Jeffrey Stanton - Biography

It was a time when children were to be seen and not heard. If there was a family affair with relatives, children ate at a separate table away from the adults. When my parents had company in the living room and I came in from playing outside, I was expected to politely say hello, then disappear to my bedroom or the basement playroom which was equipped with a ping pong table.

My family's home was near the East Liberty section of Pittsburgh, although we lived two miles away from the business district in a hilly area. There were no stores nearby, but it was at a time when the milk man delivered milk and a traveling grocery store inside a school bus made the rounds of the neighborhoods to serve housewives who rarely worked. As children. we waited each afternoon for the ice cream truck that sold popsicles and ice cream bars for six cents. This was the age of the nickel candy bar, penny lick-a-maid and penny bubble gum with a baseball card inside. My time was spent reading alone, or with neighborhood children flipping early 50's baseball cards (a skillful form of gambling). It was always safe to play outside, even at night as there were never any strangers in the neighborhood. June was my favorite month because you could catch lightning bugs and squish them on your finger tips to make glowing lights.

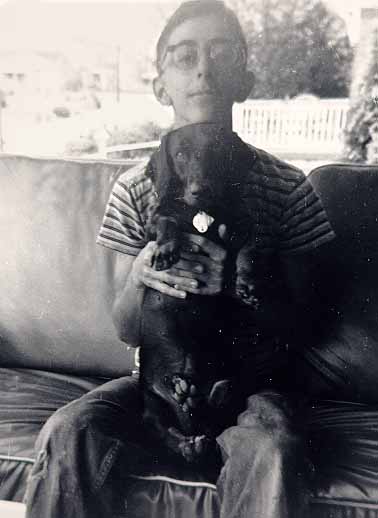

I wasn't a very popular kid but did have one close and loyal friend from aged five to ten. After Skipper moved away I played with the younger neighborhood children whenever they would accept me. Since I wasn't liked much, I spend much of my time with my dog, a dachshund named Dasher. Some folks assumed that I named him after one of Santa's reindeers, but I was just eleven and the puppy was dashing all over the yard, so the name popped in my head.

My grandfather on my mother's side (her parents were divorced) owned a traveling carnival complete with Ferris Wheel, Roll-o-plane, game booths and a few kiddie rides. My parents would take us to see it when it was set up nearby. I had a fear of heights and wouldn't ride the rides. When they did take me on the Ferris Wheel at the age of five, I screamed as we went up until my grandfather reversed it to take me off. I might have gone to work for him as a teenager, but my grandfather retired when I was fourteen, the same year I was brave enough to ride my first roller coaster. It was the Jack Rabbit at Kennywood Park near Pittsburgh.

I'm not sure where my fear of heights and water were rooted, but my dad's medieval methods of handling it certainly didn't help. He would often, while crossing a bridge by foot, lean me over the rail while holding on to my waist and claim that it would help rid my fears. Then when I was ten while on vacation at a Canadian lake, he took my life jacket off and tossed me off the dock. I sunk and had to be rescued from the bottom of the lake. They couldn't get me near water after that.

| Cub Scout Pack 21. Jeff at the age of 10 is the tall boy in uniform on the right in the back row. |

I belonged to the Cub Scouts then graduated to the Boy Scouts. But the requirement to be able to get a First Class badge was the ability to swim. I refused to go to Boy Scout Camp to pass the test and quit. My parents finally solved my inability to swim at age 13 by taking my sister and I to a far away YMCA to be taught by an instructor who was famous for riding kids of their fear of water. I swam like a fish after those lessons.

They fitted me for glasses when I was eleven. My dad discovered that I needed a pair of binoculars to read the baseball scoreboard at Forbes Field where the Pirates played. While I never realized that my eyes weren't up to par (20/200), I was completely amazed when I wore my glasses home the first day. I discovered that trees had individual leaves and weren't just a blurry mass of green.

I wasn't very good in sports and my father was too preoccupied with making money to find time to help me improve. However, I did play Little League baseball one summer when I was twelve. It was a disaster because my domineering father made me play left-handed that year since I was a left-hander who threw wild with my right, my stronger arm. It was always easier for me to bat left-handed because I was left-eyed. My family didn't attend games since it interfered with outings on my dad's power boat that was docked on the Allegheny River.

| Jeff with his dog Dasher. The glasses gave him a nerd look at age 12. |

When I was a teenager my dad bought a 27 foot cabin cruiser while on vacation in Ocean City, Maryland. Eventually I found boating boring because there were never any children to play with, so my sister and I convinced my mother to join a swim club in the suburbs. We spent summer days there where I competed on the club's swim team. My dad eventually sold the boat.

As a child I was always fascinated by mechanical contraptions. I had an erector set that had enough parts to built the large Ferris Wheel. My Lionel train was set up on two 4 x 8 foot plywood panels in the basement playroom. As I got older and my interest changed towards science, I had a microscope and chemistry set. I belonged to a mostly adult astronomy club at Buhl Planetarium and at 12 worked and saved for nearly two years to buy a $200 refractor telescope. Nearly half was earned by operating a store in my garage that sold candy and ice cream to neighborhood children, I bought my inventory from a wholesale house and made a two cent profit on each nickel candy bar.

I was also fascinated by dinosaurs. Whenever I was in the Oakland section of Pittsburgh, I would visit the Carnegie Museum and gaze for an hour at the world class collection of skeletons dug up in Wyoming at the turn of the century. However, the study of dinosaurs in the 50's was dull and boring, and thus I had no desire to be a paleontologist.

I had other hobbies, too, as I collected stamps first and then United States coins. It was easy to obtain unsearched through coins since my dad owned a vending machine business. I often searched for rare dates through $200 bags of pennies and nickels and $500 bags of dimes. By sixteen I was buying and selling coins at local coin shows.

I was also interested in rockets and had an electrically operated launch pad in my parent's driveway. The neighbor's weren't very happy with the arrangement as many of my thin walled aluminum tube rockets blew up and rocked the neighborhood. My choice of rocket fuel was the problem as burning sugar with potassium chlorate isn't always a stable mixture. The oxidizer was readily available in Chemistry class and the teacher once gave me an entire bottle.

Unfortunately as a child I had no mentors. Adults, except for a few high school teachers, had no interest in me or what I was doing. My parents didn't teach me things since my dad seemed to believe you learned things by osmosis. He believed that when you needed to know something, somehow you would just know it. When I asked my parents a question beginning with "Why?' they would retort "Y is a crooked letter." I learned to look things up in books. When I wanted to learn to play chess, I looked up the rules in Hoyle's Rules of Games. Fortunately I became self reliant because I needed to accomplish things with no encouragement.

I attended Peabody High School where I got beat up nearly every week. I was a tall thin nerdy kid, wore glasses and probably weighed 100 pounds at most. Occasionally I ended up in the principal's office because I usually fought back, but lost. I was smart and took most of the advanced classes. By 10th grade I wanted to become a physicist so I took courses in Physics, two years of Chemistry and four years of math. Although I liked art, I was pushed into taking four years of mechanical drawing as my only elective. Getting into a good college was the goal. With high SAT scores in Math and Science along with good grades, I applied to four engineering / science colleges and was accepted to my first choice, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York. Best of all, it was 500 miles away from my parents.

College was considerably harder than high school, especially since most of the students were in the top 10% of their high school classes. As a Physics major, I took Calculus, Physics, Chemistry, German and an English reading class. I lived in the dorm and studied six hours a night, two on German alone. The school was big on ice hockey and as a freshmen you could skate at the rink during gym class. Sophomore year you could play ice hockey in class, and I after my junior year began playing right defense on an intramural ice hockey team at night.

Physics began to bore me during my sophomore year, since I couldn't care less if the atoms spiraled inward or outward. I switched majors to mechanical engineering for my junior year. Since I was determined to graduate on time, I doubled up on my engineering classes and took both my junior courses with their sophomore prerequisites. I got a job that summer with Westinghouse Electric's circuit breaker division to earn money to buy a car and support my snow skiing passion in nearby Vermont. Day passes in Vermont were only $7 and if you showed your college I.D. you could ski afternoons at Brodie Mountain in the Massachusetts Berkshires for only $2.

I received my engineering degree on time and went on to graduate school there where I earned by Masters in Science, Mechanical Engineering. Since I wanted to design industrial robots, which was in its infancy, I took courses in both mechanical design and control systems in the electrical engineering department. Some of my assignments required computer time on the school's IBM mainframe computer. It was the days of punch cards and two day turn-a-round just to see if you made a mistake in programming. It could take weeks to get your program running correctly. We got faster and better results on one of the engineering department's many portable analog computers that we used to simulate the control system for the Saturn V rocket. But that required hours of intricate wiring of the computer's amplifiers and capacitors. The results were plotted on a chart recorder.

In 1969 I moved to Long Beach, California to satisfy the requirements of my draft board that I design weapons in exchange for not fighting in the Vietnam War. I designed airplane control systems for McDonnell Douglas, then Minuteman missiles for TRW Systems.

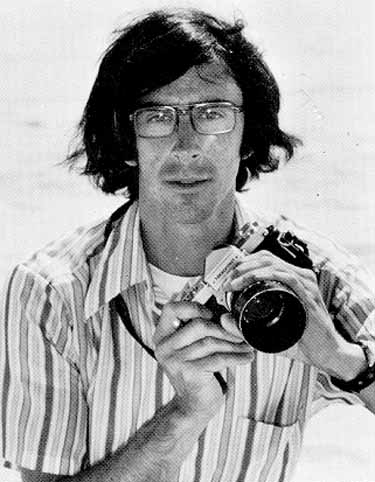

During a two year unemployment period, beginning in 1970, I became interested in still photography. I had been making travel and ski movies with a movie camera equipped with a Cinemascope lens, but it had become too expensive for me and wasn't leading to a career. Instead I wanted to produce a color photo-essay book about Southern California's beach towns from San Diego north to Santa Barbara. The five year project resulted in a book published in 1975 called "Summer is Forever."

I was a terrible writer in college, but fortunately I learned to write during the two year period of writing five drafts for my Summer is Forever book from 1973 to 1975. At that time I had just wanted to collaborate with a writer, but everyone I knew was certain that my book would never be published.

I returned to my aerospace engineering career in 1972 at Lear Siegler in Santa Monica. This required me to relocate and I found an apartment with pool in Venice, California, one block from the beach. When I was laid off once again, I found another job in 1973 at Hughes Aircraft in Culver City. Two years later I was unemployed again and it looked like being out of work during another severe aerospace downturn at least 18 months.

I decided to pursue a full time career as a professional still photographer. Although I had a fine portfolio from my travels around the United States and Europe, I soon discovered talent wasn't the key to success. Photographers obtained jobs in Southern California because they had friends, not because they were good. I never enjoyed parties nor making friends. My photographs, however, were occasionally published in travel magazines, but I wasn't earning enough money to live on. I became manager of my apartment building to balance the budget.

Frankly I had too much spare time. When the neighborhood children built a fort and dock for their rafts on an island on the canals along the Marina Peninsula, I built a bridge to the island with discarded lumber. Then I became more ambitious during spring 1977 and announced to my neighbors that I would build a 50 foot span across the canal at Hurricane Street. It would be the only bridge along a mile and a quarter stretch since the city had condemned and boarded up the Lighthouse and Outrigger bridges. I showed them the engineering plans for a three foot wide foot bridge on two abandoned concrete pilings, then asked for donations to buy 18 foot long wood beams.

The bridge was built over a single weekend with the help of three teenagers and their fleet of rafts. Two days later the city discovered it and condemned it as unsafe when it didn't meet bridge code. The bridge's fate made the news and consequently the city needed a coastal permit to tear it down. A compromise was reached in which they agreed to restore the Lighthouse Bridge in exchange for tearing my bridge down. The city claimed it cost them $7000 (includes engineering and administrative costs) to tear down my $100 bridge, and another $60,000 to fix the other bridge. Only two of the commission's nine members voted to send me to jail.

I became interested in Venice, California's history in 1978. I had heard that the town originally had numerous canals and several amusement piers with roller coasters. I began collecting historic photos and researching the town's past. I had learned to do original source research in a college American diplomatic history course during my senior year. I published a small, thin 60 page illustrated book, a history of Venice from 1905 to 1930. When it didn't sell in the book stores, I sold the $3.95 book door to door during the three months before Christmas. I became very discouraged after that and by 1982, I became a history burnout.

Sometimes I think my passion for creating and collecting illustrated books is rooted in my childhood. While I was a compulsive reader (I'll read the cereal box on the kitchen table), I owned few books as a child until 8th grade. My parents weren't readers except for newspapers and Life magazine. A relative gave me my first book, a child's Lone Ranger when my tonsils were removed at age eight. Then in the 8th grade the teacher introduced us to the Teenage Book Club where I bought classics and boy's books for 25 cents. I also owned a children's set of encyclopedias which I read from cover to cover. I didn't own an art book until I was a senior in college and didn't begin building a small library until I was an engineer. By then I was mostly shopping at used book stores between jobs.

In 1979, when the popularity of Venice's boardwalk reached critical mass and it became a tourist destination, I decided to start a postcard company to promote my photography. I thought it would be simple since no other postcard company made Venice cards nor sold them on the boardwalk. I found a few stores to sell them and set up a tricycle to sell them myself in the middle of Ocean Front Walk. Although I didn't sell many postcards, I held a monopoly on Venice's card business for five years. Customers always claimed that they could buy better postcards elsewhere, but after my competitors came to town, business improved because they could see that my competition had few Venice scenes, which was my specialty.

| Jeff became a free lance photographer after he quit his engineering job. This photo was taken for his Summer is Forever book jacket in 1974. |

The cartoon tourist map business that I began in 1979 was expected to make the real money for my company. I was the first to draw a color cartoon map of a community, similar to ones drawn for amusement parks. It was a poster with advertising on the back, along with lists and locations of Venice's murals and historic sights. The advertising revenue allowed the fold-up map to be sold for only one dollar. While it was a success, I failed to obtain advertisements for adjacent communities. Businesses and Chamber of Commerce people preferred to work with known PR agencies. But the cartoon map concept caught on and others imitated my work and became successful.

I did manage to update the map in 1985, but it quickly turned into a fiasco when the Venice Chamber of Commerce banned the map and television coverage made me a celebrity. Another artist and I became carried away while drawing the cartoons that depicted a gang fight in the ghetto, a mugging, prostitution and drug dealing. While it was true, parts of the community didn't see it as a joke, and when they threatened the stores, it was only available at my postcard stand.

I was unconcerned with my lack of success because I was engrossed with my Apple II home computer. I welcomed my spare time during the slow winter season to be able to design computer games and write software review books for a South Bay computer software company. Eventually I wrote two textbooks on assembly language arcade game programming for the Apple II and Atari 800 computers. I became a computer game consultant and ran my postcard company as a hobby.

As new computers debuted, I upgraded. My favorite computer and the one I type my books on is an Amiga 1200. I wrote the DOS book for the first model in 1985, when it became the first multi-media computer complete with a windowed, multi-tasking operating system. Since it played games exceptionally well, it was considered an expensive toy by Mac and PC business users. Yet it could, back then, run circles around those computers.

Unfortunately I was a generation older than most of the programmers, old enough to be their fathers. I was forcibly retired from the computer game business when I was in my mid 40's. I had been successful in the early days of the home computer business because I people hired me because I was smart. In time, when business and marketing people took over from the nerds, it became like any other business in that getting a job depended on who you knew. Likely there was also resentment towards me in the computer game business since I had given B and C grades, sometimes even a D to many company's software products and lost them money in sales.

Luckily I had resisted pressure from my computer employers to sell my postcard business and therefore I still had a business to rely on. However, I found the postcard business boring and disappointing because I thought that the exposure of my photographs would bring me an occasional photographic job. During the 17 years that I've owned the company, I never got even a single one hour job as a photographer. I get constant praise for my work, but people tell me that they would rather hire their friends, even if they aren't as good. (Note: The photos illustrating my 1996 Venice map are my photographic post cards.)

It seemed that the key to success in the arts was having an outgoing personality to make friends. I didn't have that trait and when I went to a party I managed to meet the five people out of fifty that I had absolutely nothing in common. Besides most adults found my interests juvenile and criticized my lack of motivation in not using my time to make money. Their maxim was "time is money" and if you can't help me make money why would I waste time on you.

Surprisingly it was the neighborhood children and teens in the computer clubs from 1979 to 1988 that found me the most fascinating. After all many felt that I held the perfect part-time job. While I was editor-in-chief of The Book Company (subsidiary of Arrays, Inc.) I got to review all of the computer games that were produced for the Apple II, Atari 800, Commodore 64 and Amiga 1000 computers. I had so many games that I used neighborhood kids to reach the upper levels of the arcade games.

And when I turned my entire living room / dining room area in the early 80's into one huge Lionel train layout (140 feet of track), complete with a full blown operating freight yard and remote firing Minuteman missile cars, the kids were enthralled. My neighbors looked on in dismay at an "adult child." When I wanted to go to the amusement park to ride roller coasters, or go snow skiing in the middle of the week, it was the teens who often accompanied me. Eventually these kids grew up and got jobs and no longer had anything in common with me. I was always hurt that they wouldn't accept me as their friend after they grew up, but I was just part of their childhood, something that they preferred to leave far behind.

With too much time on my hands, I decided to rewrite and expand my original Venice history book; to bring it up to the present and expand the material on its amusement pier history. Venice's long time residents weren't helpful and all photo collections in the community were unavailable for my use. I guess that people resented the fact that an outsider choose to write the community's history.

Publishers weren't receptive either, so when I couldn't find a publisher, I decided to publish it myself. The first version of the book, published in 1987, was 176 pages and had about 200 historic photos. When it was time to reprint in 1993, I did two additional years of research and expanded the book to 232 pages with 90 additional photographs. My experience as a photographer enabled me to choose the very best in historic photos and insist they be printed as clear as the originals, many from 8 x 10 negatives.

Once my book was done I became bored again. When people tried to get me to put my archive on a CD ROM for sale, my eyes rolled. Others tried to get me on the WEB, but I had little interest. Finally a UCLA economics professor, who lives in Venice, made me a deal that was hard to pass up. He offered to have graduate students code my site and was confident that local companies would fund the project. When they declined, the project sat in limbo for months. Finally Don Westland, who designs Internet sites for a living offered me use of his Venice Ocean Front office. I write the material on my Amiga, move it to an IBM disk and code the HTML by hand on his Pentium. I digitize the photos on an HP color scanner, then move it through the Internet to UCLA's Sun work station server at the NAID center.

Of course I'm not making any money designing WEB sites. I've always preferred working on projects that are interesting than ones that pay well. It is likely that if someone offered me $25 / hour to design an uninteresting site, I might decline.

I still set up a table and huge display of Venice historic photos on weekends. Although I rarely sell books (postcards sell OK), I primarily do it to pretend I have a job; besides it brings structure into my life. But people are dismayed that other than my weekend exposure to people, which I find a torture, that I choose to play recluse during the week. I'm used to being alone and it gives me time to read and watch movies. That is just the way I choose to cope with life.

Return to Home Page