Coney Island - Food & Dining

Era of the Clam

During the late 19th century the clam was the most popular delicacy on Coney Island. They were always fresh and plentiful, easily raked up from the shores of Sheepshead Bay and even from the ocean beach. They were served everywhere, tasted good and were cheap. Clambakes and clam roasts were the staple of every picnic and outing. Visitors to Coney Island from the 1870's on could eat grilled clams, sleek with butter, for a penny apiece at Lucy Vanderveer's restaurant. Those that rented bathing suits for twenty-five cents at Tilyou's Surf House, received a bowl of hot clam chowder free. The big luxury hotels like the Manhattan Beach, Oriental and Brighton Beach served clams in their huge restaurants. So did the restaurants like Villepigue's, Tappan's and Lundy's that the rich frequented after a day at the race track.Feltman's & the Hot Dog

In 1867 Charles Feltman owned a pie-wagon that delivered his freshly baked pies to the inns and lager-beer saloons that lined Coney Island's beaches. His clients also wanted hot sandwiches to serve to their customers. But his wagon was small and he knew that it would be hard to manage making a variety of sandwiches in a confined space. He thought that perhaps something simple like a hot sausage served on a roll might be the solution. He presented his problem to Donovan, the wheel-wright on East New York and Howard Street in Brooklyn, who had built his pie-wagon. The man saw no problem in building a tin-lined chest to keep the rolls fresh and rigging a small charcoal stove inside to boil sausages.When the wheel-wright finished the installation they fired up the stove for a test run. Donovan thought that the sausage sandwich was a strange idea but he was willing to try it as Feltman boiled the succulent pork sausage and placed between a roll. The wheel-wright tasted the it and liked it. Thus the hot-dog was born.

In 1871 Feltman subleased a tiny plot of land on one of the big shore lots. He served hot dogs to 3,684 patrons that first season. After a few summer seasons he was successful enough to buy his own shore lot at West 10th Street from Surf Avenue to the beach where he built his Ocean Pavilion. In 1874 he paid $7500 for the restaurant property.

The hot dog, however, didn't go unchallenged. Rumors abounded that the sausages were made of dog meat and the politicians alleged that they found a rendering plant making sausages for Coney Island out of dead horses. John Y. McKane protested that, "Nobody knows what is inside these sausages." He slapped an excise tax of $200 on every sausage stand. "We can not dictate to a man what he must sell," said the Chief, "but we can make it hard for him to carry on his business."Fortunately for Feltman and others the rumors soon subsided and the food became popular again.

| Feltman's Restaurant along Surf Avenue - 1890's |

As more sand piled up on the beach, his lot grew into a series of restaurants and beer gardens shaded by maple trees. German bands and Tyrolean singers entertained the customers. He installed a Looff carousel in the beer garden in 1880 and a collection of amusements, too. There was even a ballroom for dancing.

During the years when the popularity of the race tracks were at their height (1880's-1900's), patrons knew that Feltman's served good food at reasonable prices. They preferred thick steaks and Bavarian beer. The jockeys, trainers and gamblers became regulars and gathered at a big table beneath a maple tree, specially reserved for them.

Feltman's served 200,000 patrons a year during the 1880's, 370,000 a year during the 1890's, 900,000 during the first decade of the 20th century and more than 2,00,000 a decade later. The endless dining rooms could serve 8,000 customers at a time. Feltman's all time record was serving 100,000 people and 40,000 hot dogs in a single day.

| Feltman's Restaurant - Bavarian Beer Garden - 1890's |

Feltman had seven huge grills scattered about its premises, each grilling hot dogs by the thousands. And by 1921, when the extension of the subway brought millions more to the beach, Feltman's served more than 3,500,000 customers; in 1922 more than 4,100,000 customers and in 1923 more than 5,230,000 customers. The majority, by then, bought hot dogs for ten cents each.

The Depression in the 1930's began the decline of Feltman's business. Visitors to Coney Island could barely afford the subway ride yet alone a sit down meal at Feltman's. In 1946 the Feltman sons decided to sell the family restaurant and fun zone. They sold it to Benno M. Bechold an executive of the Savoy Plaza Hotel for $850,000. He had plans to build an addition to the restaurant facing the Boardwalk.

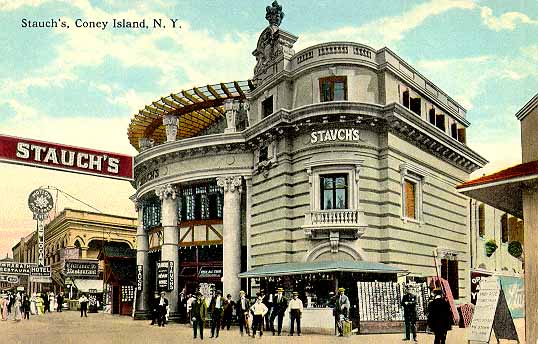

Stauch's

Another Coney Island venerable institution was Stauch's located on the Bowery. It differed from most of the other beach establishments since it was solidly built of brick and stone like it belonged in urban Manhattan. Inside it was comfortable and roomy and attracted an upper class clientele to its dining room and dance hall.Louis Stauch came to Coney Island as a sixteen year old in 1877 where he got a job playing piano in Daniel Welch's saloon. By day he was a dishwasher and potato peeler, and by night he was a waiter, busboy, barkeep and piano player. It was hard work and he was paid only $15 / month. He was frugal, sleeping on the kitchen floor at night, and eating on the premises, but after two years he had saved $310. It was enough to lease Welch's place for $700 a year. He did so well that he renewed the lease for ten year at $2000 / year. When a storm wrecked his first restaurant, he hired McKane to build him a new one 60 x 120 feet.

Stauch was a hard worker, silent and humorless, but a good-hearted little man. He gained a reputation for serving a good, well-cooked meal at a reasonable price. His reputation spread war and wide.

The Bowery burned several times, but each time Louis Stauch rebuilt his restaurant. It became an immense building that at the time housed the biggest dance hall in the world. True or not, three thousand couples could get out on the dance floor and do the Grizzly Bear to Al Ferguson's band. Diners on the balconies above the dance floor could watch. There were other more formal dining rooms, and four bars serving hard liquor and a cigar stand in the lobby that was the equal of anything in Manhattan.

| Stauch's Restaurant and Dance Hall - 1905 |

Stauch's was comfortable, more so than usual because its owner lived there. He ate in his restaurant, was measured for clothes in his restaurant and slept in his restaurant. When he married late in life, he even spent his honeymoon in his restaurant. In a quarter century, he never spent a single night away from Coney despite his friend's attempt to get him out. In fact one day they shanghaied him by train to Atlantic City and checked him into a hotel. But he managed to sneak away and return by train to Coney, where he slept in his restaurant, his record intact.

Prohibition came in the early 1920's. Stauch, who was in his 60's, finally sold his beloved restaurant.

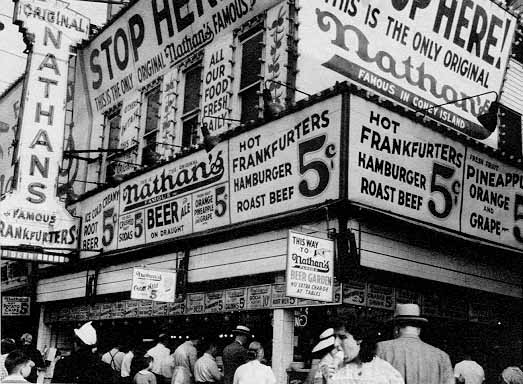

Nathan's

Nathan Handwerker visited Coney Island in the summer of 1915 and saw a help wanted sign at Feltman's restaurant. Although he was a manager of a modest restaurant in downtown Manhattan, he decided to take the job slicing hot dog rolls for a living. Within a year Nathan had saved $300 by frugally eating free hot dogs at Feltman's. It was enough money to rent the ground floor of a building located near the corner of Surf and Stillwell Avenues. He installed counters in the weathered clapboard building and nailed up large red signs proclaiming the five cent hot dog.It was a great idea but Nathan nearly went broke. Even when he offered root beer on the house and threw in a free pickle, the public was suspicious. They ignored him and took their dimes to Feltman's.

Then in the early 1920's the subway extension enabled millions of New York's poor to reach Coney Island for only a nickel. Nathan's stand had a strategic position directly between the subway terminal and the boardwalk. But even they, with only nickels in their pockets, were mistrustful of Nathan's cheap price because in their experience, anything so cheap was inferior.

To draw business Nathan resorted to hiring derelicts to sit at his counter and eat free hot dog. But the crowd saw only bums and avoided the place. Then he borrowed ten white jackets with white pants and ten stethoscopes from a friend in the theatrical costume business and dressed ten freshly shaven bums as doctors. When the public saw his sign, "If doctors eat our hot dogs, you know they're good!", they began patronizing his stand. He became so successful that the police were always trying to clear the mass of customers that blocked the broad sidewalk in front of his stand.

Although his counter was only twenty feet long, Nathan's sold an average of 75,000 frankfurters every summer weekend. His record was on Decoration Day 1954 when 55,000 hot dogs were sold on a single day. Naturally his counter became bigger and Nathan's became a year round operation. On July 6, 1955 he sold his one hundred millionth hot dog.

| Nathan's became the king of the hot dog during Coney's Nickel Empire. |