included a strong high steel tower with electric motors to tow the chutes upward and a series of eight guide cables in a circular arrangement about the chute to prevent swaying and dangerous contact with the tower. While he originally invented the tower as a training device for the American armed forces, he was pleasantly surprised in 1936 - 1937 when hundreds of passing motorists stopped by his estate in Highstown, New Jersey to request rides while he was testing it.

Tilyou agreed to purchase the attraction for the exorbitant price of $150,000. But the ride purchase also came with a lease agreement that paid a commission of 10% on the first $25,000 of ticket sales and 7-1/2% on the second $25,000 of ticket sales. It was agreed that all replacement parts would be purchased by the ride manufacturer. Still it was difficult to recoup the investment with a ticket price of 27 cents + 3 cents tax since the ride was labor intensive, requiring three operators for each chute. It was also too sensitive to wind conditions to turn a profit without steady crowds. Yet by placing it along the Boardwalk with a separate entrance and not including it on the park's combo ticket, they expected to eventually make a profit.

Steeplechase made only a few changes for the 1940 summer season. The Boardwalk entrance, with the future Parachute ride in mind, was designed so it wouldn't interfere with the view of the tower. Instead of an enclosed entrance that offered rain protection as before, the new entrance was open to the sky. The concrete and steel ramp was wide and in one area at the top of the ramp, visitors crossed grates where huge fans hidden below were adept at sending the unwary woman's dress skyward. Along the Boardwalk area the concession stands were replaced with a long brick structure that housed four concessions. The area in front of the Pavilion where the Flying Turns once stood was turned into a lawn where the new gas-powered Express Train operated. Inside the Pavilion the Flyers (aka Dangler) was moved to the center of the building and a new Bicycle Carousel was set up in its place. The Gondolas would see their final season.

Finally in 1941 they began spending money for new attractions to fill in the area adjacent to the Boardwalk. The newly purchased Parachute Jump from the New York World's Fair Lifesaver Exhibit was erected during April and May on a large reinforced concrete base. The 80 foot tall Giant Swing was revamped with six - 6 passenger aluminum Buck Roger style rocket cars at a cost of $4100. They installed a brand new 12 car Whip from Mangels on the Surf Avenue side of the park, and along the Boardwalk, the Silver Streak at a cost of $9750. The later was a circular flat ride on a 30 degree tilt with two-passenger cars traveling around its perimeter at 30 MPH.

The 262 foot tall parachute tower, erected just west of where the Flying Turns once stood, had a capacity of twelve - 32 foot diameter chutes. Passengers strapped into a canvas seat were hoisted to the top of the tower. A mechanism tripped the descent and the already opened but limp chutes blossomed wide to slow the fall. Rubber dampers smoothed the landing. It gave the brave passenger a simulated feel of what it was like to jump out of an airplane, something that many men and boys thought that might be useful during a war that seemed just over the horizon. World War II came unexpectedly when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

| View of Steeplechase's Pavilion of Fun and Parachute ride from the beach. |

War time regulations beginning in 1942 curtailed much of the gaiety at Coney Island's parks. They were allowed to remain open for public morale, but dim-out regulations required that the lighting couldn't be seen by overhead enemy planes or by off-shore submarines. Night illumination was with soft blue and dark purple lamps. Even most of the lamps on the El Dorado carousel inside the Pavilion of Fun were dimmed and Steeplechase was dark and dreary at night. New attractions, and even building material for repairs were difficult to obtain. James Strong, designer of the Parachute Jump had to travel to Washington D.C. to obtain a rubber ration for the ride's shock absorbers. Labor shortages to run the park was also a problem as many employees either volunteered for service or were drafted. Onorato had to hire elderly staff and women for the 1943 season and cut back on hours by closing Mondays.

Onorato was concerned that Steeplechase might not reopen for the 1944 season. He was being drafted, Edward Tilyou was dying, Frank Tilyou was in the Navy, and George C. Tilyou, Jr. wasn't prepared for the task of managing park. Onorato was nearly 36 years old when he was drafted, and was accepted by the Army on his birthday (February 19th). However, on the night before reporting to basic training, President Roosevelt gave a reprieve to men older than 35. Still it was difficult to staff the park. During 1945 only the outside rides operated until just after World War II ended. A few of the Pavilion's attractions reopened during the final few weeks of the summer season.

Edward F. Tilyou after a long illness died on June 19, 1944. The park remained closed for the following three days. His two younger brothers George, Jr. and Frank along with their sister Marie faithfully adhered to their father's successful formula and continued to operate the park. After Luna Park burned and closed that summer, they had little competition.

Sibling rivalry was always a problem in the Tilyou family and increased after Edward died. Even in the early 1940's before his death when he lived at Lake Placid for months at a time and traveled extensively, he didn't allow his younger brothers, George and Frank, any opportunity to display their talents with regard to Steeplechase. While Edward allowed George to play owner for the media and Frank to dabble with the park's publicity, both felt stifled and resented their brother.

After World War II George and Frank grew apart. George as the elder brother inherited the title and salary as President of the Tilyou Realty Company. Unfortunately everything he did was resented by his younger brother. If George was for something, Frank was automatically against it, and vice versa. The fractious Tilyou family divided into two opposing camps; George and Marie for the status quo and Frank and Mrs. Eileen (McAllister) for change. They each owned equal quarter shares in the company and when they voted, they usually split down the middle.

In 1945 the Boardwalk Carousel, which had been vacant since the beginning of the war, was leased to James J. McCullough, a Tilyou cousin. The following year as the summer resort began to return to normal, Steeplechase instituted Season Bathing only at the Pool. Besides bringing in an early cash flow from selling memberships, it guaranteed a segregated pool as "coloured" people were visiting Coney Island in greater numbers.

In 1947 they cut the ballroom in half to build a TV studio. It was also the final season for the Hoopla inside the Pavilion and for the Eli Ferris Wheel that had been installed in 1939.

After the war Steeplechase abandoned the old combination ticket where the specific ride number was punched when a patron went on a ride. Instead they offered at first, 15 rides for one dollar. Of course very few people paid full price before or after the war. Numerous social, political and religious groups had a designated day for an outing to the park, and received discounted tickets for sale to its members. Free tickets, given to orphanages and church groups, were tax deductible.

The first new adult rides in seven seasons were purchased for the 1948 season. They had to reroute the Express Train to make room for the Scrambler and placed the C-Cruise in the Pavilion. A Kiddie Boat ride and Kiddie Roto Whip were installed and they bought twenty new Dodgem' cars for the Pavilion ride.

The 1949 summer season was a difficult one. A polio epidemic swept New York and many people were afraid to venture where there were large crowds. In July, as a precaution, Steeplechase began adding more chlorine to the pool. But by August, when the scare was at its peak and 60 new polio cases were reported daily in the five boroughs with Brooklyn leading, nobody was swimming in the pool and business at the park was off 25%. The week long Mardi Gras festival during the first week of September was canceled, and unfortunately was only revived a few scattered years during the 1950's.

By 1951 they were offering a combo ticket of eight rides for 70 cents. Thursday was bargain day when the public could get 12 rides for the same price. Kate Smith, America's favorite singer, began her TV show at Steeplechase and they hired a woman lifeguard for the first time. The Skating Rink, that had only been used for private Tilyou parties, was reduced to firewood in December.

In 1952 a decision was made to tear down several antiquated buildings that faced W 19th Street. They demolished the Laundry, old Bathing Pavilion and the Tilyou Residence. Unfortunately the popular but low capacity Old Mill boat ride ran beneath the Tilyou residence and was impractical to rebuild it without spending a lot of money.

Although Steeplechase was closed for the winter, the worst natural disaster to hit Steeplechase since it was founded in 1897 occurred on Saturday November 7, 1953. At 4:30 A.M. George Butler, the night watchman, called James Onorato to inform him that the ocean was on the way in and he couldn't continue his rounds. Although the ocean had never come up to the park grounds before, the Ocean and Coney Island Creek to the east met as the entire Island was suddenly covered by one foot of sea water.

At 6 A.M. a postal worker in his truck discovered a fire at the Boardwalk Carousel. An electrical short had caused a fire, and before fireman could arrive, the entire ride was aflame. The park's sprinkler system on the Boardwalk kept the fire damage isolated to the Carousel. Although 52 horses survived, damages were $50,386.

Unfortunately the park had taken no preventive steps for such an unlikely event and hadn't lifted the motors out of the rides completely or raised them. Pumps were brought in to pump the Pavilion's cellar, sprinkler pits, and swimming pool dry. It took an entire month for a crew of four men just to clean and refurbish the Racing Derby. Onorato was anxious to avoid replacing or rewiring the 19 damaged ride motors. Instead he assigned four men to clean them and afterwards put them in a "hot" house to dry out. While his method wasn't unique, it was endorsed by a nearby family owned electric motor rewiring service.

In 1954 a parking lot was finally built on the old site of the Laundry, old Bathing Pavilion and Old Mill Ride. Management felt that any new structures would be on leased land. They also didn't want to expand the pool facilities because it would give more power to pool members who were becoming more vocal. New attractions for the summer were few; a Poker Roll game on the Boardwalk where the Shooting Gallery had been, and an Optical Viewer, a coin operated telescope, on the Parachute platform.

After Mary E. Tilyou (Mrs. George C. Tilyou), the family matriarch died on August 15, 1954 at the age of 84, her four remaining children inherited their late father's estate. She had been both a trustee of the estate since 1914, and a moderating influence of her children's competing ambitions. Afterwards, instead of working together for the park's benefit, they borrowed money from the Tilyou Realty Company to maintain their individual lifestyles. Money and even potential leadership was diverted from enhancing the park. Eventually any business owned by families unable to cope with sibling rivalries would have gone under, but the Tilyou family was lucky. Steeplechase would be saved by its capable, devoted and loyal general manager, James J. Onorato.

The one persistent problem that management couldn't solve without raising wages was attracting young vibrant employees that would improve the aging park's image. By paying near minimum wage, only pensioners and old men without the burden of supporting families worked as ride operators and ticket punchers. Granted Steeplechase was loyal to employees who worked there for decades, but without new blood, the park began to look like a museum, especially with its antiquated attractions.

No new attractions were purchased for the park during the years 1955 to 1957, but Frank Tilyou through a separate business venture in 1955 placed Sky Fighter and Jolly Caterpillar kiddie rides on the edge of the Parachute platform located behind the brick concession building along side the Boardwalk. They were a flop since they were in the worst possible location. partially hidden from view from the Boardwalk by the building.

While little was new at the park, operations at the park weren't exactly uneventful. The Steeplechase Pier burned down at 3:15 A.M. on April 22, 1955 and two patrons were stuck 30 feet above the ground on the Parachute Drop for 27 minutes on August 6th. They sent two men up to the top via another parachute to fix the jammed mechanism from above.

The Arthur Godfrey Show began broadcasting from Steeplechase in 1955. The one hour television show, produced on location with rides operating and many Coney Island families as unpaid extras, was a publicity coup for the park. On the other hand, the park had to handle the adverse publicity in 1956 when a sixteen year old boy, Daniel Bruns, was shot by a friend at the Pavilion's Shooting Gallery. His careless friend wasn't paying attention that he was holding a loaded rifle. The park managed damage control by giving out the location as their address on Surf Avenue instead of in the pavilion of Fun. This lead most newspaper readers to surmise that the accident took place in a shooting gallery outside the park.

There were only minor changes for the 1958 season. They installed a Kiddie Train, the Comet in the Sunken Garden, which had operated at their Atlantic City Pier. And a tracked dark ride called the Pretzel (aka Shangrila Ha Ha) occupied a 30 foot deep space in the Old Post Office building along Surf Avenue. It would be the final season for three antiquated rides in the Pavilion; the Zoo, Kiddie Airships and Bowery Slide. At the end of the season the rebuilt Steeplechase Pier reopened.

George C. Tilyou, Jr. died after a major stroke on December 26, 1958. A month later Marie H. Tilyou assumed the Presidency of Steeplechase Amusement Company, which was had been held by James Onorato since 1932. Onorato was demoted to Treasurer and was retained as General Manager. His demotion was kept secret, even from his brother. To smooth over any ruffled feelings, his salary was raised $500. James Onorato, despite having had job offers from other amusement park operators like Walt Disney, followed his mother's advice and choose a safe course. There was more at stake than his job alone since several brothers, other relatives and friends were employed by Steeplechase. Besides he liked living in Brooklyn, and for him, managing Steeplechase was fun.

Replacing many of Steeplechase's antiquated rides became a high priority now that Marie had become the park's president. The park relied too much on the founder's old formula and wasn't modernizing. Between Edward Tilyou's death in 1944 and 1959, the park had only purchased two adult rides, the C-Cruise and Scrambler for the 1948 season. In 1959 a Tilt-a-Whirl replaced the Zoo in the Pavilion, and a Round-Up centrifugal ride replaced the Human Pool Table for the 1960 season. It would be the final season for the ancient Whirlpool, which would be replaced by a Paratrooper ride the following year.

Coney Island began to change by the late fifties. Many of the old timers, who took pride in their ride or food concessions, retired or sold out. New owners ran their rides until either they broke down or were declared unsafe by city inspectors, and they looked shoddy with their paint peeling. While ride prices increased substantially during the 1950's, operators took advantage of summer weekend and evening crowds by doubling and even tripling prices. Drink and food emporiums offered worse food and higher prices with each passing year. Businessmen treated their customers as suckers with no place else to go. But as more of their core customer base bought automobiles, they discovered plenty of alternative places to spend their leisure time with a lot less hassle.

With Robert Moses', the City Parks Commissioner, desire to eventually rid the area of its fun zone, the city did little to maintain the area. The condition of Coney's streets, especially the Bowery, was appalling. In a sense it was a conspiracy among city officials to accentuate the fun zone's run down look which in turn would discourage attendance and drive the remaining owners out of business. By the end of the decade the physical differences between Steeplechase's well kept property and the rest of Coney Island was glaring.

Another natural disaster struck Coney Island and Steeplechase on Monday September 12, 1960, when heavy surf driven by the approaching Hurricane "Donna" and aided by high tides, came into the park. The Pavilion floor was covered with two feet of salt water, and all the cellars and pits were flooded. With 15 electric motors damaged, the park closed two weeks early. It was unfortunate that the profitable Pfizer Chemical Company's annual outing since 1947, where they rented the entire park except the pool area, had to be canceled. Damages were $35,000.

Changes in the ride mix were obviously having some effect on park attendance during the 1961 season. On July 19th the park ceased selling tickets after the park was only open two hours for the first time in history. There were 8,800 paying customers in the park grounds, when normally the park was lucky to see several thousand customers during the ten hour day. And on August 16th, Steeplechase recorded 18,000+ customers; the largest fully paid crowd in history. It would be a very good season, but business would decline in subsequent years.

It was unfortunate that the 1961 season was the final one for the Stage and Insanitarium in the Pavilion of Fun. Perhaps the show was antiquated, but the brutal beating of an elderly employee as well as the changing attitudes toward manhandling any person, yet alone a woman, was the nail in the coffin. On August 19th six white young men took offense at being separated from their two girls via the use of an electric cattle prod. The two girls also resented being twirled around over the blow-hole to the laughter of the audience seated in front of the stage. A fight broke out which sent Charles "Indian" Booth to the hospital with a fractured collar bone and a lacerated forehead that required twelve stitches. He went into a coma four days later, but later recovered.

The only third generation member of the Tilyou family who took a serious interest in Steeplechase Park was Frank's son, Ned (Frank F "Ned" Tilyou II). Ned, who was raised in Arizona, moved to Brooklyn in 1962 to become the eyes and ears of his father, and to prepare for the day when his generation would run the park. He wasn't the first of his generation to work at Steeplechase for his older cousin George III had leased some stands in the Pavilion to earn some spending money shortly before his father died in 1958.

In 1962 Frank Tilyou formed a partnership with his son called the Frank Development Company. In order to make room for their costly but jaunty gas-powered car ride, he ordered the Frolic moved to the location of the Express Train platforms and the Silver Streak moved to the old Frolic location. The Express Train rolling stock and track were basically given away to make room for the Go-Karts. A Roto Jet ride was placed in the Pavilion where the stage had been.

When the Seattle World's Fair closed, Frank wanted to bring all of its rides to Steeplechase and place them in the under-utilized pool area. Marie was against it. He offered to buy out everyone's interest in the park in order to expand it, but Marie wouldn't sell because she thought that her kid brother would go broke doing it.

The Tilyou family was dismayed in 1962 when the Huber family told them that they wouldn't renew the lease and that instead they had decided to sell. Fortunately George C. Tilyou had anticipated this event at the start of the park and wrote in the contract that he would have the right of first refusal in the event of sale. While the price would be steep at a time when Steeplechase really couldn't afford it, they had little choice. For without the property, they would have had no maneuvering room to turn the park around. Since they were anxious to avoid a real estate commission on the sale, they had to act before the property was officially listed. Still it took awhile for the Huber family to set a price. And when they did in March 1964, Steeplechase agreed to pay $800,000 with 10% down.

It had become downright dangerous to visit Coney Island during the early 1960's because of its proximity to low income housing complexes which had become breeding grounds for rival gangs of young toughs. While Steeplechase's new and more exciting rides attracted teens and children, those who arrived by rapid transit at the BMT terminal at Surf Avenue and Stillwell would have to dash 1000 feet to the Steeplechase gate through hostile territory. Boys were sometimes "shaken down" for their money and even beat up by young thugs, and groups of girls were so harassed that their day was spoiled. While Steeplechase was a fenced oasis of cleanliness and inexpensive fun, the rest of Coney's fun zone was filthy and noisy and a place where ride operators and food establishments gouged the public.

Steeplechase itself wasn't immune to the rising crime problem during its last two years of operation. While they thought that their prices would keep out the worst elements, increasing numbers of Coney Island blacks and Puerto Ricans entered the park. For the first time in years a Puerto Rican customer pulled a knife on a park employee, and vandals damaged the Go-Kart ride along the Boardwalk. Employees were on edge and their was concern that the July 1964 race riots in Brooklyn's Bedford-Stuyvesant area would spill over into Coney Island.

The Ravenhall Baths fire occurred on the night of Sunday April 28, 1963. The nine-alarm fire that was fought by 400 firemen with 75 pieces of fire equipment wiped out two square blocks on the west side of Steeplechase Park. Flames that shot over 100 feet into the air showered sparks over thousands of nearby wooden buildings. Fire fighters were assigned to a wide area to prevent additional fires from breaking out. As the flames spread to within a few feet of the park, some 60 employees manned fire hoses and formed a bucket brigade to wet down the roller coaster and other equipment.

Management, aware that their ticket prices per ride was substantially less than ride prices outside the park, changed its ticket policy for 1962 and 1963. Each ride was assigned a value of so many ticket punches. Old time loyal customers didn't like the new arrangement and attendance lagged. The change back to the old ride policy saved the 1964 season.

Season Bathing at the pool ended at the close of the 1963 season. While the operation was fairly profitable, the Board of Health had been demanding a new an expensive filtration system since 1960. With the uncertainty of the status of the leased Huber property where the pool stood, management decided not to spend the money. Members thought that the decision was due to racial pressure to admit "coloured" people, but in reality it was just a business decision. While the pool wasn't opened during the 1964 season, for appearances it was filled to capacity.

Frank S. Tilyou, the last of the founder's sons died on May 7, 1964. That left only his sister Marie, the richest of the Tilyou clan, in charge of the park and chairman of the board of directors. The four voting shares were now controlled by four women; Frank's widow Nickie, George's widow Adele, Eileen McAllister and Marie Tilyou. The woman each had their own agenda in their thinking for the park's future. Marie was unmarried and had no children. Eileen and Adele's children weren't interested, but Nickie might have wanted it if she could have acquired it for her two sons.

Marie faced two major problems - decreasing business as the area's crime worsened, and looming on the horizon, the next generation of indecisive squabbling Tilyou heirs if no one was truly in charge. It is hard to say which Marie feared the most. When she announced in August that she would close the park and sell Steeplechase Park, members of Coney Island's Chamber of Commerce were aghast.

Steeplechase closed permanently at 7:35 P.M. on September 20, 1964. The closing ceremonies in the Pavilion was attended by all current and past employees, Tilyou family members and important friends of the park. It was a sad an emotional night for most, an end of an era. After the speeches they played "Auf Wiedersehen," "No Business Like Show Business." and Auld Lang Syne." At the end of the final evening's closing ceremony in the Pavilion of Fun, they tolled two bells for the sounding of the years. "As the bells tolled the electrician on duty walked along the massive switchboard pulling, one paddle switch after another, so that by the last stroke the Pavilion was in brief darkness, after which he turned on some stringer lights to guide out any straggling patrons."

Marie Tilyou sold the Steeplechase property in 1965 to Fred C. Trump, a real estate developer, for $2.5 million. The first thing he did was sell the low capacity Steeplechase ride to an amusement park in Florida. They faced with the possibility that the beloved Pavilion of Fun might be declared a historic landmark, he acted quickly and demolished the building in September 1966. Ironically Trumps plan to build high-rise low-income housing on the site never materialized and the vacant land was sold to the city of New York for $4,000,000 to build a proposed park which also never occurred. Fortunately the Parachute Tower, too expensive for the city to demolish, survived and even operated through the 1968 season. Today the only structure that marks Steeplechase's place in history is a lone parachute tower that stands as a sentinel of a hopefully not forgotten era.

I would like to thank Michael Onorato for transcribing his father's diaries from 1928 - 1964. It provided much insight into the park's operation during the years that James Onorato was Steeplechase's General Manager. Without his help I never would have understood Steeplechase's final two decades.