Coney Island - Luna Park

Revised May 1, 1998

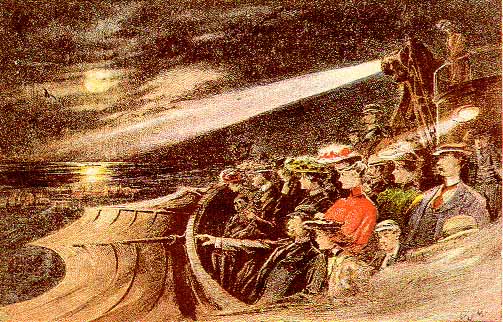

Frederick Thompson and his partner Skip Dundy made a name for themselves at

the Pan-American Exposition held at Buffalo, New York in 1901. They created

and operated a cyclorama show called "A Trip to the Moon" where the public

was transported on an imaginary flight to the moon in an enormous ship with

huge flapping wings. The voyagers entered the building's sumptuous lobby

and to the craft's dock which was fitted like a railroad station's waiting

room. From there they could glimpse "Luna," a brilliantly lit green and

white cigar-shaped craft, lying quietly in the moonlight. It was the size

of a small lake steamer with colossal red canvas bat-like wings outstretched

above a large cabin set in the middle. Thirty passengers came aboard the

companionway onto its deck where they were seated in steamer chairs or could

stand and lean on the rail. A gong sounded. "Luna's" huge wings began to beat the air with slow strokes, and the ship's deck, balanced on gimbaled bearings began to undulate. Then there was a rush of wind as the ship, straining on its heavy cables, appeared to rise into the air. The painted views of the Exposition grounds began to drop and was replaced by thousands of blinking lights of the city below. As it soared higher into space, they could see the Earth as a globe that rapidly diminished in size. Although the scenery was painted on movable canvas, it was an effective illusion of soaring off into space.

Suddenly everything darkened almost to complete darkness. Lightning flashed across the sky, thunder rolled and there was a fierce rain on the awning overhead. "We are passing through a storm," shouted the captain, "we are quite safe." After the rain slackened and the stars came out, it was morning.

When the ship finally reached the moon and dropped through a sea of sunlit clouds, it flew past canyons and craters stained red, yellow and green. It then slowed, and veering right, landed in the crater of an extinct volcano. The passengers were met by midget moon men, Selenites, whose backs had rows of long spikes. They sang refrains of "My Sweetheart the Man in the Moon," then escorted them through stalactite caverns, across chasms spanned by spidery bridges to the underground city of the Moon. There at the entrance of a broad avenue lined with the illuminated foliage of fantastic trees and toad stool growths, were the walls of a castle beyond a moat. They were led to the throne room where there were seats for the Earth visitors. Bronze griffins flanked the sides where the "Man in the Moon," a giant, sat on his splendid throne. On the stage in front was the Geisler electric fountain that displayed all the colors of the spectrum through its cascading water pulsing in a rhythmic dance.

As the visitors departed moon maidens in the green cheese room offered them tasty pieces of their cheese. Of course back then, everyone was certain the moon was made of green cheese. The moon tourists walked out through the mouth of a mighty "moon-calf" into the park's daylight.

| Thompson & Dundy's Trip to the Moon ride was a rousing success at Coney Island. - 1902 |

There had never been an attraction even remotely like the Trip to the Moon. It was revolutionary in amusement entertainment and engineered to amaze the unsophisticated public of the day. It didn't matter that its scientific principles were outlandish for it attracted attention far and wide. Many notables of the day, who visited the attraction, included Senator Chauncey M. Depew, Thomas Edison, Secretary of War Elijah Root and President William McKinley on the evening before he was assassinated at the fair. Its popularity was so great that they offered thirty, 20 minute trips daily and doubled the seating capacity by October. The ride, which charged fifty cents, twice the price of other attractions, was experienced by over 400,000 people before it closed on November 2nd.

George Tilyou, owner of Steeplechase Park, who had gone to the Exposition to obtain rides and attractions for his park, was impressed. Their show was different from previous shows where people sat around bored while they watched a battle. Instead it offered movement and action. He wanted Thompson and Dundy to bring their attraction to his park the following season, but the partners weren't interested at first. After the exposition closed they prepared their show for storage to eventually take to the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904 in St. Louis. While Dundy left for St. Louis to bid for their concession, Thompson went to New York City. There he negotiated with Tilyou who offered them 60% of the net profits if they would bring their attractions to Coney Island for the 1902 summer season. Dundy, who didn't like the deal, traveled to New York to scuttle it, but Thompson changed his partner's mind. They also brought their other attractions with them; a show called Darkness and Dawn, and the Aerio Cycle, a double Ferris wheel whose wheels were on opposing ends of a seesaw.

"A Trip to the Moon" was a rousing success at Steeplechase with 850,000 people experiencing the unique ride. Despite one of the dreariest and rainiest summers on record (rained 70 days out of 92 days), Steeplechase was the only park that was drawing crowds and making money that summer. At the end of the season George Tilyou offered to renew Thompson and Dundy contract, but only offered them 40% of the net profits instead of their customary 60%. Whether it was a calculated move or not by Tilyou to increase competition and business at Coney Island, he knew he couldn't keep the talented pair in his employ for long.

The two disgruntled partners decided to take advantage of Boyton's economic misfortune after that rainy summer, when they were offered a 25 year lease on Sea Lion Park. They also leased the land in front of it seaward to Surf Avenue, where the Elephant Hotel had stood until the 1896 fire. They had an initial 22 acres to build their park.

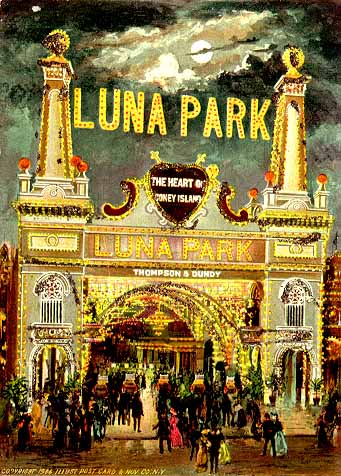

Thompson, who had previously worked as an architectural draftsman, drew up plans for his park that would give his "Trip to the Moon" ride and his planned "Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea" ride (a submarine ride to the polar regions), the proper setting. In his private rebellion from the traditional Beaux Arts architectural style of the day, he choose an Oriental theme using spires and minarets wherever he could to achieve a restive yet joyous effect. Whereas in traditional parks one lone tower would act as an exclamation point to its coordinated over-all design, Thompson's genius was that he let his towers proliferate at random. His world was a forest of towers and minarets that gave his park a look of other worldliness. He would add more spires to his park each season, until he had 1221 red and white painted towers, minarets and domes. His architectural style was meant to lure people with its novelty by day and to furnish a picturesque fairyland profile by night when it was illuminated with 250,000 electric lights. The park could turn night into day in its topsy turvy world. While it has been widely written that Thompson named the park after his partner's sister, Luna Dundy, it is clear from Luna's pre-opening brochures that it was named in honor of the Airship Luna in their premier attraction.

| Luna Park's original main entrance. - 1903 |

He built the park around the lagoon and incorporated the previous park's successful Shoot-the-Chutes ride, plus its dancing and swimming facilities. There were plenty of new attractions and to please his partner, who was circus crazy, he planned a tremendous program of aerial and animal acts. By carefully spacing his most outstanding attractions, he sought to keep the crowds moving. And by spreading an icing of free acts, he schemed to keep them contented.

Construction of the park under the supervision of Henry Riehl began in late November. A workforce of over 700 carpenters, electricians, artists, blacksmiths, painters, inventors, illusionists, artisans and laborers worked both day and night to turn Thompson's dream into reality. Most of the heavy hauling, including moving the key components of their Trip to the Moon ride from Steeplechase to its new location near its Surf Avenue entrance, was done by the park's elephants. Unfortunately a female elephant named Topsy became vicious and killed one of the trainers after he fed her a lighted cigarette.

Only Thompson's showmanship could convert a tragedy into a spectacle. They decided that the vicious Topsy had to be put to sleep. Although it was winter and the park was under construction, Thompson advertised that on a particular Sunday they would execute the elephant by feeding her poisoned carrots laced with 400 mg of potassium cyanide. Several thousand spectators, each hoping to be thrilled by the elephant's death, filled the arena to capacity. But the thrill never came as the management probably knew; the supposedly poisoned carrots would have little or no effect. Since publicity stunts needed to be milked for all they're worth to keep the crowds returning, Luna Park announced that Topsy would be electrocuted the following Sunday January 4, 1903. They had planned to hang her, but animal rights groups protested. Record crowds returned to witness the gruesome event that resulted in her death in less than ten seconds. Edison power company workers hooked up an electrode to her right front foot and one to her back left, then on signal turned on the current. Smoke rose from her hide as she convulsed, then seconds later she toppled over, dead. Thompson preserved two of the elephant's feet and part of her hide for an office chair.

The park would cost them $700,000 to build. Dundy figured that they could raise $220,000 and build a less ambitious endeavor. Thompson, who was a born promoter proclaimed, "What's $500,000? Let's go ahead with the plans, and when the cash gives out you can run up to Wall Street and corral the other half-million. Skip Dundy found investors among the Coney Island racing crowd, He persuaded Bet-a-Million Gates, the steel man, and George Kessler, the champagne salesman, to make heavy initial investments. And when the time came to raise more money, they did run to Wall Street to find more investors. Even so, there were times during construction when the till was nearly empty. In fact, the day they opened, Thompson and Dundy only had twelve dollars between them, barely enough to make change at the ticket booths. Their clothes became so worn and tattered, that for the official opening, they had to borrow suits from their valet who had worked during the winter without pay.

The public, seeing the forest of soaring spires under construction that winter and spring, eagerly awaited Luna's opening. Posters, up and down Surf Avenue advertised its "Thirty-Nine Supreme, Stupendous, Spectacular, Sensational Shows! By day a Paradise - at Night Arcadia." It was billed as the "New York World's Fair" and featured attractions representing many of the world's exotic locales.

The grand opening was on May 16, 1903 when at eight o'clock in the evening, 250,000 electric lights were switched on. After a short dedication ceremony, the five-lane gate was opened to an endless stream of visitors. They filed past beautiful woman ticket sellers dressed in evening attire and a red hats who performed their job aboard five Roman chariots. The admission fee was ten cents (attractions and rides extra), but when they eventually ran out of change later that evening, they let people in for free. By 9:20 P.M. the attendance stood at 43,000, and by 10 P.M. over 60,000. Their park was a success. The dazzled public, contemplating what Luna stood for, assumed it was for light.

| At night Luna Park's towers and buildings were lit by a million lights. - 1904 |

Beyond the great entrance arch, whose interior was a solid mass of lights, was a broad avenue called the Court of Honor. On the right side was Venice in New York, a recreated Venetian city with its detailed buildings and colonnades. And in front of the city was a Grand Canal spanned by an illuminated bridge and full of gondoliers propelling their gondolas along the waterway. Along the canal edge were long rows of hand-cranked "mutoscopes" that the visitor, for a penny, could see many sorts of moving pictures, a circular drum of flickering flip card images.

On the left of the broad avenue, nearest the entrance, were three giant buildings. The first was Luna's premiere attraction, A Trip to the Moon, revamped in a new building at a cost of $52,000. The centerpiece of the ride was a ship called Luna III, enlarged to accommodate more passengers. It too, attached to gimbaled bearings to impart a rocking motion, had enormous flapping wings that flapped out horizontally to prevent passengers from peering over the rail. The show had changed somewhat from its Buffalo incarnation. It rose over a panorama of Coney Island and passed over Manhattan's skyscrapers before rising into the clouds. Another change was that Senelite dwarfs lead passengers to a dragon's mouth which opened and allowed them to walk into its stomach. The way was treacherous, for the floor rocked and the walls of its alimentary canal were clammy. One felt relief as well as surprise when they found that the dragon's tail reached down to the earth and the streets of Luna Park.

The next building resembled a monster battleship with turrets, spontoons, and fighting tops bristling with protruding guns. Within the War of the Worlds building, which were shaped to represent Fort Hamilton and New York Bay, was a scenic spectacle in which miniature versions of the navies of the allied European powers attacked New York Harbor. The audience was seated in one of the batteries guarding New York. From that vantage point they watched 40 ships, the combined navies of Germany, Britain, France and Spain sail over the horizon towards Manhattan. As the battle raged, the fort's mighty guns shook the ground as they fired on positions five miles away. Sometimes an occasional vessel was sunk or disabled amidst sulfurous clouds of smoke obscuring the chaos. One lucky enemy shell surprised the audience as it partially blew up one of Fort Hamilton's bastions in a thunderous roar. But before the enemy could lay siege to the city, Admiral Dewey's American fleet intercepted them and sank every one of their ships. The show used a combination of actors and electrically controlled models, while in the background, the huge painted canvas showed the harbor and Statue of Liberty.

In the third building was Luna's Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea submarine ride to the polar regions. Outside an oily fur-clad Eskimo barker continuously announced that the great submarine was about to depart for the North Pole. Visitors descended into the bowls of the craft where they could observe through its plate-glass portholes, the miles of passing green water where strange creatures resided. There were feathery seaweed, large tenacled octopus, finned creatures of all sizes and one mermaid. At the Pole amidst open water and floating icebergs made possible by a refrigeration plant, they discovered an Eskimo igloo village with sleds pulled by dog teams. There were real seals and polar bears cooling themselves on the icebergs. An aurora borealis colored the sky. After the boat surfaced and its passengers debarked, they were guided about the city by the Eskimos.

The Court of Honor opened out onto a broad esplanade, which bordered on a lake into which boatloads of screaming passengers descended down the brightly lighted "Shoot-the-Chutes" slide. The boats upon hitting the water, bounced and became airborne for a short distance, much to the delight of its passengers, before gliding in the still lake waters. Then the boatman in the rear of the craft guided the craft to a safe dockside landing where its departing frightened children pleaded with parents to ride again. Bordering the lake was a terrace, set with benches and decorated with festoons of lights. At the lake's center was the 200 foot tall Electric Tower that was thickly studded with lights, so brilliant that it could be seen for miles. At its base were a series of cascading fountains.

Near the foot of the tower, but built out into the lake to either side, were two circus rings. that showcased frequent performances of trained animals, equestrians and clowns. Trapeze and high wire acts performed their feats at a height of nearly 200 feet. One performer, Cameroni, who with his hands tied behind his back and hung by strap clenched between his teeth, shot down along a cable from the top of the tower to the extreme end of the park. Other circus acts included LaZalle - novelty wire act; George Gilbert and his goats; Josie Ashton - Queen of Equilbrists; Hassan Ben Ali - Arab Acrobats; The Two Picos - King of Clowns; Ernest Melville - bareback jockey; and Howard - English equilbrist.

On the other end of the lake was a raised platform where Scinta's Band played. And nearby in the circular Hippodrome arena to the right of the Chutes was Carl Hagenbeck's Trained Wild Animals.

Located in a single story building to the left of the Chutes ramp was Dr. Courney's unique Baby Incubator exhibit. Inside at his nurse staffed hospital babies were displayed that were born prematurely. These tiny babies were placed in his care by hopeful mothers at a time when most hospitals didn't have incubators to care for them. He employed wet nurses so that the babies received natural mother's milk, and a thermostat controlled system that blew filtered air past hot water pipes to maintain the proper incubator temperature. These tiny sleeping babies, boys tied with blue ribbons and girls with pink ribbons, were displayed in their small crystal houses. To cover expenses he charged 25 cents to view these children and his novel method to keep them alive. Woman, particularly childless women, were the bulk of his visitors.

Around the various parts of the grounds were the Babbling Brooks where boats took passengers through simulated lakes and rivers, Japanese gardens, German and Irish villages, a Chinese Theater, Eskimo and Hindu villages, and Wormwood's Monkey Theater. A miniature railroad, pulled by a locomotive bigger than its engineer, dashed through darkened tunnels and brightly lit fairylands. In one corner, near the lake, was a quaint old Dutch windmill. Set beside it was a slippery bamboo chute with a sharp incline and many devious turns. It was wide enough for a good sized boy, and nearly 3000 boys decided to wear out their pants bottoms that opening night.

Admission to all of Luna's attractions only cost the visitor $1.95, but most patrons had an enjoyable time by only spending a fraction of that amount. The most expensive attractions cost 25 cents and they included a Trip to the Moon, War of the Worlds, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Hagenbeck's Trained Animals and the Infant Incubators. Others like the Shoot the Chutes, Wormwood's Monkey Theater, the Gondola Launches and the Japanese and Chinese Theaters were only a dime. A ride on the Midnight Express miniature railroad or the Razzle Dazzle ride only cost a nickel.

Luna's 250,000 lights dimmed and flickered out the following night when trouble at Coney Island's electric plant plunged the resort into near total darkness for thirty minutes. Its estimated crowd of 60,000 made a wild rush for the exit and many were knocked down and trampled. Meanwhile out on the streets, where many of Coney's 200,000 visitors gathered, slick-fingered pickpockets relieved many of their watches and wallets. Businesses along the Bowery hurriedly lit their gas jets before the crowds began to leave. However, places there like Stauch's and Henderson's that didn't have backup lighting lost nearly all of their business for the evening.

Luna Park was an immediate and stupendous success. It was so successful that by July 4, 1903, a day when attendance reached 142,332 paying customers, Thompson and Dundy had paid back every cent they had borrowed. By the end of the season they were rolling in money. Those who had gambled with them were rewarded handsomely. When ex-Tilyou employee, Charles Murray, the head of publicity, had enough courage to work the summer on a percentage basis with no salary, he was rewarded with $116,000 at the end of the season. He then promptly retired.

The reason for Luna Park's immediate success can easily be summed up in Thompson's philosophy and observations of his fellow man. Visitors to a seaside resort "are not in the mood, and do not want to encounter seriousness in their every-day lives, and the keynote of the thing they do demand is change. Everything must be different from ordinary experience. What is presented to them must have life, action, motion, sensation, surprise, shock, swiftness or else comedy."

During June 1904 the Sea Beach Land Company decided to sell their 50 acre parcel that included the property that Luna Park leased. The newspapers announced that Frank W. Bailey of the Title Guarantee Company purchased it for $800,000, but the deal must have fallen through. Six days later George Kessler, head of a syndicate, purchased the company's stock for $1,000,000. It was rumored that ex-Senator Reynolds, head of Dreamland, was involved. Thompson and Dundy claimed that they weren't worried since their 21 year lease had 19 years to go. They didn't care who was their landlord.

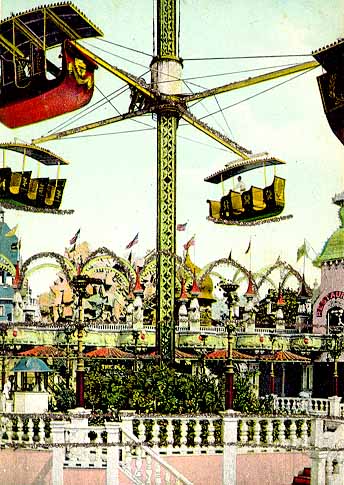

Thompson and Dundy plowed back their profits into additional attractions and a few more acres of sand until eventually they had leased 38 acres. Their changes for the 1904 season were so extensive that parts of Luna were completely transformed. The Venetian city near the entrance along the east side of the Court of Honor was removed and replaced with arcaded walkways topped by a Japanese roof garden. It was a clever solution of both widening the Court of Honor for Luna's increasingly larger crowds, and for providing the visitor with two options for strolling; along the sunny green roof garden decorated with Oriental plants, or beneath through the shaded arcaded walkway that provided shelter if it rained. There was a more open feel seaward of the Electric Tower and room for a variety of small rides like Whirl the Wind, an aerial ride, set adjacent to the Tower, that offered a good high panorama of the park's grounds. Nearby they installed a large new restaurant in the large domed building after Wormwood's Monkey Theater deserted Luna for Dreamland.

Several ride attractions were built in the area behind the Chutes towards the rear of the park. The largest was a L.A. Thompson scenic railway, which was appropriately named Buzzard's Roost for its superb view from the top of its lift hill. Its entrance was in a dome building to the left of the Chutes. The Babbling Brook outdoor water ride was enclosed to become an Old Mill tunnel of love ride. Even Luna's female cashiers, dressed as Mexican senoritas had a new and festive look with their sombrero hats and Bolero red jackets.

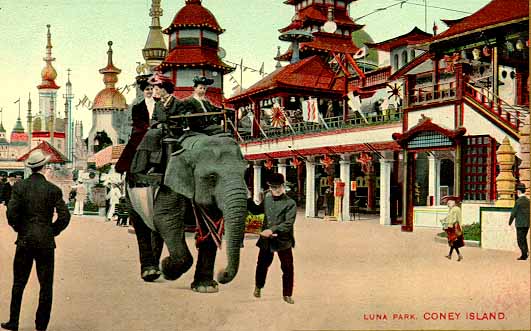

Dundy, who considered elephants a good luck charm after finding the junked remains of one of the Elephant Hotel's front legs when they were clearing the land, became partial to elephant acts. He had four of his elephants slide down a special Shoot-the-Chutes into the water below. Dundy claimed the largest show herd of elephants in the world, and with his forty camels, featured them in a dazzling new production called the Streets of Delhi in a large area of newly acquired acreage. A vice royal palace was built there in miniature.

| The Whirl the Whirl or Aerial Swings. - 1905 |

This spectacular reproduction of the Durbar of Delhi Procession was staged to compete with the shows at the newly opened Dreamland on the seaward side of Surf Avenue. A newspaper reporter described it. "There were gilded chariots and prancing horses, and trained elephants and dancing girls, regiments of soldiers and an astonishing number of real Eastern people and animals in gay and stately trappings. The magnificence of the scene was such as to make those who witnessed it imagine that they were in a genuine Oriental city." Four million park visitors in 1904, 5000 at a time, watched this show. There was a charm about the Streets of Delhi that kept them spellbound. Many returned to watch it a second time. It was an expensive proposition for Thompson and Dundy for it cost them $240,000 to stage it that summer ($68,000 for the animals - mostly elephants and camels). Thompson later admitted that he lost $100,000 on that spectacle, but he felt that it was worth it. Attendance at the park was phenomenal; nearly 4,800,000 paid admissions during the season from May to September.

Another illusion designed and staged by Thompson in 1904 was called Fire and Flames. It had its auditorium arranged that spectators were seated on the other side of the street from a burning four story building. Luna hired hundreds of firemen to fight imaginary flames. A rescue squad arrived to save men and women trapped in the building's top floors, who then jumped to safety into the nets below. Luna was the first park to present a live spectacular show, just barely beating Dreamland's similar show by weeks.

Luna's 1904 aerial circus, staged on three circular raised platforms at the foot of the Shoot-the-Chutes and viewed by 20,000 spectators, included such acts as the Stickney's, bareback, somersault and high school equestrians; Spessardy's bears; Josie Ashton - bareback rider; the Jennetts - equilibrists [balancing act]; Francois, Du Crow and Loranz - breakaway ladder; Bonner, the educated horse; and Dracula, the aerial contortionist.

Zolas, globe and spiral tower act was unusual and only appeared dangerous. A man was concealed inside a hinged four foot diameter metal sphere at the bottom of the tall tower. The sphere was attached to a motorized mechanical arm that rolled the sphere upwards along a narrow spiral track. The man would then pop out of the sphere when it reached the top and surprise the audience.

Thompson and Dundy were forever changing the park's attractions. Their philosophy was that if an attraction failed to pay for itself in a single season, it was scrapped. One of the first casualties for the 1905 season was the 20,000 League Under the Sea show. It was replaced by a small indoor scenic railway called the Dragon's Gorge. Its mammoth archway, illuminated by 10,000 lights at night, was flanked by two enormous dragons, and beneath it for all to see was a huge waterfall set behind train cars plunging in opposite directions. Its tunnels inside featured scenes of the North Pole, Africa, the Grand Canyon and Hades with its River Styx. When it debuted it had the sharpest and steepest curves of any scenic railroad at Coney Island.

The most ambitious of all of Coney Island's spectacles for 1905 was Luna's "Fall of Port Arthur," which depicted the recent Russian-Japanese war. While the two opposing armies bombarded each other over tin hills, 40 miniature battleships, each under their own power and flying the flags of the Tsar and Mikado, cruised around a harbor filled with water and blazed away at each other. The Japanese, upon surprisingly sinking the Russian fleet, trained all their fire power on the town's fortifications until they surrendered.

Luna's main entrance along Surf Avenue was also improved that summer. It was both widened and given an Oriental Turkish look with its crescent moons embossed with the word "Luna" and three pinwheels of red and gold set above the central archway. The Japanese promenade on the left as one walked down Luna Court was moved aside to leave a broad walk to the Electric Tower.

Many new ride sensations were introduced during the 1906 and 1907 seasons. The Double Whirl was the Ferris Wheel taken to the next logical stage. Six small wheels with a seating capacity of 72 people were mounted on a 40 foot diameter rotating turntable. Another and one of Thompson's favorites of his own design, the Helter Skelter was essentially a slide for adults. Participants rode an escalator to the top of a huge chute made of rattan, then they slid down its sinuous course where they landed on a mattress in front of an onlooking crowd. Actually two chutes were set side by side so that couples could slide down together, but the paths split up for a ways before coming together again near the bottom.

| Helter Skelter slide. - 1906 |

Both the Tickler and Elmer Riehl's Virginia Reel were similar rides where passengers rode in rotating saucer shaped cars down an incline plane. However the Tickler's cars mounted on coaster wheels caromed down to the bottom through a maze of posts and rails, while the Virginia Reel's cars rode on tracks past protruding posts that caused them to randomly spin as they serpentined downward into its final whirlpool. The Tickler invented by William Mangels needed large rubber bumping rings to cushion the collisions as its passengers were jostled, jolted and even bounced about in their seats. At the end of the ride passengers were often so hopelessly entangled that attendants had to help them from their seats. When Mangels applied for a concession for his ride in 1906, Thompson looked at his drawings and then in his brusque manner said, "You'll need barrels to take away your money. Come in tomorrow morning for your contract." Luna's standard contract specified that 20% of the gross receipts went to the park. Thompson was right about the Tickler's popularity; 421,000 ten cent admissions were sold in 1907 alone.

| The Tickler - 1907 |

One of its most popular rides, when it debuted in 1906, was the Mountain Torrent. The ride was a combination of a roller coaster and Shoot-the-Chutes. Passengers rode up an escalator or climbed its alpine paths to the top of an eighty foot mountain that featured a series of cascading scenic waterfalls. They would then board tracked cars which raced down and through the mountain in a flume carrying water at 35,000 gallons per minute. The ride ended with a splash in the glacial lake at the bottom.

Theophilus Van Kennel's Witching Waves installed at Luna in 1907 consisted of large oval course with a flexible metal floor. By using a system of reciprocating levers beneath the floor, the ride generated a continuous wave-like motion, followed by another in the flexible floor without the actual floor moving forward. Steerable small cars seating two passengers were propelled forward by the undulating floor. It was fascinating to watch and a popular fun ride.

For the 1906 season as part of Thompson's investment of $500,000 in new rides and attractions, he introduced the Babylonian Hanging Gardens. The covered colonnade on either side of the lagoon was partially removed and converted into open promenades with free seats and boxes. And on the terraces above, where there were also open elevated promenades and picturesque boxes, he added a roof garden with 160,000 plants, many which hung down and added color to the structure. Without increasing the park's acreage, Thompson magically increased the park's capacity by 70,000 and offered protection for his customers in the event of rain.

Luna's Great Train Robbery, an outdoor spectacular show on the world's largest stage, 760 x 170 feet, debuted for the 1906 season. The stage, large enough for a full size locomotive and several passenger coaches, had to be reinforced with 440 extra piles to support the 81 ton load. It occupied the space from the Dragon's Gorge back to Coney Island Creek, the site that had been previously occupied by the old Naval Show and Circle Swing. The show with its cast of 300 people, 40 trained plunging western mustangs, and a real sized steam locomotive with passenger coaches, was run by Arthur Voegtlin. Its entrance through an adobe village lead to seating for 3000 people.

In the first of the 30 minute show's three mountainous scenes, bandits were on the scene as a train approached from the distance at 15 MPH. They stopped the train, and amidst a wild struggle, relieved the passengers of their valuables. Afterwards they escaped to their mountain town hideout, which was fitted out with red-shirted miners and cowboys smoking and drinking in front of rough looking saloons. The attack by a sheriff's posse, that had tracked them there, surprised them. As they struggled to escape amidst the wild shooting, some of their horses shot out from under them plunged them head-first into the streams. The bandits were finally overpowered and captured.

Two other shows featured animals. Mundy's Menagerie, consisting of 200 performing elephants, lions, tigers, etc., held performances in the old Hagenbeck Hippodrome. Another show brought from the London Hippodrome featured trained cormorants commanded by Chinese boatmen in Oriental fishing skiffs. These diving seabirds caught fish out of the lagoon and delivered them to the fishermen.

W.A. Bundy offered a unique concession adjoining the Dragon's Gorge. It offered a railroad trip through Europe in full-sized passenger coaches. It was an illusion skillfully done with via electrical and moving mechanical scenic effects in a space only 65 wide and 100 feet deep.

Luna Park during the 1907 summer season employed 1700 people and had accommodations for the 500 animals used in its acts. Its 1326 spires, towers and minarets were illuminated by 1,300,000 light bulbs. The park consumed more energy than the average American city. It cost $5,600 per week just for the electricity to light the park. In fact Luna had a city's infrastructure and communications network compacted into just 38 acres. It had its own telegraph office, wireless office and local and long distance telephone service.

| The Shoot-the-Chutes ride where passengers in a boat slid down into the lagoon below. - 1907 |

Among the shows introduced during the 1907 season were the Kansas Cyclone, Night and Morning, the Great Shipwreck, and Days of 49'. The later, which replaced the Great Train Robbery, featured the robbery of an overland stagecoach carrying treasure from the California gold mines. Its mountainous background depicted the Sierra's pine and snow capped peaks, red sandstone trails and primitive mountain cabins. The show's roster included miners, cowboys, horsemen, gamblers, Mexicans and Indians. Throughout the show its actors performed, amidst the sound of pistol shots and the crack of rifles, wild riding and horsemanship atop 75 horses and ponies.

The show Night and Morning was Biblical. It offered an audience of 125 the experience of being buried, meandering through Stygian realms and glimpsing hell before being resurrected in the Kingdom of Glory.

The 11 minute show "The Shipwreck" portrayed the capture and sacking of the city of Henlopen, Delaware in 1704 by Captain Kidd's brother. It depicted the town and approach of the pirate ship. By while the pirates looted, a storm arose and drove their unattended ship onto the rocks.

The Kansas Cyclone in a small theater on the east side of the lagoon was much more innovative. It depicted a Kansas town where a traveling circus had set up its tents. Its shops were open and people strolled the streets when an alarm was sounded warning of an approaching cyclone with terrific winds and darkening skies. People screamed and began to run. Clothes blew off lines where they were hung to dry, and as the spiral funnel approached, houses lifted off their foundations. The din was deafening as everything blacked out. When the light returned in a minute or two, the scene was of utter destruction and chaos.

One novel attraction was called the Musical Flower Garden. It was there that visitors were surprised when they stopped to admire the flowers, that they broke out in song. Another, the Molly Coddle, was an elaborate illusion. A large boat inside that held 25 people was set within a triangle of mirrors. The passengers always felt that they would collide with one of the boat reflections. The park's Ostrich Farm near the rear of the park was another novel attraction. Spectators were amused by the huge bird races against bicycles, horses and elephants. And located near the Surf Avenue entrance was a huge new carousel with a menagerie of animals and birds. Included in the $50,000 price was an imported Parisian band organ.

Luna's constant change of attractions brought much repeat business to the park, especially by Coney Island regulars who thought they had experienced everything. By the end of the season paid admissions to the park since its opening in 1903 totaled over 30,000,000. Even Luna's most popular ride, its Trip to the Moon was experienced by an estimated 4,250,000 people over its five year run. Even considering the price drop to ten cents during the final year, the attraction alone earned nearly a million dollars.

Frederic Thompson and Skip Dundy's personalities complemented each other nicely and served as a check on each other. Their partnership operated on the basis of complete trust. Thompson, who was ten years younger than his partner, concentrated on showmanship while Dundy worked on finances. Thompson drank excessively and wasted money. Dundy would gamble on anything and was proud of his female conquests.

When Skip became immersed in one of those card games when $50,000 dollars would ride on a single hand, only Thompson could lure Dundy away on the pretext of a talk about a future attraction. When Dundy found Thompson drunk as a skunk at a Coney Island bar, he would stride in and snatch the glass from his hand and hurl it to pieces against the floor. And when Dundy slipped into a messy love affair, Fred Thompson would offer common-sense advice.

Of course it didn't always work and the winter of 1906-1907 proved disastrous for their partnership. First Thompson married Mabel Taliaferro, an actress on February 29, 1906. Out of blind love, Thompson decided to make his wife a star. He plunged headlong into a new field of dramatic production while neglecting his carnival work and his amusement park. What was more important was that he deprived Skip Dundy of his companionship and advice. Without Thompson, Dundy let his frantic pace run himself ragged. Skip Dundy's sudden and unexpected death, from dilation of the heart and a severe pneumonia attack on February 5, 1907, left Thompson rudderless.

After the public began to lose interest in his Trip to the Moon attraction, Thompson booked the most popular show at the Jamestown Exposition, the Battle of the Merrimac and the Monitor. This cyclorama of the famous Civil War naval battle opened in 1908 in the Trip to the Moon building.

Thompson staged two other shows that season, the Burning of the Prairie Bell and Man Hunt. The latter was a rough riding show featuring 300 men and women, and 125 plunging horses. Its climax was the capture and burning at the stake of a "greaser" (Mexican). The Burning of the Prairie Bell, a much more elaborate show, depicted ante-bellum life on the Mississippi River. Negroes worked in the cotton fields on plantations. Its finale, a disaster, was the burning of a great paddle-wheel steamer.

In 1909 the Crack of Doom show, replacing Man Hunt, portrayed the destruction of a mining village by a mountain torrent that leaped it banks and poured down the mountain side on the defenseless town. Men, women and children, horses and other livestock were swept away amidst the wreckage of homes. It was an expensive show to stage; $200,000. It required a flood of a million gallons of water which was immediately pumped back into a 250,000 cubic foot tank.

After the Battle of the Merrimac and Monitor's two year run, it was replaced in 1910 by Thompson's newest creation, A Trip to Mars by Aeroplane at a cost of $50,000. One hundred passengers were transported in a giant Curtiss type airplane on a trip that began at Governor's Island. The plane, seemingly under its own power, raced Farman and Wright biplanes, before it sailed through the clouds up towards the stars. Enroute it encountered storms and astronautical phenomena as a lecturer on board narrated the sights on the Martian odyssey. It would sail to a port on Mars before returning to Earth by way of the stars.

Thompson also installed a Pneumatic Tube and Miniature Subway ride. Passengers were enclosed for protection as the train wound its way through underground caverns and gorges as it alternately descended and ascended. The Teaser, adjacent to the Electric Tower, was a Mangel's designed ride that often made its passengers dizzy. Its main platform slowly rotated while those seated in linked chairs facing each other, could if they liked, grasp the hub between them and cause their seats to revolve around each other. Other rides included an Airplane Dip and the Lollypop, a water ride.

Thompson always sought out unusual attractions to differentiate Luna from the competition. One attraction, The Human Tarpons, fit the bill perfectly. Patrons equipped with a rod and reel tried to land expert swimmers in a tank. There were three sized swimmers for people of different skill levels, the smallest for children. And Luna was the only park to offer elephant rides. Two elephants Gyp and Judy, were employed to carry 9000 people / week on their backs. One famous guest who rode an elephant on June 25, 1909 was movie idol, Douglas Fairbanks, Sr.

| Elephant rides were popular with both adults and children at Luna Park. - 1907 |

Shows included the Sinking of the Maine, the Monkey Music Hall that featured 50 performing monkeys, the Cabaret Circus, and a magic show called China's Fairy Fountain. The Great Fire Show in 1912 depicted a western town at the height of activity actually destroyed by fire. While fires fascinated the public, the park, too, narrowly escaped a similar fate the previous winter. A fire started in the Pneumatic Subway ride on the afternoon of December 11, 1911. Fortunately low wind and Coney's high pressure water system, that worked for once, kept the blaze from spreading.

Thompson was a spendthrift both at his park and in his private life. In an interview with Everybody's Magazine in September 1908, he estimated that he spent $2,400,000 on Luna since he began building it. His lavish operating expenses, including the cost of rebuilding and installing new shows, were $1,000,000 per year for only a four month season.

His personal living expenses were tremendous and he wasted money like it was from a bottomless barrel. For example, when his schooner Shamrock won the $1000 Lipton Cup during an ocean race to Cape May with Thompson aboard, he rewarded the captain with $38,000, a thousand dollars for each second that he broke the record. His marriage to his wife, who was always on tour in the title role of "Polly of the Circus", finally broke up in 1911. Then when his financial problems became acute, he had to file personal bankruptcy in 1912. Although it was estimated that he was worth $1,500,000 at the zenith of his career, in the end he had $665,000 in debts and little in assets. He lost his beloved Luna Park to his creditors.

On April 3, 1912 Justice Richards of the Brooklyn Municipal Court issued a dispossess order against Luna Park at the request of the Sea Beach Land Company, a major creditor and owner of the land where the park stood. Ironically Thompson claimed that Luna's finances were sound and that it was operating at a profit. However, after the Dreamland fire, their fire insurance was cancelled and it injured the park's credit. With Thompson deeply in personal debt, Luna was left with little operating capital or money to pay creditors. Thompson packed up his things and left the park with the models and plans he had drawn for the 1912 season's shows.

Barron Collier, a former streetcar advertising expert, and his associates took over Luna Park. During the 1912 season they enlarged the park until it had 31 buildings for shows and amusements and 28 rides. New attractions included a Turkey Trot, a gyroscope ride, a Japanese Village, a traveling merry-go-round, a Lolly Pop ride and a Coal Mine attraction where donkeys pulled the customers seated in carts through its dark tunnels. The park employed 1500 employees, had 1,450,000 electric lights, 2054 towers and minarets and used 315 miles of tickets each summer.

Crazy Town in 1913 was the last of the Thompson inspired attractions at Luna. It was a whimsical conception consisting of a collection of room sized or larger children's blocks set at various angles. Each attraction housed inside cost a penny. One called Jack and the Beanstalk was for couples. The girl would sit on a chair while her fellow would pound a dial striker with a mallet. The girl would immediately shoot up thirty feet and it cost her boyfriend another penny and another strike to get her down. In the Bughouse Theater patrons were admitted into a barn where they took an involuntary slide into a haymow. Another was the House That Jack Built, a cage at the top of barber pole, where a bearded lady shaved customers for a penny. The ticket seller was a convict in stripes and was surrounded by barrels of money. Wardens with guns prevented people from robbing the convicts. And to heighten the sense that people were in an unusual place several dozen freaks and albinos mingled with the patrons.

A spectacle called the Fall of Adrianople on a stage 475 x 175 feet replaced the Great Fire Show for the summer 1913 season. A Turkish city with mosques, minarets, castle and a fort armed with 12 inch guns was constructed on stage. During the performance an army of invading Bulgarians, Serbs, Montengrins and Greeks bombarded the town and stormed the fort. The battle raged before an audience of 1800 seated in the grandstand and continued until the garrison surrendered.

Castle's Summer House Dance Hall, backed by famed dancer, Vernon Castle, was erected near the park's entrance in 1914. Captain Lois Sorcho moved his show, Great Sea Divers, to Luna that summer. The performance in an 80,000 gallon tank began with a ship floating in a tank. A sudden explosion sunk the ship and Submarine Men, clad in diving suits, descended to the wreck in an attempt to salvage its valuables. Since shipwrecks were in the news, the show Titanic Disaster used miniature models of the Titanic and rescue ship Carpathia to portray the principal events.

For the 1915 summer season, management added attraction at Luna that previously worked. The Oriental Village was located at the far end of the park and featured native workers (Turks, Arabians & Egyptians) plying their metal trades. There were also whirling dervishes, dancing girls, acrobats and magicians. Camels and cafes serving Turkish coffee added to the atmosphere. The Village of Midgets, elsewhere in the park, was for children. Like Dreamland's earlier version, houses and shops were in miniature. Chefs cooked for the little people while farmers, merchants and performers worked at their various occupations. There was also a tiny theater and the villages animals were miniature.

A Trip to Niagara, located in a big building to the left of the entrance, was novel. Its entrance was a realistic reproduction in miniature of the approach to the suspension bridge at the Falls. Inside one was whisked on a little train above the Falls and then back to the park, a reproduction of Clifton Park in Canada. Patrons could sit among the greenery and watch the play of lights on the huge waterfall.

Management ran the park along familiar lines, but they weren't innovators. First the automobile, then the movies began to date the park's early amusements, and these new owners had no new formula to keep the park competitive or successful. While the park drew millions of visitors each season, it earned much less money than expected.

A few seasons passed with little innovation before general Manager, Oscar C. Jurney, in 1917 added an unusual attraction called the Scenic Spiral Wheel, better known as The Top. It was a 45 ton, 70 foot diameter steel wheel that was tipped towards its heavier side where it rested on its bottom edge. Roller coaster track spiraled around its outer rim from its top to its bottom. As the four car train circled the rim of the wheel, its weight changed the wheel's tilt so that the entire rig gyrated around like a top running low on spin. The train slowly spiraled down and covered 3200 feet of track in two and one half minutes. A second train with a separate admission climbed up to the top of the wheel, then descended through a long tunnel. The wheel was more interesting to watch than to ride, and consequently only lasted through the 1921 season.

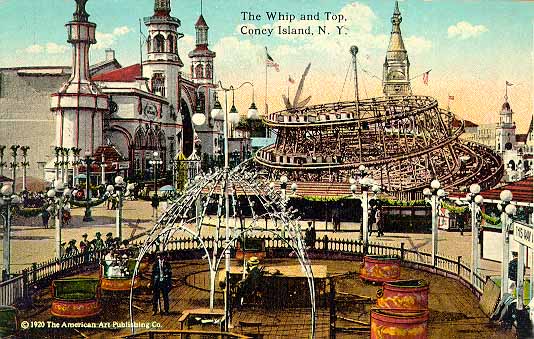

| The Top and Whip rides. |

The First World War was raging in Europe and interest in war-time productions was high once the United States entered the fray. The 1916 production Aerial Night Attacks depicted a miniature German Zeppelin attack on a miniature French town. Small incendiary devices hidden behind fireproof building facades gave the effect of a town aflame. The Zeppelin's movement was along strung cables that couldn't be seen by the audience in the darkened theater. The show was replaced by Submarine Attacks the following season. It too was a mechanical production using miniatures. Another wartime production was Over There. It was a panoramic sensation featuring 150,600 square feet of miniatures. And since German Zeppelins were bombarding Allied cities, aeronaut Frank G. Seyfang's Captive Balloon ride, tethered 200 feet above the park, was attracting the adventurous.

Other attractions installed during the war years from 1916 to 1918 included A Trip to Me-Lo-Die, Darktown Follies, a revue of colored entertainers, an Alligator Farm, and Heppe's Kandy Meat Market where one could buy sweets in the shape of farm animals and pets. New rides included park superintendent Elmer Riehl's Over the Top, a tub ride similar to his Virginia Reel, the Frolic, a circular ride in which the suspended cars swung out, the Tanks, Star ride and Treat-em'-Rough.

Management didn't have a clue what the public wanted or what might be successful so they changed the ride mix continuously. Fun House type attractions was management's guess in 1920. They built a walk in, walk around crazy house called Thru the Falls and a high slide dubbed the Down & Out Slide. A figure eight slide called the Soft Spot was just for kids. Three seasons later management would invest another $100,000 to revamp a fun house into "The Pit." They billed it as "A kaleidoscope of Fun."

Elaborate games had become the rage at Coney Island by the early 1920's. Van Kemp operated his Pig Slide, a skill game rather than a show, although it drew crowds to watch the antics. Customers threw a baseball at a target, which if hit released a pig down a slippery chute. It was quite similar to another game where hitting the target dumped a person sitting on a platform, usually a Negro, into a cold tank of water. Another popular game was Sam Sidi's Kentucky Derby. Customers bet on the outcome of miniature mechanical race horses that moved along tracks at the back of the booth. It was considered a skill game since the players controlled their horse's movement through a mechanical device.

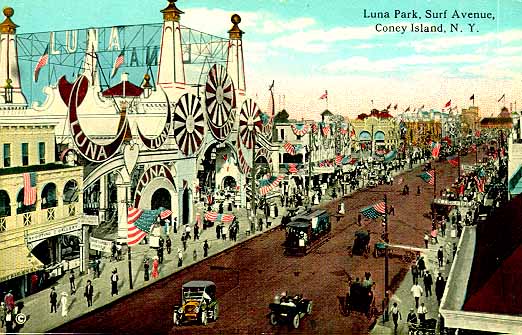

| Luna Park's entrance on Surf Avenue. |

Luna featured a number of shows, some free and some not. China's Fairy Fountains featured magic acts, monkeys were the orchestra at the Monkey Hippodrome, and the Helkvist's, a brother and sister act, dove into a small tank of water set ablaze, Performing animal acts included Mademoiselle Berzac's dancing ponies and Mademoiselle Dolores Vallecita's ferocious leopards.

Barron Collier scored a coup when he convinced Arthur Jarvis to come to work for him in 1924 as Luna's general manager. Jarvis had been instrumental in creating some of Coney Island's most thrilling roller coasters. He built Dreamland's Giant Racer, nearby Brighton Beach's Trip to the Clouds racing coaster and the Bowery's famous Drop the Dips coaster, which he relocated to Luna that winter after the city condemned the property where it stood for street widening. When he built Luna's Mile Sky Chaser that year on three sides of the park, it was Coney Island's highest and longest roller coaster. It featured half a dozen drops, several more than 70 feet. It was immensely popular and had endless lines on weekends. During its first year it carried a million passengers.

In 1925 Jarvis replaced Luna's aging carousel with a new one by the Philadelphia Toboggan Company, bought Custer Cars and a Skooter ride for children yearning to drive. He also bought Traver's newest creation, the Tumblebug which was by far the most interesting of the rides and family oriented. A train of five connected saucers, each holding half a dozen people moved around a circular but undulating track. Passengers held on to the central grip wheel to avoid being knocked into strangers seated next to them.

While Jarvis had a good feel for updating amusement thrill rides with the latest devices from innovative manufacturers, he had little inkling of what other attractions would capture the public's imagination. He regressed to formulas that worked a dozen years earlier by adding natives inhabiting a Samoan Village, and various girlie shows like Hula, Hula Land and the Charleston Girls. He experimented with cycloramas once again, but those like the Battle of the Marne and Little America during the late 1920's and early 1930's failed to capture the public's imagination because motion pictures were more exciting.

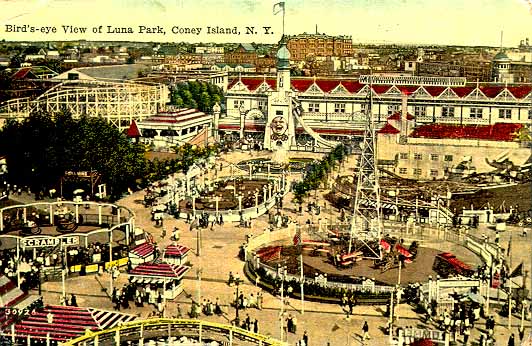

| View of Luna in the late 1920's. Attractions included from left to right in the distance; Trip to the Moon coaster (previously Drop the Dips coaster) and The Pit, a fun house. Other attractions like the Scrambler are in the foreground. |

Roller skating, kiddie rides, marionettes and cockroach racing were tried out at Luna Park during the 1930's without much success. Little money was put back into the park. During the 1930 season they reduced the adult gate admission to 10 cents on week days and 20 cents on weekends. Then they tried the 55 cents combination ticket in 1932, but attendance remained light. During some seasons only a fraction of the lights were lit and the rides were looking shabby and unpainted. The park went bankrupt in May 1933 during the worst of the Depression.

The bankruptcy was a surprise to general manager Rex Billings who was readying the park for its May 27th opening. He had made quite a few changes to the ride mix. He had converted the Fun House building into a skating rink, placed a beer garden in the Willow Grove, replaced the Witching Wave with the Red Bug ride, added ping pong at Sportland, put the Devil dark ride in the space the Jungle Show occupied and installed the 13 Spook Street show where the Hell 'n' Back walk-thru was located. Papa Manteo's marionette show was hired to entertain the kids and the Hurtrel Family would perform in a free high-wire act.

Luna finally opened in the second week of June under receivership. The bankruptcy court decided that since the money had already been spent to refurbish the park for the summer season, the best hope to repay its creditors was to open for the summer season. It rained during its opening weekend and although the weather improved during July and August, the Depression was still on and people didn't have much money to spend on amusements.

Barron Collier remained the owner, but with his considerable business holdings elsewhere, he devoted little time to his park. Once Luna Park was out of bankruptcy in 1934, the Rosenthal Brothers offered to lease the park. Collier considered their offer unacceptable, and instead took a turn at managing Luna himself. It reopened in July with some of the rides open and about half of the park fenced off. After the summer, Collier cut his losses and sold Luna Park.

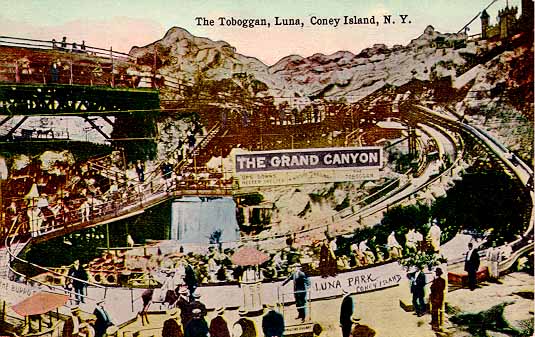

New owners tried the formula again and renovated the park in 1935. The list of attractions included: Shoot-the-Chutes, Dragon Gorge Scenic Railroad, Law and Outlaw, Hu Gard's Mysteries, the Five Presidents, Coal Mine, Grand Canyon Toboggan Railway, Ghost Train, Honeymoon Lane, Aero Trainer, Airplanes, Drive-Your-Own-Plane, Lindy Loop, Circle Swing, Pop-'em-In, Cross the Line, Tilt-a-Whirl, Red Bug, and Leaping Lena. There was also a penny arcade, a vaudeville show in the Willow Grove, a Chinese restaurant named Casino de Marie, two shooting galleries, a Pig Slide, two guess your weight stands, assorted games, bars and refreshment stands. The Luna Park ballroom offered free dancing for adults and also free instruction to children during afternoons.

| The Grand Canyon Toboggan Railway. |

They kept changing the formula and in 1937 tinkered with the park again. each. They added some inexpensive attractions for the 1937 season; a Tumbler ride, a bamboo funhouse, a VooDoo show, and a Mickey Funhouse. An attraction called Daffy Dill & Captain Thompson's Wonder Ship featured a deep-sea monster. Still it was Depression time and the public often came to Coney Island just for its fee sandy beach. They too went bankrupt after only a few years.

During the spring of 1939 prospects that the bankrupt park would open looked grim. Luna had a $400,000 mortgage and the bank was asking $60,000 rental for the park. They figured that it would require an operator $100,000 to open. After Memorial Day weekend was over, the bank reconsidered and on June 12th they leased it to Harry Meinch. The rumor was that he leased Luna for only $6000. Meinch's employees quickly painted the attractions and overhauled them in time for a June 24th summer opening.

Another syndicate of owners led by Milton Sheen in 1940 obtained a 21 year lease on the Luna property and renovated the park for $100,000. The new management tore down several of the beloved older attractions and put in new concessions. One was a tank in which daredevils fought sharks. The manager proclaimed, "people want blood for ten cents." It was the first time in six years that the entire park was open to the public, and with a free gate.

After the two year World's Fair ended and Luna Park acquired a number of exhibits, rides and shows from its midway, Parks Commissioner Robert Moses allowed the park to bill itself as the New York World's Fair of 1941. They offered a free gate and a combo ticket of 17 rides, of which six were new, for 35 cents. William Miller managed the park as an associate with new owners Edward and Harry Lee Danzinger.

They placed the new water scooter near the park's Surf Avenue entrance, and scattered various other new rides and attractions like the Caterpillar, Dangler, Mirror Maze, Lone Ranger, Roll-o-plane, and Lindy Loop throughout the park. Dr. Clooney returned with his Baby Incubator exhibit which was now housed in an eight room house near the Dragon Gorge. Coca Cola rented the huge tower for $25,000. The park boasted that they had $9,000,000 in new attractions and their total investment was $25,000,000.

Half a dozen new shows debuted at Luna that summer, some successful and some not. Aquagirls performed underwater skits in a huge 20,000 gallon glass tank 10 foot wide, 40 feet long and six feet deep. The show provided seating for 400 people at 15 cents admission. Stars on the Ice, on the other hand, charged a steep 44 cents and lasted only one performance on May 30th. Some racy girlie shows like Have You Seen Stella? and East Side, West Side were closed after only a few weeks when License Commissioner Paul Moss considered them immoral.

War time regulations beginning in 1942 curtailed much of the gaiety at Coney Island's parks. They were allowed to remain open for public morale, but dim-out regulations required that the lighting couldn't be seen by overhead enemy planes or by off-shore submarines. Night illumination was with soft blue and dark purple lamps. Where Luna once stood for light, it was now dark and dreary. However, one reporter described it as having the air of a country fair illuminated by Japanese lanterns. New attractions, and even building material for repairs were difficult to obtain.

In the spring of 1944, a fire partially destroyed the L.A. Thompson Scenic Railway (roller coaster) prior to the park's opening. Luckily rain soaked roofs and a windless day checked the spread of the flames. Damages were set at $75,000 for the coaster and the Tunnel of Love ride located beneath. The owners rebuilt the 1901 vintage ride since it grossed $80,000 annually. It opened on August 5th, barely a week before the park was devastated by a major fire.

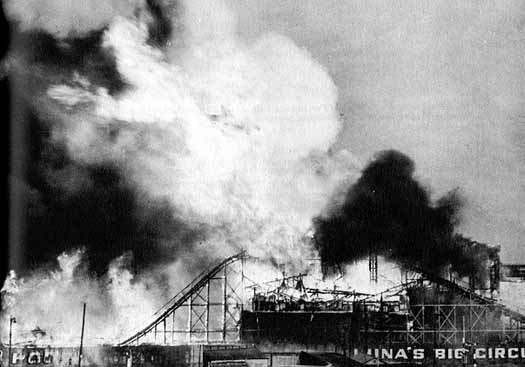

At 3:30 P.M. on August 12th a fire broke out in the washroom at Luna's Dragon Gorge Scenic Railroad building, Luna's other classic roller coaster located midway along the western side of the park. Flames spread quickly to a double row of wooden structures adjoining it, and fanned by a sea breeze raced towards the rear of the park. Fortunately few people were in the park as the fire became so intense that the water in the lagoon began to steam. The Shoot-the-Chutes ride caught fire and the Luna's signature 125 foot tall Coca Cola tower, built in 1903, collapsed in the blaze. Fifty firemen and policemen battling the blaze near the lagoon had to dodge the tower's sudden fall. The owners of the Anderson Dog and Pony Circus quickly evacuated the animals to safety before the arena caught fire. The three alarm fire was brought under control within a few hours, but nearly the entire west side and rear of the park had been destroyed. Luckily the elevated subway line that cut through the park's rear was not damaged. However, sparks blown nearly a half mile away to the BMT Depot caused another fire that destroyed twenty outmoded subway cars.

| Luna Park burned in a spectacular fire on August 12, 1944. |

Damages exceeded a half million dollars and 35 people, one third firemen were injured and burned. The attractions totally destroyed were the Dragon Gorge, Boomerang, Hell 'n' back, Harum Scarum, Spook Street, Tilt-a-whirl, Dodge-em, the Opera House that showed anti Nazi war propaganda films, the Coca Cola tower, and the arenas were the Aqua Circus and the Anderson Dog and Pony Circus performed. Rides that were damaged but repairable were the Mile Sky Chase (coaster), and the Shoot-the-Chutes.

There was $400,000 in insurance but the owners feared that Farmer's Bank & Trust Company, that held a $600,000 mortgage on the park, would claim the money. Besides it was hard to rebuild with restrictions on building materials during World War II.

Since the east side and front of the park along Surf Avenue were undamaged, Luna reopened for the last four weeks of the season. They roped off the damaged area and charged spectators ten cents to see the ruins. Six small rides were in operation but business in the park and at the undamaged ballroom was light.

Luna Park didn't reopen in 1945 while the owners and mortgage holder fought in court for the rights of the insurance money. In September 1946 the bank sold the property for $275,000 to non show business people. Their intention was to raze the site and build a housing project.

On October 5th, while wreckers were preparing the site for the new housing project, sparks from a worker's blow torch ignited a pile of garbage under the roller coaster. The four alarm fire which lasted from 2 P.M. until midnight burned everything except the ballroom, pool and administration building. The later was used for storage until it too burned in a fire on May 15, 1949. The land became a parking lot and then the site for a low income housing development.