Coney Island - Early History

(1881 - 1903)

Revised September 15, 1997

One of the wickedest areas of Coney Island, especially in the 1880's and 1890's, was "The Gut", a latter-day Sodom, located between W. 3rd and W. 5th in the approximate center of West Brighton. It was ramshackle groups of wooden shanties and cottages that housed pavilions serving Milwaukee beer, bars, cabarets, fleabag hotels and houses of ill repute (prostitution). As a den of iniquity, it attracted common criminals, prostitutes, and the jockeys, stable boys, touts and others who were employed at Coney's race tracks.

Patrons of businesses there knowingly took their chances in places that were rough, ready and dangerous. While many bars offered cabaret on a raised stage flanked by perpetually open curtains, it was only window dressing to increase the patron's bar tab while watching the free show. Entertainment featured slapstick comedy routines, or a pair of shapely female dancers accompanied by a piano player. Larger places had a larger stage and along the sides and back of the hall were curtained booths where preferred guests might sit and watch the shows. Eight or more chorus girls, dressed in tights and spangles performed a minstrel ensemble. Afterwards the girls would come down into the hall and sit at the tables with the guests.

One of the common methods to separate a man from his money was to employ girl singers and have them hustle tables; meaning sit with customers between performances and jolly them into buying more liquor. These girls, who received a 25% commission of the bar take and often earned $100 per week, ordered liquor but were served only water. Girls, who worked in "houses of poor repute," often pretended they were dancing the can-can and could often get a dollar for a private dance without clothes. A huge bouncer patrolled those "Concert" halls and roughly ejected anyone who violated the loose rules of decorum. Pick pocket and jewelry thieving were common and bloody fights even more numerous.

Larger pavilions with hotel accommodations while not exactly sinful were lively. Duffy's St Nicholas Hotel employed Joe Weber and Lew Fields, two eleven year olds, to do knockout comedy. They had a repertoire ranging from dancing in unison to black face and acrobatic antics. They worked from 10 A.M. to midnight and were paid two dollars a day and five beer checks which they sold to the waiters for fifteen cents. One day a man named Trebor, who ran the pavilion next door, offered the boys three dollars a day and seven beer checks to work for him. The boys accepted without quitting their other job since they figured with lengthy intermissions between shows they could work both places.

Since Duffy and Trebor each thought that they had exclusive rights to the talented youngsters, the deception couldn't last. During their act at Trebor's one Saturday night while they were imitating a pair of East Side women bargaining at a pushcart market, Duffy strode down the aisle brandishing a coach whip in the air. The boys spotted him and fled. They shot through the door, across the sand and into the surf where they waded deeper and deeper, each holding their breath as the surf roared overhead. They nearly drowned from the weight of those wet dresses. Meanwhile Duffy went for Trebor and the resulting fight was a draw. But the men reached an understanding that Weber and Fields worked only for Duffy.

Cheating Gut customers was common. The most common ruse was for the waiter to take a customers five or ten dollar bill and not return the change. When he inquired an hour or so later, both the owner and waiter would deny it and threatened to throw the man out of the bar if he called them liars. The ruse usually worked and the man departed peacefully.

It wasn't unusual for Gut residents to give knockout drops to outsiders either. The usual 'mark' or patsy was a heavy drinker who they slipped a teaspoon of hydrate of chloral in his drink. If someone looked big and powerful or was drinking heavily and might resist the poison, bigger does might work. Sometimes there were mishaps when a man's heart didn't just slow down, but stopped. Of course in those days, without much of a police force, nobody inquired. If the customer was lucky he woke up the following morning minus only his watch and wallet.

McKane, when he acquired his own police force in 1881, cleaned up the worst of the Gut's sins. He made raids in the Gut, took prisoners and chased some bad actors from the island. The rest of the inhabitants got the message and tamed down. The more successful proprietors used their profits to open establishments beyond the Gut's core area, especially after it burned in 1883..

Coney Island's three big luxury hotels, the Manhattan Beach, Oriental and Brighton Beach were the epitome of a gracious and leisurely age, a unique expression of their era. They were long rambling wooden structures, 600 to 800 feet in length with deep verandas (porches) reaching down their entire length. They faced the sea but were set back by wide green lawns decorated with beds of geraniums and lobelias, and had broad curving walks.

| The 700 foot long Manhattan Beach Hotel was built in 1877. It featured 258 lavish rooms, restaurants, ballroom and shops. - 1890 |

They took pride in their cuisine which was served in immense dining rooms where the evening dress was formal. Littleneck clams were twenty-five cents per portion, baked bluefish - forty-five cents, roast lamb with vegetables - sixty cents, and a desert of meringue glacee - thirty cents. Diners would be lucky to avoid spending at least $3.50 for a typical dinner meal; a half week's wages for the ordinary man in 1880.

Evening entertainment included music and fireworks. Bands like John Philip Sousa, and Patrick Gilmore's 22nd Regiment Band entertained with concerts. Young ladies swooned when the celebrated cornetist Jules Levy entertained at Manhattan Beach and Admiral Neuendorf's Naval Band played at Brighton Beach. Those who yearned for something more exciting often attended one of Henry Pain's spectacular firework's displays. These depicted scenic wonders, famous legends and battles. Pain conjured up colorful rocket bursts, bombs and Catherine wheels to depict the defeat of the Spanish fleet at Manila or that of the Russians at Vladivostok.

These gracious hotels became more and more popular as salt water bathing became popular. The Manhattan Beach Bathing Pavilion increased its number of bathhouses from 117 in 1877, to 800 the following year. They doubled their capacity for the 1879 season and in 1880 offered 2,350 single bathhouses and 350 larger rooms for groups of half-dozen bathers.

The exclusive New York City clubs adopted the hotels as their summer headquarters. The Manhattan Beach Hotel was used by the University Club, the Union League Club, the New York Club and the Coney Island Jockey Club. The Brighton Beach Hotel to the west was home to the Bullion Club and the New York Club. The Oriental Hotel, the most snobbish of the lot, served rich customers with their families who often stayed the entire summer. Weekends were the most crowded when passengers arrived on trains seventeen cars long. Cots were set up in the hotel's corridors to accommodate the overflow.

The wealthy and fashionable crowds that frequented the hotels at Manhattan and Brighton Beaches needed diversion and many craved a race track. In those times most men fancied themselves as expert judges of horse flesh. Every Sunday there were hundreds of impromptu races along Ocean Parkway and thousands of spectators crowded around those who were taking bets.

In 1879 William Engeman was the first to meet the public's need when he formed the Brighton Beach Racing Association. It took him only six weeks to build his track and grandstand at Brighton Beach. It's sandy track wasn't very good for setting records when it opened in June 1879. It wasn't the best location either as it sometimes flooded during heavy rains.

The Coney Island Jockey Club, envying Engeman's success and led by August Belmont, Jr., William R. Travers, and A. Wright Sanford, began carving out their Sheepshead Bay track out of a maple and oak forest. When it opened in June 1880, its judges, W.K. Vanderbilt, J.G. Lawrence and J.H. Bradford were well known horsemen. It immediately became a successful race track and attracted wealthy men who thought of it as their playground. Horsemen like Bet-a-Million Gates, James Buchanan (Diamond Jim) Brady (steel salesman), A.J. Cassatt (railroad baron), Jesse Lewisohns and Abe Hummel were regulars and owned racehorses. Brady's colt, Golden Heels was winning every race it entered.

The whole stretch of shore on the north side of Sheepshead Bay was bought up by millionaires. They built docks for their yachts, lodges were they could live and entertain, and stables for their horses. They created three great restaurants; Tappan's, Villepigue's and Lundy's.

The third race track wasn't built until 1886. It was built by the Brooklyn Jockey Club, which included some of the same men who had earlier formed the Coney Island Jockey Club. Noteworthy among them were Phil and Mike Dwyer, prosperous Brooklyn butchers. The track was built at Gravesend, just off Ocean Parkway.

For a time there was talk of opening a fourth race track when Tammany leader Richard Croker considered buying the entire West End of the island. Senator Mike Norton would have sold, but Croker dropped the idea when Austin Corbin declined to extend his Long Island Railroad to the Point.

The three race tracks made Coney Island the race track capital of the country. Their seasons somewhat overlapped so that horse racing fans could find a race from May through October. Each held high stake races. The crowd would start the season in the spring with the Brooklyn Handicap at Gravesend, move on to the Suburban at Brighton, and then to Sheepshead for the Futurity around Labor Day. During its last fifteen years of Coney's horse racing dominance, the Preakness became Gravesend's outstanding annual race.

Coney's three race tracks were essential to the development of Coney Island because they drew to the seaside horse racing fans of all walks of life. The politicians, easy money men, Wall Street barons and Western railroad men, society leaders, actors and actresses, the parasites of the rich and large group of middle class all visited Coney and needed places to sleep, eat and party. Crowds grew yearly and by the 1905 and 1906 racing seasons 40,000 people would be on hand to cheer the winners in the Suburban or Futurity races. While the well-to- do stayed at Manhattan and Brighton Beach's three luxury hotels, professional gamblers thought nothing of spending $20 a day for a room at Richard Ravenhall's hotel and bookmakers made their headquarters on the porch of the Riccadona Hotel, opposite the Brighton Beach Music Hall. Others that profited from the racing crowd were Risenweber's, the Shelborne Hotel, Pabst's Hotel and Dick Garm's hotel in the old Sea Beach Terminal.

Betting was considered the lifeblood of the sport, and while it was considered illegal John Y. McKane turned a blind eye to what was going on. McKane stuck to his philosophy that those who bet knew what they were doing, and that anyway, reforms were up to the Jockey Club officials.

While all three tracks were financially successful, they faced legal challenges by Brooklyn's reformers and its anti-gambling statutes. When preachers complained, Brooklyn's authorities had to act. First Engeman was arrested and indicted in 1885, and again in 1886. Then the governors of the Coney Island Club were served with subpoenas and actually put on trial for permitting gambling at their track. While everyone knew that there were as many as one hundred bookmakers operating at each of the three tracks and each paying management $100 / day for the privilege of handling $15,000,0000 in bets, it was another thing to convince a twelve man jury that betting on horses was a sin and punishable. The odds were always in the favor of the accused since several of the men on the jury were sure to be horse-players themselves.

But it wasn't until 1908 that reformers had any real chance to enact legislation against track betting. When William Randolph Hearst ran for governor that year, one of his campaign issues was the mortal sin of gambling. His opponent Charles Evans Hughes, who eventually won the election, assured voters that if he won gambling wouldn't be an issue. But he immediately double-crossed the voters by calling a special session of the legislature to enact laws against betting of horse races. Again arrests reached a peak, but it was nearly impossible to convict. However, after a two year struggle the horseman finally decided that they had had a enough. Both the Gravesend and Sheepshead Bay tracks closed in 1910, while Brighton Beach had closed three years earlier.

During the 1880's there was plenty of opportunity for those entrepreneurs who could provide diversion for Coney's Island's tourists. In 1885 James V. Lafferty built the Elephant Hotel, a small hotel in the shape of an elephant. It stood 122 feet high, with legs 60 feet in circumference. A cigar store operated out of one front leg, and a diorama was in the other. A spiral staircase in the hind leg led visitors upstairs where a shop and several guest rooms were located. The elephant's head, facing the ocean, offered good vistas of the sea through slits where the eyes were located.

| The Elephant Hotel and Sea Beach Palace to its right were inland of Surf Avenue - 1890's |

In 1882 Peter Tilyou and his twenty year old son George built Coney Island's first theater, the Surf Theater amidst a cluster of clam bars, bathhouses and lager-beer saloons. It would headline vaudeville acts like Pat Rooney, Sam Bernard, and Weber & Fields. To make sure their customers could reach their theater easily, they cut a crude alley located between Surf Avenue and the ocean and paved it with planks. Although they called it Ocean View Walk, the area began to resemble New York's Bowery, an area that was noted for its sin and theatrical bright lights. Mrs. Newton, McKane's chief lieutenant's mother dubbed it the Bowery and the name stuck.

The Bowery developed a reputation of sin and debauchery. There were places of low moral character like the Silver Dollar Saloon, Paddy Shea's St. Dennis Restaurant, Inman's Casino, flea-bag hotels were prostitution flourished, and cheap cabarets like Perry's at the corner of 15th. Eventually other, with more taste, like Louis Stauch, who began work at Daniel Welch's saloon, saved his money and leased his former employer's establishment, offered upscale entertainment and food.

Wine, woman and gambling were the three chief magnets of Coney Island. Many establishments featured "men only shows" where one could gamble on a shell game, monte layout, a roulette spindle or a monty wheel. Every place on the island was a "gyp-joint" and every game had a trick or cheating device called a gouge, squeeze or gimmick.

It was strange that the crowds of the day didn't seem to resent all the fraud. It was more or less expected as part of the adventure. Those that were fleeced one day, inevitably came back to be plucked another day.

When the Bowery burned in 1903, Stauch and others rebuilt in brick and improved their establishments. Paddy Shea called his new place Shea's Grisley House. It soon gained favor among the race track crowd where they could gather afterwards to drink champagne.

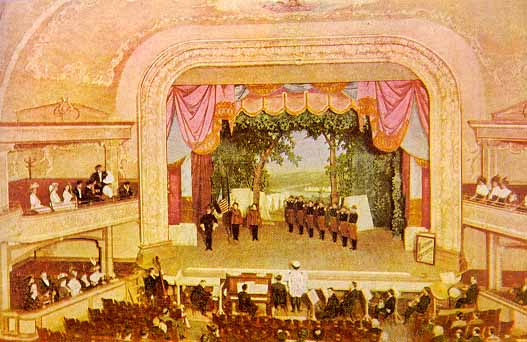

Henderson's Music Hall was another business along the Bowery that began as a restaurant in the late 1880's. Henderson too, replaced his wood frame business with a brick one when it burned, and he added a music hall. Henderson staged vaudeville shows on Broadway's scale but wasn't attracting enough business among the race track crowd. The owner was out West when his son telegraphed that the music hall's comic opera company was doing poorly. His father wired back, "Put in another company." His son misunderstood that his father wanted to cut his losses, and instead added a new troupe to the one already there. While the overhead was double and should have bankrupt them, remarkably Henderson's began playing to packed houses and turned a handsome profit. Their patrons knew an entertainment bargain when they saw one and appreciated extravagance.

| Henderson's Music Hall - 1890's |

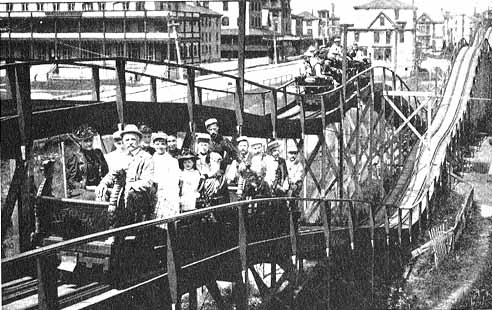

Another entrepreneur became a pioneer of Coney Island's amusement ride business. In 1884 Lamarcus Thompson built the first amusement railroad in the world. His Switchback Railroad at W. 10th Street at Coney Island consisted of a pair of wooden undulating tracks on a structure 600 feet long. A train started at its highest point and ran down grade and up until it lost momentum. Passengers got out while attendants pushed the train over a switch to a somewhat higher point on the second track. The passengers boarded the train again and rode back to the starting point. It only cost Thompson $1600 to build, but his ten cents per ride receipts averaged $600-700 per day.

| Lamarcus Thompson's Switchback Railroad was the world's first roller coaster - 1884 |

Other ride operators and inventors followed. Soon there were additional scenic railways of increasing complexity and thrill. In 1885 Alcoke tied the two ends of the tracks together in his Serpentine Railway and Philip Hinkle's Oval Coaster was the first to use a hoist to pull cars to the top of the first lift hill. Feltman's installed a Flying Boat Coaster on the beach in 1886.

The Tilyou family continued to prosper as their Surf House restaurant and Sea Beach Bathing Pavilion's business grew. Twenty five year old George was a successful real estate broker when in March 1887 he decided to turn state's evidence to the New York State legislature's committee investigating the corrupt administration of Coney Island's police chief, John Y. McKane. Testifying was a dangerous thing for Tilyou to do, but the committee assured him that with enough evidence they could put McKane behind bars. But what they didn't realize was that McKane's political friends, especially Brooklyn Boss, Hugh McLaughlin, could extend his shield and protect him at the state capital. In Albany the committee's findings were simply pigeon-holed.

George's treachery cost him his real estate business and his family was swindled and strong armed out of their lease and property for their seaside businesses. His father, Peter Tilyou fled the island while his mother stayed and with the help of a friend's life savings, managed to retain ownership of the family home. George stayed too to help his mother run the modest Mikado Baths that she had opened nearby.

Tilyou would eventually see his enemy topple. McKane received political protection for his ability to deliver the vote, especially during presidential elections. But to do that he had to commit vast voter fraud and prevent official observers from monitoring the 1893 election. He ruffled too many prominent reform minded Brooklyn citizens and was indicted, found guilty, and sentenced to serve six years at Sing Sing prison for voter tampering and fraud. Crowds lined the street on March 1, 1894 to watch him depart. The resort's most notorious political boss had fallen.

While businessmen like Feltman in West Brighton profited by the build up of sand that increased the depth of their ocean front property, the beach was steadily eroding to the east of them at Brighton Beach. By 1888 the beach became so badly eroded in front of the Brighton Beach Hotel that waves threatened the structure. To save the 500 foot long, three story hotel that weighed 6000 tons, workers jacked up the entire hotel placed it on 120 rail cars, and eased in inland six hundred feet. Six locomotives in two teams of three each, beginning on April 3, 1888, moved the building so gently that not a pane of glass was broken nor a mirror in a room was cracked. The job was finished on June 29th with the hotel ready for business.

Streets of Cairo, which opened in 1897 along Surf Avenue at W. 10th Street, appeared to be an exotic stage set of minaret topped buildings along narrow alleys. Barkers offered camel rides and glimpses of belly dancers of the likes of "Little Egypt." But the area was actually a shrine to the god of chance. Stalls and shillabers brought visitors into contact with the games, and few escaped without losing. Those who refused to play found that they had been victims of pickpockets.

Periodic fires would also be the nemesis of Coney Island. However, they would change Coney Island's character and help modernize some of its seedier sections. The notorious Gut partially burned in 1883 and in 1892, a fire that started at Chamber's Drug Store, burned the West Brighton Hotel. During May 1894 the West End suffered $800,000 damage when burned. Then two years later the Elephant Hotel and the adjacent scenic railway, the Shaw Channel Chute, burned in a spectacular blaze that deprived Coney of a landmark. West Brighton endured another fire in 1899 and in 1903 the Bowery from Steeplechase's entrance to Feltman's was completely consumed in flames. Some felt that fire and brimstone was an appropriate end to the debauchery that occurred there, but owners surprised skeptics and rebuilt.