Coney Island - First Steeplechase Park (1897 - 1907)

Revised April 1, 1998

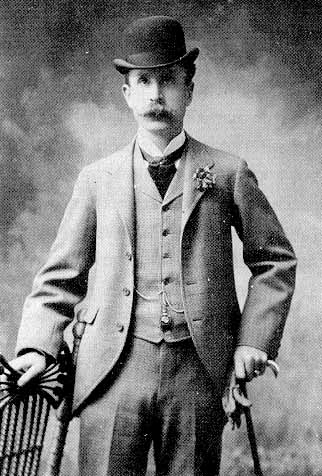

George Cornelius Tilyou, Steeplechase's founder, was born in New York City in 1862. When he was three years old his parents, Peter and Ellen Mahoney Tilyou, leased one of the huge 300 foot wide ocean front lots for $35 per year. On it they built the Surf House, a place serving food and renting bathing attire to visiting families. Thanks to Peter's father's political connections as a recorder in New York City, Surf House prospered and it and Coney Island became a favorite resort for Manhattan and Brooklyn city officials and their families.

George was a born promoter, even as a child. During 1876 when Coney Island was full of Midwest tourists who had come east to see the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition and wished to see a real ocean, George sold them cigar boxes full of "authentic beach sand" and medicine bottles of "authentic salt water" for twenty five cents each. His instincts, that gullible tourists would pay for something of no value if it had a price on it, proved correct as he earned $13.45 for his first day's endeavor. It seemed a fortune to a fourteen year old boy and he promptly retired with every intent of seeing the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition with his own eyes.

Instead he took his profits and invested in a horse, borrowed another, and using driftwood constructed a makeshift stagecoach. The following season with a better vehicle he began transporting day-trippers from the boat landing at Norton's Point on Coney's west end to Culver Plaza in the middle of the island. Of course he encouraged his passengers to stop off at his father's Surf House as they passed. By the end of the season he owned six horses and two stagecoaches. His success attracted the attention of political boss John Y. McKane who decided to sell a franchise for the route. George saw what was coming and promptly sold all his assets while he was ahead.

After growing up in Coney Island in the family's restaurant and bathhouse business, he decided in 1879 at the age of seventeen to stay and enter the profitable real estate business. Although at the time title to all land was firmly held by the town of Gravesend and was not for sale, there was a brisk and piratical traffic in leases and sub-leases. For example, it was common knowledge that one large lot on Ocean Parkway that was leased by one of the town's corrupt commissioners for only $41 per year, was sub-leased for $1000 per year to a woman who in turn leased part of her one-eighth for $4000 per year. For a budding young realtor who knew everyone, young Tilyou was netting $250 per month working out of an office constructed out of two attached bathhouses. His younger brother Edward became his partner.

However, the real estate business bored George and he sought to become a showman by providing entertainment for the thousands of tourists that visited the Island. In 1882 when he was twenty, he and his father Peter built Coney Island's first theater, Tilyou's Surf Theater, along an alley that bisected the walk streets between Surf Avenue and the ocean. Performers like Weber & Fields, Sam Bernard and Pat Rooney appeared on its vaudeville stage. To make sure that audiences could easily make their way through a cluster of lager-beer saloons, clam bars and bathhouses, they paved the alley with wooden planks and called it Ocean View Walk. Since it was reminiscent of a notorious Manhattan street that had become synonymous with theatrical bright lights and immoral gaiety, it was dubbed "The Bowery" by Mrs. Newton, the mother of McKane's chief lieutenant. The name stuck.

When a law was passed permitting the sale of Gravesend's common lands, George abandoned his dream of becoming an entertainment magnate for a lucrative career in real estate. He rented out his theater, concentrated on real estate and by 1887 he had become quite successful. But the Tilyous, both father and son, were reformers and were opposed to boss McKane's corrupt rule on both moral grounds and on the principle that it was bad for business. As a stubborn businessman George realized that McKane, by appointing ruffians and rouges as justices of the peace, by winking at prostitution and gambling, and by plundering the community by taking a cut of the action, he was offending decent folk everywhere. Tilyou wanted those decent folk as his customers.

So when a New York state Assembly committee in 1887 investigated the crime and corruption at Coney Island, George stood alone and was the only Coney Island resident who dared to blow the whistle on John Y. McKane by singling out the most corrupt of McKane's henchmen. The area's crooked police chief ran the island as his private fiefdom, passed out political favors, allowed criminal friends to set up shop along the Bowery, and made important allies by leasing and selling the town's public lands at low prices to powerful businessmen who became indebted to him. When the politicians declined to prosecute McKane, Tilyou was forced to close his real estate business. His parents suffered too as McKane using guile and strong armed tactics cheated them out of nearly all their property. But when McKane was finally convicted and sent to Sing Sing in 1894 for voter fraud and fixing elections, George Tilyou returned. With Coney Island annexed by Brooklyn, George became the justice of the peace as a reward for cooperating with the Brooklyn reformers.

| George C. Tilyou as a successful young man. |

In 1893 George married Mary O'Donnell, and for their honeymoon they went to Chicago to see the World's Columbian Exposition. This was the world's fair that introduced a "midway" containing rides, shows and concessions separated from the rest of the largely industrial oriented fair. George was looking for an interesting amusement that he could bring back to Coney Island. Once he gazed upon George Ferris' gigantic 250 diameter steel wheel that suspended 36 cars, each holding 60 passengers, he knew that he had to buy it. It was a money maker that when full held 2160 people who each paid fifty cents to be transported high in the sky for a view of the fair as the ride rotated slowly. Unfortunately for George, the ride had already been sold to the promoters of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition to be held in St. Louis in 1904.

George instead borrowed money and ordered a smaller half sized 125 foot diameter wheel from the Pennsylvania Steel Company, with 12 cars, each holding 18 passengers. When George returned from his honeymoon, he leased a plot of land at the Bowery and W. 8th Street near the Iron Tower and erected a sign that read "On This Site Will Be Erected the World's Largest Ferris Wheel." On the strength of this "whopper", George was able to sell enough concession space around the wheel to pay for the wheel's delivery during the Spring of 1894. Once it was erected and covered with hundreds of incandescent lights, it immediately became the biggest attraction at Coney Island. For ballyhoo, he put his pretty blonde haired sister Kathryn in the change booth as cashier and her wearing an evening dress with her mother's diamond necklace in plain sight. For effect two big burly men were hired to stand beside her, as if they were bodyguards protecting her expensive jewelry.

| Tilyou's Ferris Wheel was 125 feet in diameter and its 12 cars each held 18 passengers. |

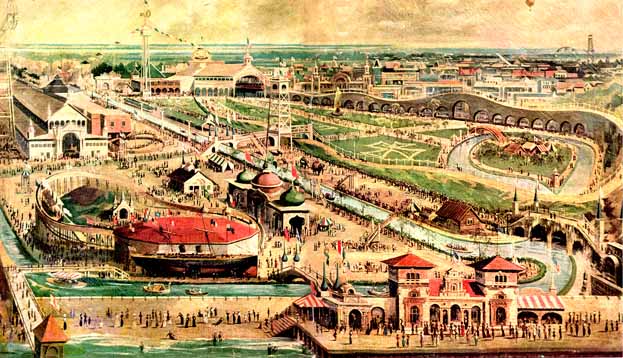

George had other attractions scattered all over the West Brighton section of Coney Island. He had an Aerial Slide, an imported Bicycle Railroad and the Double Dip Chutes. It never occurred to him to move them near his Ferris Wheel until Captain Paul Boyton opened his nearby enclosed Sea Lion Park in 1895 and charged an admission fee to enter. Once George Tilyou understood the amusement park concept, he looked around for an attraction that would do for him what the Shoot-the-Chutes ride had done for Boyton. Since the most popular sport at the time was, by all odds, horse racing and Coney Island was crowded with people who attended the races at Gravesend, Sheepshead and Brighton Beach during their six month seasons, he was excited when he heard of J.W. Cawdry's mechanical race course. He bought the rights to the British inventor's flawed ride but improved it beyond recognition by the time he opened Steeplechase Park on an ocean front beach plot of slightly more than 15 acres. While he owned outright nearly ten acres on the east side of the plot, he leased an additional five acres on the west side from the Huber family.

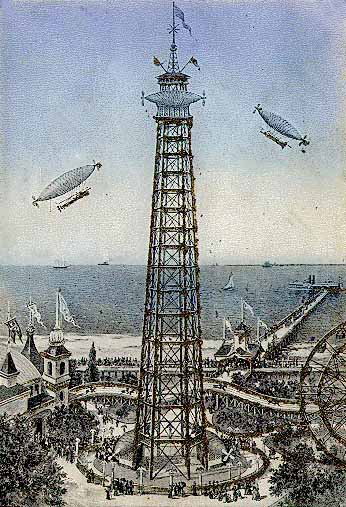

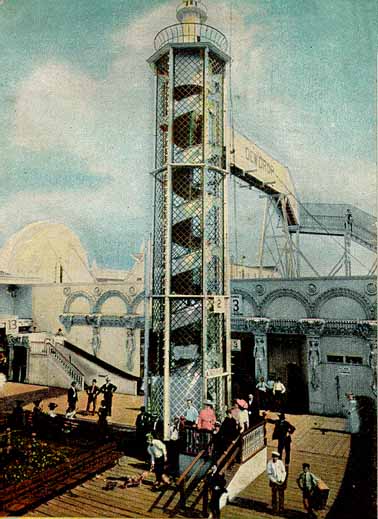

| The Airship Tower with the Steeplechase track and the Steeplechase Pier in the background. - 1905 |

His premier attraction, dubbed the Steeplechase Horses and costing $41,000, was an undulating, curving, metal track over which large double-saddled wooden horses ran on wheels in an imitation of a real horse race. It was a gravity driven ride where six horses running along six parallel 1100 feet long tracks coasted down inclines and soared up the next hill by momentum. The course crossed a stream bed, and over a series of hurdles. Tilyou also gave his ride realistic touches with attendants dressed as jockeys, buglers to announce the race start, half and quarter mile posts and a finish wire at the end. Unlike actual horses races where the lightest jockey was more likely to win, the heaviest riders usually coasted through the finish gate to victory.

| The Steeplechase ride was a simulated horse race along a 1100 foot long course. |

Tilyou added other attractions. He had naphtha-powered boats cruising on Venetian canals until 1905, a miniature steam railroad and convinced LaMarcus Thompson with a $40,000 guarantee to build a Scenic Railroad (early roller coaster) at Steeplechase Park. A large salt water swimming pool was constructed behind his family's bathhouse. He also had the largest ballroom in New York state. It featured four bands each taking turns providing music for the dancers. He charged twenty-five cents to enter his park and visitors could enjoy his attractions as often as they liked. He learned early that an enclosed park had the advantage that it effectively eliminated criminal and sordid elements that roamed Coney Island and preyed on the innocent visitor.

George Tilyou knew that he needed to make constant additions and changes in his park to keep it successful. In 1901 he attended the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo to scout for attractions. The attraction that caught his eye was an illusion ride called "A Trip to the Moon" that was operated by two partners Frederic Thompson and Elmer (Skip) Dundy. The two men were making a fortune at the Exposition.

"A Trip to the Moon was housed in a large round building. Sixty passengers would board a large raised winged spaceship where they sat on steamer chairs on an open deck. They could watch the ship's liftoff and flight to the moon through portholes in the walls and floor of the room. Scenes painted on movable canvas screens gave the riders the illusion of liftoff from the fairground, flight past Niagara Falls then up into space away from a shrinking Earth. The ship slowly rocked and wind blew from hidden fans while cables and rods linked to motors made the ship's huge wings slowly flap. En route to the moon, travelers encountered a fierce electrical storm with thunder, lightning flashes and whistling wind. The ship would then approach the moon and fly over its canyons and craters before making a landing. The debarking passengers, now within the crater of an extinct moon crater, were greeted by Midget "Selenites" with spiked backs. They were led down a long illuminated avenue filled with toadstools and fantastic trees to the City of the Moon and beyond the moat to the castle of the Man in the Moon. Finally moon maidens escorted the visitors into the green cheese room where they would offer them tasty pieces of cheese off the walls. Passengers returned to Earth via a swaying bridge.

Tilyou approached the owners and offered them 60% of the net profits if they would bring their attraction to Steeplechase Park. Since they didn't have another engagement until the next world's fair in 1904, they readily agreed. Thompson and Dundy also brought with them another illusion cyclorama called Darkness and Dawn and a ride called the Aerio Cycle which featured two small Ferris wheels on each end of a giant tether. This renamed ride, the 235 foot long Giant See-Saw, would lift passengers nearly 170 feet into the sky.

| Steeplechase Park in 1903. In the foreground was the boardwalk entrance. Just beyond visitors could board naphtha-powered launches on the Canals of Venice. At the bottom right was the French Voyage and behind it was the Scenic Railway. The Giant Sea-Saw was on the high tower at the far left, and the adjacent Stadium probably housed the cyclorama, "A Trip to the Moon." The Arena, the large building in the background, was the starting point for the Steeplechase horses whose 1100 foot long undulating track extended nearly to the ocean and back. |

The summer 1902 season at Coney Island was gruesome for nearly all the ride operators for it was one of the wettest in Coney Island's history. Of the 92 day summer season, rain fell on 70 days. While Sea Lion Park was doing little business, Steeplechase, thanks to "A trip to the Moon" did fine. When the season had ended Tilyou offered Thompson and Dundy a renewal on their contract but with their cut lowered to 40% of the net profits. They of course weren't pleased and within a few days negotiated with Boyton to build a park of their own where Sea Lion Park stood.

Their Giant See-Saw ride didn't fit into Thompson's vision of their park. While it was worth $40,000, Tilyou was too close-fisted to pay such a price. George suggested that they coin toss for it, double or nothing. Thompson lost the toss and the ride remained at Steeplechase. Tilyou wasn't the least upset that Thompson and Dundy decided to compete with him for he knew that more attractions installed on Coney would draw bigger crowds and more profit for everyone.

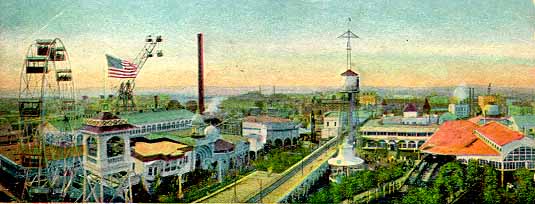

| A view of Steeplechase Park from the Airship Tower in 1905. |

While Tilyou couldn't compete against Luna Park's and Dreamland's more expensive and spectacular attractions, he understood that visitors would pay to be part of the show. His genius is that he invented five contraptions and modified a sixth to provide backgrounds for his star performers; his paying customers. These were scattered in individual locations in his park.

Visitors entering the park through the main Boardwalk entrance had to pass through the Barrel of Love. It was a slowly revolving, giant cylinder of polished wood, about fifteen feet long, through which a person by careful diagonal movement could remain erect as they passed through. But if one lost their footing, they could end up in an intimate arm and leg tangle with complete strangers.

| The Human Roulette Wheel. - 1905 |

Tilyou's other unique participatory attractions, that encouraged sexual titillation and exhibitionism, were the Earthquake Stairway, Dew Drop, Whichway, Human Roulette Wheel and Wedding Ring, later called the Razzle Dazzle and still later the Hoop-La. The later was a great circle of laminated wood suspended by wires from a center pole. Nearly 70 people could sit insecurely upon its frame while four muscular men rocked it back and forth. When a girl lost her balance her ankles would show and she would have a reason to clutch at her escort. The Earthquake Stairway featured a flight of steps split in the middle. One half would jerk suddenly upward while the other half jerked downward a few inches. The Whichway was a swing that whirled its passengers eccentrically in any of four directions, but invariably catapulted a girl into her escort's lap. The Dew Drop had patrons climb to the top of a fifty foot high tower where they whirled feet first downward in a spiral until they were thrown outward upon a billowy platform. Later he added a Human Roulette Wheel where people tried to play King of the Mountain, but if they didn't reach the top center, they were flung off the spinning platform by centrifugal force.

George C. Tilyou during the years between 1905 and 1907 was forever refining his park and its attractions. After the Canals of Venice were removed he constructed a 25 foot wide, 25 feet high pedestrian arcade from the portal at Surf Avenue to the 700 foot long Steeplechase Pier. Atop it ran electric observation cars to transport arriving steamship passengers into his park. And there was room, too, for a miniature railroad to make a serpentine circuit of nearly a mile. He retained the popular French Voyage in the circular pavilion down by the beach, Atlantis Under the Sea and the House Up-Side Down.

He remodeled the Ballroom for the 1906 season with an improved orchestra stand in the center. Above it was a cluster of lights that flooded the area with changing multi-colored lighting. The drab white statutes along the walls were replaced by one of gaily painted Spanish dancers. Behind the Ballroom, he constructed a miniature reproduction of Manhattan's Flatiron building. The unwary visitor encountered a tempest of man-made wind that blew off hats as they turned the corner. Part of the old Dante's Inferno Building was torn town and replaced by the Cave of the Winds, and a Fads and Fantasy Building was constructed to house several novel new amusement devices.

The Limit Building featured a new automobile illusion. A full-size motorcar started its journey at full speed then suddenly appeared to stop. At that point, with its wheels still spinning, the scenery began to mechanically scroll in the background and gave it the illusion of traveling forwards. Suddenly a pedestrian appeared in its path and apparently was struck with full force, much to the horror of the spectators. Perhaps it was an educational exhibit to show the naive audience the consequences of challenging a motor car's right of way.

Children weren't neglected either. There was a new pony track featuring Shetlands of which three were pure white. And the park purchased a new carousel of the flying horse type for $25,000.

For the 1907 season, Tilyou built on the site of the old Limit Building, a new structure 120 x 85 feet, and 50 feet high called the Monte Carlo Building. Inside was a 25 foot diameter Human Roulette Wheel where patrons could play King of the Mountain. In a nearby area of distorted mirrors where people could grin at their funny reflections was the Jumping Floor. Its sudden movement where they stood was a surprise to many who upon springing from the contraption, plunged head first into cyclonic gusts of his St. Augustine Tower. On the balcony above was a Human Zoo. A narrow spiral stairs lead down into a cage. And when the unwary visitor was trapped, he was offered peanuts and subjected to monkey talk by the crowd gathered outside the cage.

| The Drew Drop spiral slide. |

One attraction in 1900 that proved the gullibility of a curious public was dubbed the "The California Red Bats." As Tilyou described it, "I built a flight of six steps up to a table, placed a box in this and in the box put three broken bricks [brickbats]. Then I charged ten cents a look at these bricks. Everybody was curious and everyone looked but nobody told what they saw. Naturally the curiosity spread like the measles and in that season 300,000 people came to see an exhibit that had cost me precisely $5. It was Tilyou's prank to see if the American public wouldn't mind an occasional joke on themselves, if it were a good natured joke.

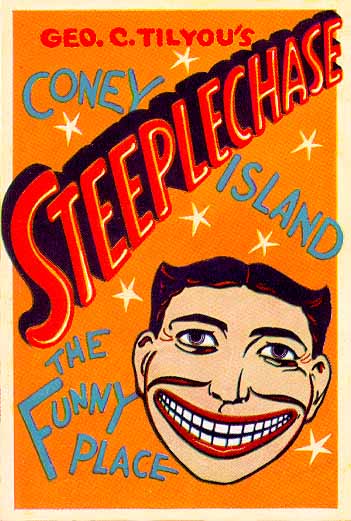

While Steeplechase's attractions were slightly more low class and vulgar than the competition, the public was quite anxious to patronize Tilyou's park. Perhaps his huge celebrated Steeplechase Funny Face grinning frightfully with its forty-four teeth (12 more than normal) exemplified the mood of the park's attractions. It was grotesque, a diabolical jester that hinted at a promise of irresponsible hilarity visitors hoped to experience within. And they could experience it all by purchasing a combination ticket; 25 attractions for 25 cents.

| Steeplechase Park's trademark logo. |

Steeplechase's Fiery Demise

Unfortunately not everything survives and Tilyou's first Steeplechase was no exception. A lighted cigarette carelessly thrown into a waste receptacle in the Cave of the Winds attraction caused a long smoldering fire to break out at 4 A.M. on July 28, 1907. A night watchman on patrol noticed a thin line of smoke coming from the building. As he entered the Cave, a cloud of smoke and flame burst out towards him. After he ran to the signal box and turned in the alarm at 4:18 A.M., it only took a minute or two for Engine Company #144 to arrive from their station located across the street. Meanwhile Tilyou, who hadn't left the office and was busy with his daily receipts, rushed to the scene and tried to fight the fire himself. By then the fire had eaten through the sides of the wooden building. Battalion Chief Rogers then ordered another alarm sent, which brought in nearby engine companies #146 and #153. By then all of Coney Island was aroused and a crowd assembled.Residents, aware of an impending disaster much like earlier fires that had swept the Island, ran for every hotel and pavilion to warn other to flee for their lives. In less than thirty minutes Steeplechase was doomed. The light breeze from the southeast stiffened and flames spread quickly towards the Bowery. Then they turned west and in a short time burned all of the attractions at the north end of the park. The Steeplechase horse ride, the $100,000 electric plant and the big Post Office building, once Tilyou's residence, burned, then the wind took another turn and began to wipe out most of the park's 25 attractions. It quickly became obvious that the spreading flames could not be checked by Coney Island's inadequate fire fighting equipment.

A friend of Tilyou's, noticing that Tilyou's home in the park was threatened, alerted Fire Chief Blaus and begged him to send men and hoses to that section. "Chief, " he said, "this man has lost all his property. Are you going to let him lose his home, too." That appeal moved the Chief and his home was saved. Despite fire fighter's attempts to control the fire, a third alarm was sent.

Once the fire broke out onto the Bowery at the Steeplechase entrance, fire fighters could only hope for a miracle. People sleeping at George Ferris' Kensington Hotel barely awoke in time to escape with their lives. The concert hall owned by Louis Lent opposite it along the Bowery was the next to burn. Lent ran into the burning building and pulled the cash register containing $1000 out into the street, but when he turned around it was gone. Fire raced for the beach, destroying several big moving picture and bathing pavilions and threatening those who had sought safety there. When it reached the south side of Oceanic Walk it wiped out the newly built Drop the Dips scenic railway. Finally the winds shifted towards the north and the fire went around the Trocadero Hotel. Within two hours time the fire, working along the south side of the Bowery reached the mammoth bathing pavilions owned by Louis Stauch and George Hoch at the its eastern end. It was Stauch's large brick dance hall, and the tin wall at the Cannon Coaster that finally halted the fire and prevented it from spreading east to Feltman's Restaurant and Dreamland. After the fire was extinguished, police set up lines to prevent looting. Hundreds of woman and children who lived in cheap rooming houses in the scorched area were homeless.

Fortunately only two people were seriously injured in the four hour blaze. Fireman Messina was injured and hospitalized when he was struck on the head by a falling beam. Also Sylvester Mead, a twelve year old boy, who was sleeping in a small shanty was severely burned but survived. More than a dozen others suffered minor burns.

George Tilyou's calmness made him a hero to both friends and enemies. He went to his house just as the fire was being brought under control, changed his smoke begrimed and water soaked hat for a more presentable one, and journeyed over to the Church of Our Lady of Solace one block away to attend 7 A.M. mass. Afterwards instead of sitting down and bemoaning his loss, he set to work on the hot ashes to build another amusement park. Although only the Ferris Wheel, giant See-Saw wheel, swimming pool, beach bathing pavilion, Upside-Down House, pier and one big tower survived, he sent an order to Brooklyn for a large order of lumber. He was also kind to several of his tenants like Hoch who, like him, suffered a loss. He suspended their rents.

Tilyou, the consummate showman erected a fence and posted a sign reading.

"To inquiring Friends: There was a lot of trouble yesterday that I have not had to-day, and there is lots of troubles to-day that I did not have yesterday." - Geo. C. Tilyou

On this site will be erected a bigger, better Steeplechase Park.

Admission to the Burning Ruins - 10 cents.

Many loyal patrons bought 10 - 50 tickets to see the ruins out of deep appreciation of Tilyou's loss.

Tilyou released a statement to reporters to counter rumors that Steeplechase was entirely destroyed. "Steeplechase , although scorched a little, still has 25 attractions for 25 cents. I have completed the broad walk from Surf Avenue to the unburned part of the park and soon another will be built from the Bowery entrance. Five acres are OK. The swimming pool will be sacrificed and I'm building a human roulette wheel in its place. The tiered balcony offers a view of the ludicrous working of my latest invention. An army of 500 workers are at work, and by next Saturday, we will reopen. Most of the best features of Steeplechase still remain. I want to correct the notion that Steeplechase was wiped off the map." He also corrected the impression that with, a cold and rainy spring, he had a bad season. He assured them that it had been his best season to date.

The total loss was $1,404,000 of which about one million dollars was sustained by the uninsured park. Tilyou also figured that he lost an additional $300,000 in profits for the remainder of the season. Luckily $12,400 in cash survived in the park's safes. Some of the other larger owner's loses included Kojan's Pavilion on Ocean Front Walk - $50,000; Drop the Dips scenic railway - $50,000; Louis Lent's Concert Hall - $50,000; Arkanau Brother's pavilion - $60,000; George Hoch's Hotel - $30,000; Kensington Hotel - $30,000; and Louis Stauch's bathing pavilion - $65,000. There were more than a several dozen small businesses like Scarana's Italian Restaurant that suffered losses of only a few thousand dollars.